I got big plans for another Kaendor campaign next year. I’ve been sharing bits and pieces on Mastodon, but now I want to put it all together in one place as an overview of what I’m working on.

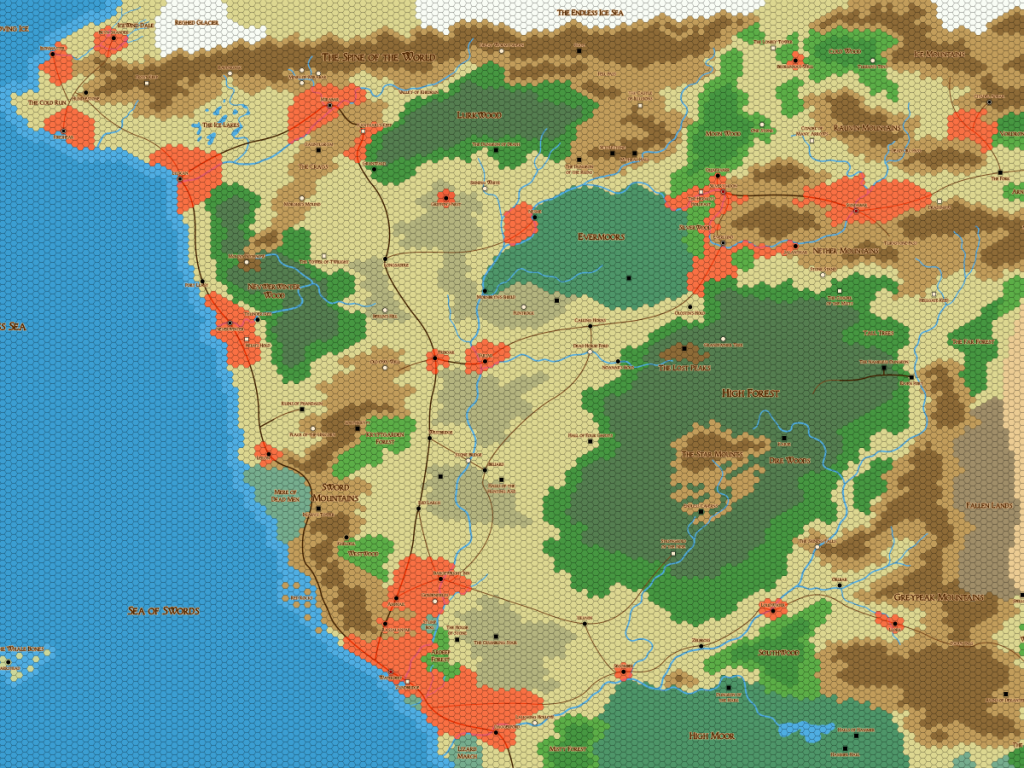

As far as I’ve been able to trace back, I started developing my own fantasy setting style all the way back in 2009. I’ve been reworking and revising it many times for several different campaigns and planned campaigns, but like Demon’s Souls, Dark Souls, and Elden Ring, I’ve been reusing places, monsters, gods, and names, and the overall cultural and supernatural structure for the world. Originally, everything started with the observation that the ancient history backstory for the northern Sword Coast of the Forgotten Realms setting sounds like a much more exciting place to play in than the world that is actually being described in its current state. This gave me the idea to use what information was available to “recreate” the High Forest from 4,000 years ago as a stand alone setting for my own campaign. This very quickly led to the realization that it would all just be a lot easier to drop the explicit references to the Forgotten Realms and create a new setting from scratch with the same ideas: A northern European environment that is home to great kingdoms of elves and dwarves, where dragons and giants still exist in large numbers and have an active presence in the world, where humans are a minor people of barbarians, and the ancient primeval forest still cover nearly all land between the seas and mountains. At the same time, I had also deeply fallen in love with Morrowind, and how it presents a fantasy world that doesn’t feel at all like medieval Europe, and not even any place on Earth. While most of the Elder Scrolls setting is much more conventional, Morrowind feels like it’s a medieval society that evolved independently on an alien planet. Having a world with giant reptiles and insects, and without horses, dogs, cows, and bears is an idea I find hugely fascinating and compelling.

