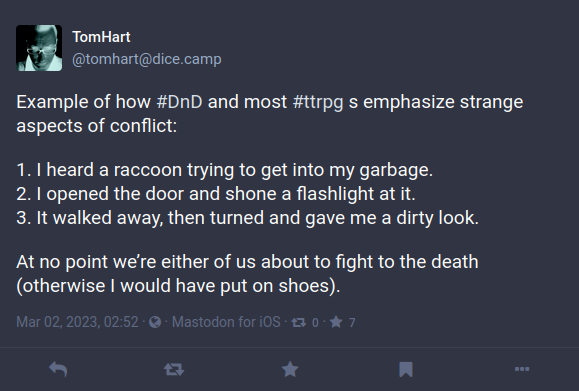

In just the last week, I had three encounters with people voicing their unhappiness with essentially the same issue they see with “D&D”. (By which I assume they mean 5th edition in particular.) I only now got around to watching Matt Colville’s video Why Are We Fighting? last weekend, but I think his previous video What Are Dungeons For? also talks about the same fundamental issue. Then there was the thread Structural Flaw of the D&D Combat System on Enworld on Monday, and then this morning I saw this post on Mastodon.

And every time I was thinking “This issue had been figured out 40 years ago. This is a solved problem!”

And every time I was thinking “This issue had been figured out 40 years ago. This is a solved problem!”

I wanted to write an article about why people should consider Old-School Essentials as a system for roleplaying campaigns about wilderness exploration a few weeks back, but gave up when I couldn’t get even just the introduction down to under 2,000 words after several attempts. But now seeing several people independently voicing frustration with what I see the same fundamental issue with “modern D&D”, I really want to tell more people about a possible great match for their needs that has been hiding right under their noses by preconceptions about “old D&D” and “dungeon crawling”. Yes, OSE is both that, but in my opinion the rules are also a fantastic system for combat light, high tension, interaction heavy, semi-freeform adventures about exploring strange and magical underground environments and journeys through fantastical wildernesses.

Background and Origin of the Rules

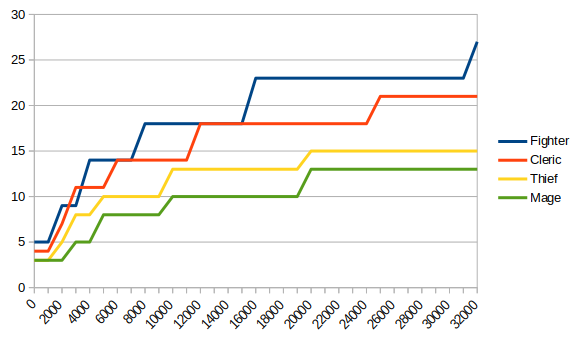

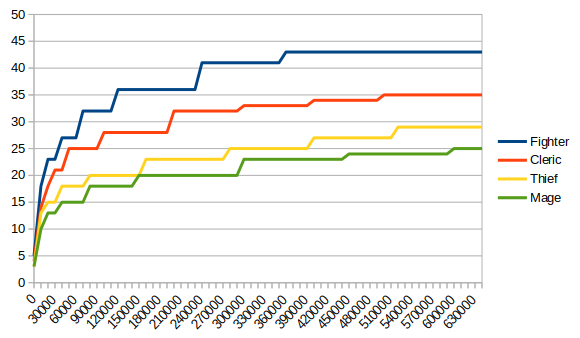

When Dungeons & Dragons came out in the 70s, it was considered a huge success within the sphere of an established wargaming hobby. But whatever qualities Gygax may have had as a game designer, he really did very poorly as a technical writer and editor. Both the original D&D game that was more a collection of reference tables for people who had been taught the game in person, and the greatly expanded AD&D game a few years later are among the most difficult games to get into just because of the big hurdle of simply deciphering what the explanations are trying to say. To make D&D more accessible to a wider audience, Tom Moldvay created the Basic Rules that were a drastically cut down version of AD&D with only four human classes, a single class for dwarves, elves, and halflings each, and only covered the first three experience levels. At the same time, David Cook put together the Expert rules that had the expanded class tables up to 14th level, more spells for higher levels, more monsters and magic items, and also the rules for outdoor scenarios. They both did a great job in creating a much more compact version of AD&D and making it vastly more accessible, and the Basic and Expert rules became a massive commercial success, now usually simply known as B/X. Two years later, the B/X rules got a new edition that was still mostly the same game, but also got the Companion expansion and later the Master and Immortal rules, which led to it being known as BECMI.

