A Gator Man is basically just a beefed up lizard man with the head of an aligator instead of a lzard. In actual combat, they are a lot meaner, though. Gator men stand well over 2 meters tall and at 7 Hit Dice really have a lot of hit points and good chances to hit which are well beyond what you usually get from humanoid monsters. They also swim 50% faster than human characters run, which can make them very mean ambushers. They attack with normal weapons, but these completely pale compared to their bite, which deals a massive 3d6 damage. Groups of them are usually lead by a chief, who is even bigger and meaner and has a bite that deals 4d6 damage. When encountered by low level characters, they probably simply bite their head off!

A Hephaeston is a giant for high level adventures. It’s 8 meters tall and has intimidating 25 Hit Dice, which should be well over 100 hit points. The skin of a hephaeston is like iron and gives him a very high armor class and can only be injured by magical weapons. It is completely immune to mind affecting magic, all spells of 1st and 2nd level, and fire. Though I think by the time a group of player characters has any chance to fight this guy, they probably wouldn’t attempt to hurt him with nonmagical weapons and low-level spells anyway. The amount of damage it can dish out is staggering. When attacking with a weapon, it deals 4d10 points of damage and it also has the option to attack with a free hand as well, which also deals impressive 3d10 points of damage. If that bitch slap from hell hits with an 18 or higher, the hephaeston grabs the character and smashes him into the ground for another 5d6 damage. This is so funny I wonder if anyone would ever make make a hephaeston fight with a shield. In addition, it also has the ability to levitate iron objects (to throw on people, I assume), make an iron object get red hot, or magically create a wall of solid iron. Fighting one of these guys really doesn’t sound fun. Or very fun, depending on how you look at it. Fortunately, hephaestons live alone.

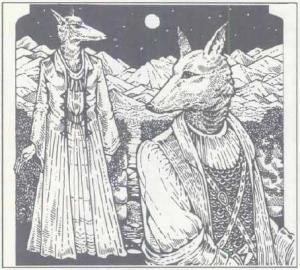

The Hutaakans are probably one of the most iconic creatures of the Known World. Which means that most of you have probably never heard of them. Hutaakans are humanoids with jackal-like heads but are otherwise very similar to humans or elves. In the ancient past, they ruled over a small empire but have almost disappeard by now, with only a few groups remaining in remote mountain cities. They are not particulary strong and have no real special abilities other than being able to see in the dark and being quite sneaky. They are highly civilized and ruled by a caste of priests. Overall, they are really very similar to stereotypical elves with dog heads and priests instead of wizards. It’s mostly their place in the Known World setting that makes them popular, but as generic monster for games in other worlds there really isn’t anything remarkable about them. Continue reading “Fantasy Safari: Creature Catalogue (BECMI), Part 2”