As far as I am able to tell, I started working on a concept for a fantasy setting that eventually developed into Kaendor in its current state at least 15 years ago. For most of these years, it’s been my primary hobby and I surely must have spend well over 10,000 hours on it by now. I’ve run five different campaigns in various versions of the world so far, but I always felt like the things that make the world so special to me did not really come through in the adventures that the player’s got to experience. From what I remember, I always fell back on well established, conventional D&D adventure setups, and the players probably did not see much of a difference.

I have come to think that one probable cause of this might be the fact that the mental images that I am dreaming up about Kaendor are not exactly gameable content. What I am seeing when I am thinking about what my perfect fantasy world would be like are primarily stunning environments, but also fantastic creatures and interesting cultures. But what I am not really seeing in my imagination are stories, characters, or events. Amazing lairs for great monsters or villains perhaps, and even really cool setups for exciting fight scenes. But I never really had any success coming up with interesting people, hidden plots, grand designs, or escalating conflicts.

The world that is emerging from my imagination and creativity is one that would be stunning to behold, and perhaps fascinating to read travel guides about. But that’s not exactly gameable content. Not if the kind of gameplay I am interested in is about descending into dark and dangerous places and facing off against strange and terrifying beasts. Gazing out over a magnificent landscape from the porch of your comfortable little hut is not a game or an adventure.

I think if I would ever get bored with this RPG stuff, I would make a much better fantasy painter than a fantasy writer.

However, I’ve been thinking last week that perhaps there could be forms of fun and exciting adventure play that still draw upon those aesthetics and sensibilities that are fueling my imagination. And I was quite surprised by the amount of engagement that my idle thoughts on the subject got on Mastodon. And so here we are, with a more in depth explanation of the general ideas I have been entertaining.