When WotC created 3rd edition and released it in 2000, the new game was very much an evolution of AD&D 2nd edition with the alternative BECMI system being largely forgotten and unknown to people like me who only got into D&D at that time. But the compact and lightweight nature of the original 1981 B/X rules made it particularly well suited to using it as the starting framework for heavy modifications and it became the default standard for OSR creators trying out more experimental things that drifted increasingly further away from the conventions of D&D during the early 2010. While the original Basic and Expert rules are still available as pdfs, getting print versions in good conditions after 40 years is of course getting only more difficult, and while having the Expert rules separate from the Basic rules is really quite useful when learning the game, it’s a bit inconvenient to have spells, magic items, and monsters in two different books.

Old-School Essentials was created to address both these issues by combining the material from both books into a single text and putting it back into print. But in regards to the content of the rules, OSE and B/X are identical, with the one exception that the books have the attack bonuses and AC values for using the modern attack roll system of “d20 + bonuses vs AC” listed in all tables and description, alongside the original TSR system of attack tables. So if you want to use the modern (superior!) system, you don’t have to make the conversion yourself as with other retroclones and have the numbers you need right in the book.

Roleplaying Dungeon Crawling

Now, finally (after 800 words) to the main subject of this article. What makes OSE an interesting alternative to modern D&D for people who have gotten bored and frustrated with the slog of endless and mindless combat and are looking for something that makes exploration fun and exciting and has a stronger focus on interacting with the environment and the people and creatures that inhabit it?

On a first look at the rules (it’s all available online as an SRD), OSE seems a really strange choice for that purpose. It’s all about dungeon crawling and the rules for PC actions mostly just cover combat and spells and almost nothing else. There are no skills and no rules for social interactions. And the XP system is all about collecting as much gold coins and possible. That sound more like a hack and slash dungeon crawler than a roleplayin game. This seems worse than 5th and 3rd edition in those regards, not better.

One of the issues raised in one of the two videos I linked to above talks about how WotC was very successful in getting D&D established as the game that can be everything to all people. And in the process, their editions turned into a game that isn’t actually about anything specific. What is D&D about? What is the goal? How are individual mechanics set up to further that goal? These games provide mechanics to do a lot of things, but they don’t have a structure. Borrowing a term from videogame design, they have no gameplay loops. That makes the rules flexible and easy to adapt to many different kinds of campaign. But in turn they lack mechanics that specifically support the kind of adventures you have picked from your campaign by providing structures that take work of the GM’s shoulders and help players to be more proactive. I believe that much of the burden on the GM when it comes to preparing adventures and moving things along, and what can make playing D&D feel like a slog that drags on to players, comes from this lack of mechanical support for specific adventure styles.

The rules of Old-School Essentials all come together as a game that is designed with a very clear focus: It’s a game in which the PCs go into old ruins in the wilderness and face their many dangers to return with hauls of gold and other riches.

This does of course greatly reduce the possibilities of what kinds of adventures you can run with OSE. If you want to run a game in which dungeons do not take a central role and you are not interested in playing characters who are searching for riches in the face of great danger, then OSE does not have much to offer to you. But what the system of interdependent mechanics and procedures does provide is very strong support to make such explorations of strange undergrounds in mysterious wildernesses a game of great adventure in which the players are in charge of their fates and their choices determine what paths their stories will take. In many ways, I would even argue that OSE is a game for campaigns that are more similar to Apocalypse World or Blades in the Dark than to the adventures and campaigns published for modern D&D.