After several iteration I eventually settled on the name Kaendor, and used that world in a campaign in 2020, which without doubt was the best campaign I ever ran, and one of the longest. But I had been unhappy with the D&D 5th edition rules we’ve been playing, and since that campaign ended three years ago, I’ve been exploring and experimenting with various new ideas to rebuild the world for the next campaign. Various ADHD related factors led to that next campaign being delayed much longer than I had ever expected, but things have finally settled in place enough so that I can commit to plans more than two or three months into the future. And I think spring 2024 is finally going to be the time where I’ll return to that world. Which will hopefully turn out even better than the last time.

After several iteration I eventually settled on the name Kaendor, and used that world in a campaign in 2020, which without doubt was the best campaign I ever ran, and one of the longest. But I had been unhappy with the D&D 5th edition rules we’ve been playing, and since that campaign ended three years ago, I’ve been exploring and experimenting with various new ideas to rebuild the world for the next campaign. Various ADHD related factors led to that next campaign being delayed much longer than I had ever expected, but things have finally settled in place enough so that I can commit to plans more than two or three months into the future. And I think spring 2024 is finally going to be the time where I’ll return to that world. Which will hopefully turn out even better than the last time.

The Kaendor 24 campaign will almost certainly be my first run with the new Dragonbane system that came out earlier this year. I’ve been going through plenty of systems in the last 10 years that each have their strengths and shortcoming regarding what I want them to do for my campaigns, but Dragonbane very much seems like the game I wanted to have from the beginning. The idea is to combine this system of character and combat rules with the travel, exploration, and domain rules from the D&D BECMI Expert and Companion sets. I want it to be a West Marches style sandbox game in which the players have a rough map of a region that is filled with ancient ruins, the strongholds of many minor lords, and several factions with hidden plans that they are working on. It is up to the players which of these elements they want to focus on and pursue, and the story of the campaign will consist of whatever consequences that will come from the players’ actions. There will be no script. Only faction leaders with their clearly specified goals, strongholds, and minions at their disposal. To that end, I believe the random tables to generate Court Sites and small ruins and dungeons fom Red Tide will be a fantastic resource.

After a many year infatuation with Frank Frazetta style barbarians and dinosaurs, I am planning a return to that very original idea of imagining a world in the style of 2nd edition Forgotten Realms but at a much earlier points in history. This means a world more in the style of Lerry Elmore and Tim Hildebrandt, full of rich green primeval forests and golden sunlight. But below (and beyond) that vibrant natural world lie the lands and places that predate the light of the sun and stars. These realms of the primordials are much more inspired by the dark blue of Bloodborne, Darkest Dungeon, Hollow Knight, and Thief, and their take on supernatural forces and beings. Which is a pretty strong contrast, but the more I’ve been playing with those ideas the more I think they actually make a very evocative combination. This incarnation of Kaendor has no demons, divine servants, or hells or godly realms. The supernatural world consists of just the primordials that predate the natural environment and the spirits that are part of it. These spirit can be quite demonic in their apearance and often weild powers over fire, but they are still very much beings of the forests and mountains that are their homes.

For a long time I really wanted to run campaigns in a Bronze Age setting, but I feel that concept never actually came across in the campaigns that I have run. With the earlier versions of the Forgotten Realms now being a stronger inspiration again, I am returning to a more medieval style again. But since I played a lot of Age of Empires II last winter, I’ve developed a new obsessive fascination with the 5th century era of Europe, where the last years of Antiquity transition into the start of the early Middle Ages. It’s the time of the Lombards, Goths, and Huns, who are basically Iron Age barbarian peoples who take over control of much of the failing Roman Empire, and create the first medieval societies in the process. It’s not classically ancient and not classically medieval. A bit of both, but also a bit something completely different from either. Which I think makes it a great reference pool for a setting that should feel like a completely separate world instead of generic medieval Europe with magic.