A Campaign Aesthetic

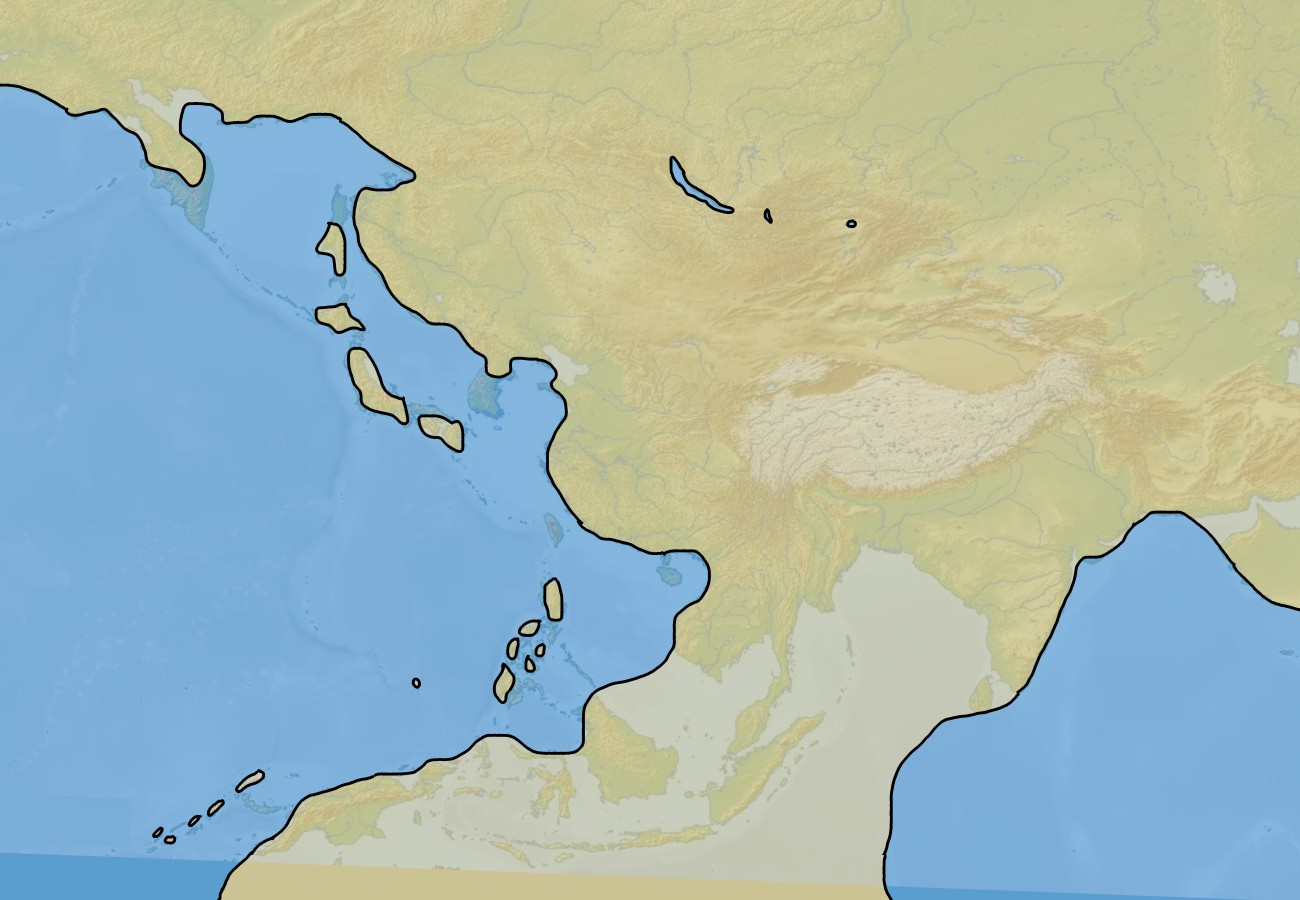

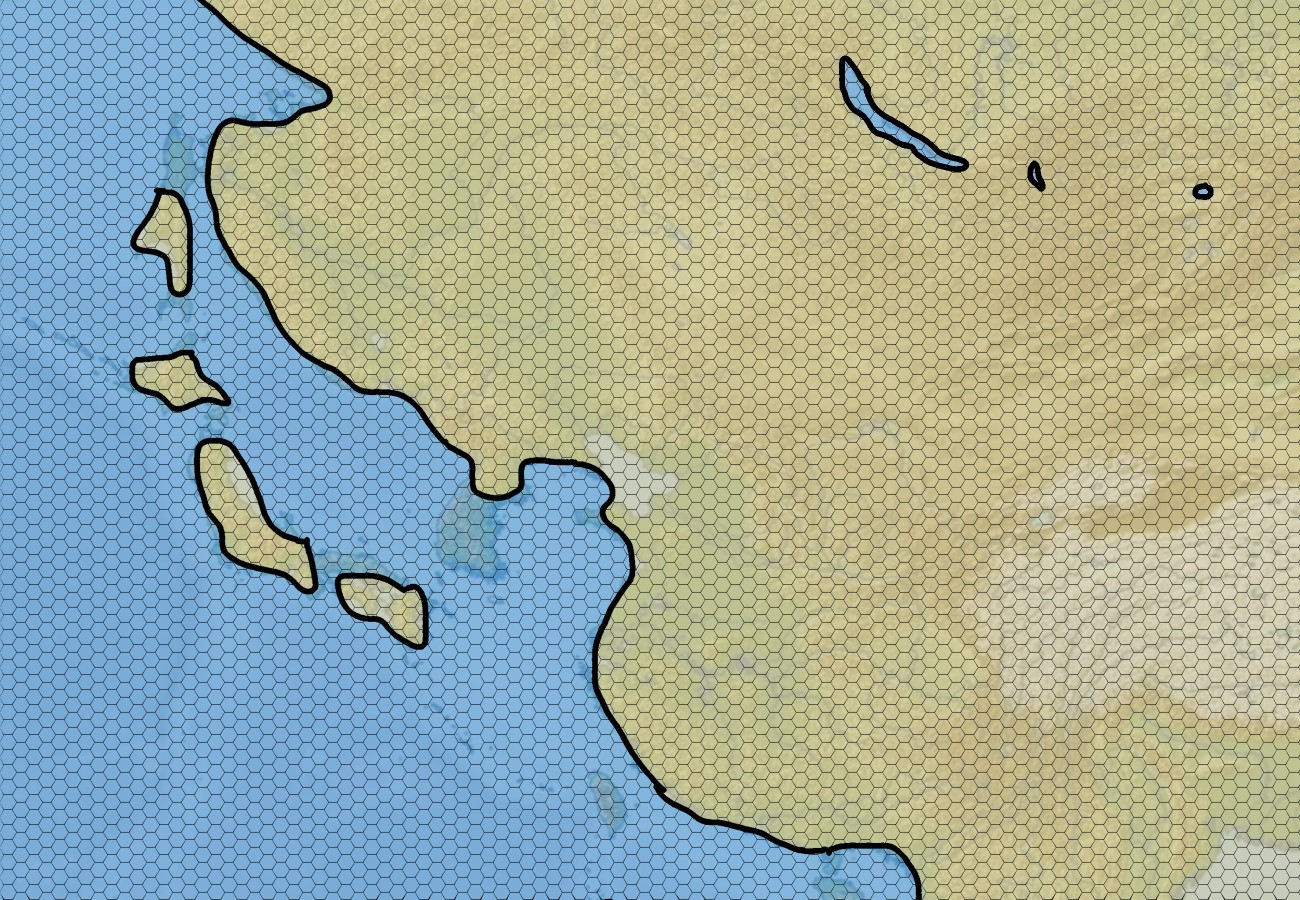

The core sensibility that is underlying the entire worldbuilding for Kaendor is the idea of being in this vast world of barely explored and largely uninhabited wilderness, which is full of amazing and alien creatures that are different from the generic European and North American wildlife of typical fantasy worlds. The forests and mountains are covered in grand ancient ruins that hold great magical wonders and mysteries. The world is wild and rugged and dominated by powerful natural forces, but also quiet, timeless, and pleasant. I guess you could say, romantic. A fantasy of a world that is simultaneously exciting and peaceful.

This is not an aesthetic that lends itself to complex intrigues or sprawling conflicts that cover the world in war and threaten it with destruction. But that doesn’t mean we can’t be exploring treacherous ruins and battling with leathal monsters. Taking stupid risks to discover something magical, and to take on great tasks to establish a place of quiet comfort in the middle of a rugged wilderness are spot on for the core ideals of Romanticism.

And I have in fact come across at least two cases where people have managed successfully to create engaging games that are catering to these very sentiments. The survival sandbox videogames Conan Exiles and Kenshi. Yes, the world of Conan is hyper violent and filled with manly men doing manly things. And manly women doing manly things. And the planet Kenshi is violent post-apocalyptic wasteland. But even with all the blood and grime, Sword & Sorcery and Wasteland Fiction are still fundamentally expressions of Romanticism.

Now both of these games gain a lot of their aesthetic payout from their visual presentation. Even though their graphics aren’t anything special, their visual design can often be gorgeous. This is something that obviously doesn’t translate to the medium of roleplaying games. No matter how much GMs might want to indulge in flowery environmental descriptions. But I think one of the key gameplay elements of both Conan Exiles and Kenshi that appeals to the romantic ideal is the construction of completely custom build home bases in nearly any spot you might want to pick. It’s the fantasy of carving out your own little corner of the world where you can shape everything exactly to your personal ideal. But for that you first have to acquire the resources that are needed to construct those buildings, and to neutralize the threat of dangerous creatures and hostile neighbors that also roam the area. And it’s in these encounters with the other actors that stand in your way of having the house of your dreams and enjoying it in peace that you can have the most amazing adventures. Adventures that are not scripted stories about uncovering the cool things some of the GM’s NPCs have already done, but instead constantly evolving sequences of making choices and dealing with the consequences of those choices. The kind of emerging stories that RPGs are uniquely capable of telling. The kind of adventures where RPGs as a medium can really shine.