Most of the quirks of early D&D need to be looked at in the context of adventures the game wants to produce and how this mechanic interacts with the other rules that make up the whole system. In most RPGs I’ve read over the years now, mechanic seem to be created to figure out what die to roll when a player wants to do a specific action. But the old B/X rules used by OSE are much more clever than that. You don’t just have mechanics to make dice roles for actions, you also have procedures that create situations and structure that give players the means to chart their own course instead of having to pick between two choices that the GM offers to them. All of these elements create a unified system in the strictest sense of the word, where every mechanic influences several others, and together they create results that you wouldn’t immediately expect if you just look at individual mechanics in isolation from the others. How this works is what I’ll be trying to explain in the rest of this article.

Credit goes mostly to Gus L’s Classic Dungeon Crawl series and Joseph Manola’s General Purpose posts. Everything about all of this I only know because they explained it.

XP for Gold is actually briliant

When I first heard that in older editions of D&D characters gained experience and advanced in levels based on the amount of treasure they collect around 2004, I thought that this was the dumbest rule that I had ever heard of. How is the amount of gold in your purse connected to getting better at swordfighting or learning more powerful spells? Getting better at playing lute from fighting monsters also doesn’t make much sense, but XP for gold seemed like a much more terrible mechanic.

What really is the purpose of XP? The reason why we want to reward certain actions and behaviors with XP but don’t give XP for others is to nudge the players to seek out opportunities to engage in those actions. When we are playing a campaign based on a premise that the PCs will have adventures similar to a certain type of fiction, then we want to create a lot of situations in the campaign that match that premise. OSE is a game about characters going into old ruins in the wilderness to search for treasure. By giving the players XP reward for collecting treasures and putting those treasures into old ruins, the players will automatically end up going to lots of dungeons and exploring them from top to bottom. And at no point do you have to make the decision as the GM what you want the players to do next. All you have to do is to make sure that there are several dungeons (could just be three) that have more than one path to explore them. The players are allowed to do anything they want and can think of, but by letting them know that they will be rewarded if they can bring treasure out of a dungeon, they always know something that they can do next if there is currently nothing else pressing to them.

Another great thing about giving most XP for treasure but only little XP for defeating enemies (Moldvay recommends to aim for 3/4 XP from treasure and 1/4 XP from creatures when filling dungeons with content) is that it separates the questions of whether it is worth it to risk a deadly fight and whether they want to try getting a treasure they can see ahead. As Obi-Wan Kenobi once said “There are alternatives to fighting”. This is super important. By playing the emphasis on returning with treasure over defeating enemies in battle, you introduce the whole concept of stealing treasures through trickery rather than killing their guardians. This is something that gets completely lost in games where XP for defeating enemies is the default way to advance characters. As players, we always want XP. And if we only get XP by fighting monsters, we seek out fights with monsters. As many fights as possible. If a monster seems to strong to defeat it, then we probably plan to come back later when we’re stronger and get the XP then. Monsters not fought are XPs left unclaimed! And that is where the Murderhobo spawns as the only logical consequence.

In the OSE rules, it is assumed that monsters have their treasures stashed away in their lairs and don’t carry them on their bodies. You can sneak past the monster, lure it away, or distract it otherwise to get at its treasure without having to fight it at all. And perhaps even more importantly, wandering monsters that players run into in random encounters don’t have a treasure stash at all. This makes random encounters something you want to avoid. Random encounters have all the risk of losing health and spells and perhaps even characters getting killed, but don’t provide any meaningful rewards in the form of XP. In contrast, when combat is the primary source of XP, then random encounters are extra XP that come to you.

XP for treasure creates a kind of fiction in the game that is very different from post-Dragonlance D&D. In this game the PCs are treasure hunters, not monster slayers. And this allows you to present them with enemies that are actually scary instead of having to limit the dungeon to only monsters that do not pose a real threat. It’s now a survival game in which it makes sense to sneak past enemies and run away from them, and doing so can actually be an efficient way to gain XP faster than a form of failure and giving up.