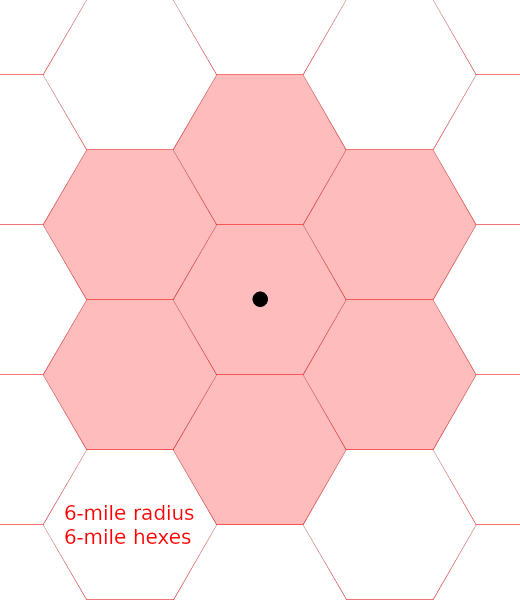

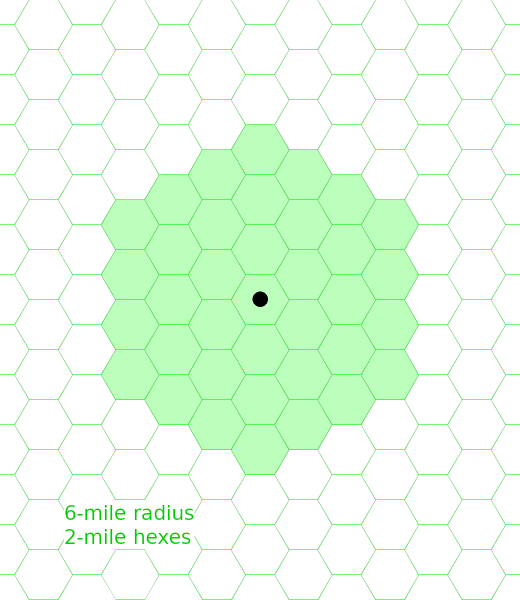

One thing that always strongly evoked the sense of a world being very far back in ancient times is to not have much in the way of classic kingdoms or empires. Instead, the main centers of civilization are a small number of city states whose direct area of control reaches only two or three days’ travel beyond their city walls at the most. Beyond that lies a vast, sparsely settled expanse in which small farming villages cluster around a hill fort town or the stronghold of a local warlord whose men can protect their turf from raids by neighboring domains or brigands. This is very much in the spirit of BECMI and the early Forgotten Realms, but I think that D&D had largely forgotten about that aspect as the fashion of RPGs changed throughout the 90s.

In a world with very few actual armies and fighting mostly taking place between minor lords or chiefs gathering a few dozen of their retainers with their men at arms (who are primarily wealthy farmers for most of the year), mercenaries have a lot of opportunities to make a living. And player characters are very much intended to be actual mercenary bands rather than adventuring parties. Traveling long distances through the wilderness while carrying both all their heavy gear needed to do their jobs and all the supplies for the journey means that it really isn’t an option to travel without several pack animals and camp followers that will wait in the relative safety outside while the PCs descend into dangerous ancient ruins. This is a play format that also works very well with having larger numbers of players who won’t be present to play in every game that is being run. PCs of absent players can always be assumed to be guarding the camp or the group’s temporary base or permanent stronghold, and are ready to drop back into the action at any moment.

One thing that has always been very central to my campaigns is that the world is dominated by wilderness that is not only vast, but also full of ancient ruined towers and strongholds. Since civilization is always very small and the influence of the spirits and the elements is always present and often chaotic, settlements and areas of habitation keep moving around a lot, and have always been. Few settlements are more than a few centuries old, and traces of much older settlements abandoned long ago can be found anywhere. Most towns are build in places that had once been home to a different people that left the area long ago for one reason and another. And sometimes these old remnants are much more ancient than any people alive could even imagine. There are several main layers of habitation that cover the wilderness of Kaendor whose creators are now largely unknown. But the further down one digs, the more inhuman their builders appear to get. Noticing the differences between ruins, and different depths of the same ruins, is something that I want to make a prominent feature in the exploration of ancient places that helps piecing together the places’ histories and getting hints of what strange powers might still be lingering in them.

It’s all a concept I am super excited about and I can’t wait to see this world getting back into action again.