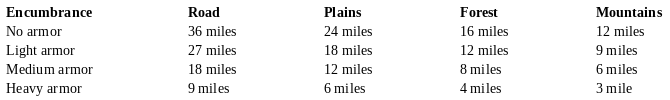

Kaendor is a continent that is very large and very sparsely populated, with almost all land covered in trees or steep mountains. For campaigns in a setting like this, especially when it ‘s intended for parties with numerous followers and animals, tracking food and water supplies and dealing with the consequences of hunger and thirst is something that really should be part of the game and the everyday travel procedures. While B/X provides a neat simple system for hunger and thirst, the rules for hunting are very vague and appear implausibly inefficient.

So here’s my take on it. The foraging system is taken straight from the Expert set, and expanded with the hunting mechanic. With how often players will likely go hunting throughout a full campaign, I really don’t want to bother with having combat encounters with rabbits and deer that might just run away. The mechanic for hunger and thirds is straight from Basic Fantasy, though I added the time limit to die from dehydration regardless of remaining hit points.

Hunger and Thirst

Humanoid characters need one ration worth of food and one waterskin of drink every day. Characters who do not get sufficient amounts of food lose 1 hit point per day. If they don’t get sufficient amounts of water, they lose 1d4 hit points per day. In either case, the characters are unable to naturally heal any damage without magic until they receive enough food and water again. In addition, characters who go without water die after 3 days. Characters with a Constitution score of 13 or higher can survive for an additional number of days equal to their Constitution bonus to hit points.

Foraging and Hunting

In most circumstances, parties come across enough sources of drinkable water in the wilderness to refill all their waterskins to full. So unless the GM specifically states that no water source was encountered during the day, water consumption does not need to be tracked. If the party stays in areas without natural water sources for an entire day or more, one waterskin has to be subtracted every day, but finding any source of drinkable water is usually enough to refill all waterskins to full.

Rations of food have to be tracked every day the party spends outside of settlements. While traveling through the wilderness, characters can gather edible plants they find along the way, and the party has a 1 in 6 chance to collect 1d6 rations worth of food on any given day. In practice, this number is simply subtracted from the number of rations that are consumed on that day. (Assume the characters eat food that is close to perishing first and keep any food that keeps well for later, so there’s no mechanical difference between preserve rations and fresh plants or meat.)

Alternatively, the party can decide to not travel on a given day and instead spread out around the campsite to hunt for food. Each group of hunters has a 1 in 6 chance to collect 1d6 rations worth of food, but also makes separate checks for random encounters at noon. (Random encounters in the morning and evening are assumed to happen at the camp.)

The Essentials Version

Hunger: Characters who do not eat one ration worth of food in a day, suffer 1 hit point of damage and can not heal damage naturally without magic.

Thirst: Characters who do not have one waterskin worth of drink in a day, suffer 1d4 hit point of damage and can not heal damage naturally without magic. After 3 days + 1 day per CON bonus, the characters die.

Foraging: A traveling party has a 1 in 6 chance to find 1d6 rations worth of food per day.

Hunting: A party resting at camp for a day can send out hunting parties that each have a 1 in 6 chance to find 1d6 rations worth of food per day.