Encumbrance is important

Encumbrance is one of the most hated mechanics in RPG. And for good reasons. Having to add the weight of each item you pick up to your total and subtracting the weight of every item you use up or throw away is a lot of bookkeeping. And inevitably there will be mistaken and then you have to do a full weight count of every item on your character sheet all over again. This sucks, this is terrible. And people are completely justified to not want to deal with it. Thankfully, there are much better ways to track how much stuff characters are carrying and how much it slows them down by making weights a little bit more abstract. Because having travel speed affected by how much gear the characters carry is serving an extremely important function in the greater exploration system. I believe people not bothering with calculating encumbrance because the rules in the books are too annoying was the first loose stone that made the entire complex exploration system of D&D collapse and disappear in later editions.

In the dungeon exploration and wilderness travel rules of OSE, random encounters are checked at specific intervals of time. The amount of random encounters a party will have depends on how much time they spend in a dungeon or how long it takes to reach the destination of a journey. And this depends entirely on how fast the party can travel. Ideally, you always want to travel as fast as possible to minimize the amount of random encounters. But a light load with no speed penalty really doesn’t let you carry a lot of things. You need your weapons and your armor. You also need food and water. You will need torches, lamp oil and arrows. You probably also want to have someone in the party having a rope or two, and crowbars, sledgehammers, shovels, and so on. Also sleeping bags and tents. And on top of all of that, while you are exploring the dungeon and make the journey back to the surface and then home, you’ll be increasingly loaded down by all the heavy treasures you collected.

If you bring too much, you get too much slowed down, have lots of random encounters, and might die. If you bring too little and things don’t work out just as planned, you might run out of supplies necessary to survive and will have to make detours or take greater risks. Perhaps you could leave things you no longer need in the dungeon behind to make more room for treasure you want to carry home. But then, who knows if you’re really not going to need them during the return journey?

There are no correct answers to these questions, and that’s what makes encumbrance such a brilliant mechanic in the exploration system. It creates constant tension and permanent doubt, and there are infinite possible combination for your characters loadout. It is also what will create situations in which the characters are dangerously low on certain supplies and force the players to go on unplanned side adventures to get water or stumble around blindly in the dark. Or at least have the party race through the tunnels in panic as their last remaining torch keeps getting dangerously low. Exploration as an adventure does not work without encumbrance.

Also, the amount of gold character need to gain new levels at the higher levels increase exponentially and pretty soon reach ridiculous levels. Even if the party has a bag of holding or two, the hauls at higher level get so big that it can take dozens of mules to carry all the stuff in one go. And the mules can also help a lot with carrying all the supplies that players might want to bring on a longer journey. Of course, you can’t take all these mules inside of dungeons and when left alone any bandit or griffon passing by can just snatch them up and be on their way. So the players probably will have to hire mercenaries to guard the supply train. And maybe get some retainers to look over the mercenaries while their PCs are gone inside the dungeon for hours on end.

Reaction Rolls and Morale Checks

The reaction roll is something that has disappeared from D&D long ago and I absolutely have no idea why. I assume its part of the fallout of the Dragonlance transformation that turned RPGs from players developing campaigns through their actions and choices as they went into a medium of adventure writers and GMs narrating a written out stories to the players. But together with dropping XP for treasure but keeping XP for defeating enemies, dropping the reaction roll is one of the main things that creates the murderhobo phenomenon and makes it pretty much inevitable.

In the OSE rules, monsters and NPCs encountered in a room or as wandering encounters have no default disposition towards the PCs. When the type of the creature or its placement really only allows for one plausible reaction of the monsters, then that’s what happens. For example an ancient crypt in which the dead bodies have risen as zombies. What else could they do but attack the living and try eating their brains? Or randomly encountering a group of guard looking for intruders into the castle? Of course they will tell the PCs to drop their weapons and get arrested. But those situation are generally rare and meant to be the exception. Normally, when creatures are encountered in rooms or wandering, a reaction roll is made.