I could talk for hours about my earliest adventures in Kenshi, which are some of the greatest experiences I ever had in any kinds of games. How two of my guys got separated from the rest in a bandit ambush and were spending the entire night hiding in a ditch with broken legs, only meters away from where the bandits had set up their campfires, blocking the narrow mountain pass to the stronghold where their friends had found safety. Or how the gang was desperately trying to finish the wall around their first compound before a group of approaching raiders reached them, only for the concrete mixer refusing to work because the previously constant winds had completely died down and the lone wind turbine refused to spin. Or how the compound later changed hands between my gang and bandits seven times, as each side was able to kick out the current occupants and chase them into the desert, but then was too beaten up to hold it when the next assault came.

And those are just the ones that happened from random encounters with the lowest level enemy type in the game, still within site of the starting town.

Dungeons & Dragons has toyed many times throughout its history with the idea of higher level PCs establishing their own stronghold in the wilderness. While a very cool sounding idea, from what I heard from people who played a lot when this mode of play was featured prominently in the rulebooks, this apprently saw only very little actual play. Many reasons have been hypothesized for this, but the most compelling sounding ones focus on the fact that the idea was to switch play from dungeon crawling to domain management, and that this was a switch that would be rather sudden, but also only very late in a campaign. And I think it wasn’t helped either by the rules for running a domain being a single player undertaking rather than a group activity as the dungeon crawling play.

A Campaign Structure

A good home base system should become part of the gameplay fairly early on in the campaign. It should supplement rather than replace the expeditions into the strange and dangerous wilderness, and it shouldn’t mean the end of the players playing together as a party. But I also think that the idea of becoming a ruler and dealing with government work and managing taxes doesn’t really appeal to the romantic fantasy of establishing your personal dream house overlooking the landscape.

So I am proposing a different kind of campaign structure that might work better to accomodate and evoke the themes I outlined above:

The PCs are individuals who for one reason or another chose to leave behind their old homes to seek their fortune in the borderlands, on the very edges of the lands that are explored and settled. These borderlands are a fairly conventional sandbox with a lot of old ruins and monster lairs scattered around. Theres both gold and silver to be found and ancient magic items and forgotten spells. New magic items can be made, but the process is complicated, slow, and expensive, which makes the dangerous activity of recovering lost items a worthwhile undertaking. Searching for magic items should be the main premise of the campaign, and the default activity for players to engage in if they don’t have anything else that is demanding their attention right now.

So far, so ordinary. But what I am thinking is to set things up in a way that establishing a permanent home base, and perhaps aditional base camps, somewhere in the sandbox would make the searches much more efficient. Places to store supplies. To safely lock away your money. Where you can produce the tools and other equipment that you’ll be using on your expedition. Where you can stable your pack animals and house your hirelings.

Exploring ruins in the wilderness is the main hook. But establishing a base should become a highly attractive measure to pursue that primary goal. Typically, that base is assumed to be a small castle staffed by the PCs’ hirelings. With settlers being recruited to set up farms nearby, whose tax payments will support the castle’s expenses. But you can really only have one lord who rules the domain, and theb you’re also required to deal with administration.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Instead, the home base could also be a village. Potentially a quite dispersed one. Simply by making the surrounding area more secure, the players could make the village more attractive to new settlers. And as the settlement grows in size, new services become available that the players can use. Animal breeders to increase the amount of pack animals that can be bought in any given time period. Potion makers who sell potions. Sages who can help deciphering clues about undiscovered treasure hoards. And of course an increasing stream of hirelings that can be recruited. Players can then each pick individually if they want their PCs to build some grand villa, or instead live in a shack half an hour away from the village square.

And that’s about all that I got so far. Not terribly much yet, but I think it’s a direction that might be interesting to explore.