Now as much as I praised Moldvay and Cook for making the D&D rules more accessible and easy to comprehend, the explanation of the different results for a reaction roll are super vague. There’s really only one or two words for each number with no elaboration on how that might look in practice. It’s also not quite clear how a character’s Charisma modifier to reaction rolls is supposed to be applied. (But I do have an idea how you can do it.) But having spend some time with that section of the rules, I think the following is really just the only thing that makes sense for what was originally intended.

- There is a 3% chance that the creatures see the party and immediately charges at them and try to kill them.

- There is a 25% chance that the creatures have a problem with the PCs being there and will threaten them to leave the area, try to rob them, or otherwise make demands on what the players will have to do to not have it devolve into a fight.

- There is a 44% chance that the creatures are undecided on what to do and wait to see what the PCs are doing next, perhaps followed by another roll with a modifier based on the PCs behavior.

- There is a 25% chance that the creatures want to avoid a fight and will try to negotiate with the PCs or retreat from the area to avoid violence.

- And finally there is a 3% chance that the creatures see the PCs as welcomed guest and offer to provide information and assistance as it is within their means.

Say the PCs run into a group of bandits and the reaction roll makes them friendly. The bandits could mistake the PCs as new member of their gang or visitors they were expecting. Or they could assume the PCs have come to see their leader and join them. Or they are having a problem and think the PCs are another group of bandits and they could join forces to deal with the threat and split the spoils. Imagine the players encounter an ogre in his cave and he offers them pieces of his roasted halfling over the fire? That would be a very interesting situation for players to respond to.

Morale checks have lingered around much longer, but I’ve never really seen them given any real attention. Even back in B/X they were listed as optional, but they really serve a very important function. The idea is that under certain conditions, there is a chance that a group of enemies will panic and flee from a fight. The first morale check is made when the first member of a group goes down, killed or otherwise incapacitated. That’s when things suddenly become very real for everyone involved. Another check is made when a group has lost half its members. At that point, it’s generally becoming clear that the remaining ones probably won’t be surviving either. I personally also like to make morale checks when the leader or a particularly big and impressive ally of the group is killed. When a group of 12 goblins and an oger is two goblins down and the oger falls, that’s a very good reason for the goblins to reconsider their chances, even if their group is only one quarter of their fighters down. Successful morale checks of course don’t preclude the fighters to to make an informed rational decision that the fight is not worth to continue and order an organized retreat, or to offer their surrender. It just means that they don’t start blindly running away in terror.

What these two mechanics bring to the table should be very obvious. Not only is it not desirable for players to fight everything in the dungeon and the wilderness, most of the time they might not even have to and still can continue on their path without having to retreat back. It also provides many great opportunities to have interesting unplanned interactions with NPCs during explorations.

As GM, you could of course always decide what reaction towards the PCs randomly encountered creatures will have. But in my experience, in the heat of the action when all the players are looking at you eager to hear what happens with the things they just encountered, it’s just overwhelming tempting to always go with the default option that takes the least effort and can sprung into action immediately. “They attack.” By having the reaction roll as part of an established procedure for every encounter, you have a tool that always makes you at least take a moment to consider your options before settling on the easiest one. If the roll gives you a reaction and you have no clue how that could possibly work with that creature in that situation, you still always have the option to pick yourself how it should logically react. But having a dice roll always make a suggested outcome first is a very useful tool to have.

OSE might be worth a look

At 4,000 words, this is still only a look at the surface of what makes these 42 year old rules an interesting option for GMs and groups that think generic modern D&D can be a slog with too much mindless combat that takes way too much work and time to prepare for. I’m still not really happy with how this has come out and I am sure there are many more intricacies that would be worth mentioning, but I don’t think I’m going to get it much better than this in any reasonable time frame. If any of this sounds interesting and you want to know more in a lot more detail, I recommend again the Classic Dungeon Crawl series by Gus L I linked to above. He does a much better job at it, but also takes considerably more than 4,000 words.