The Basic/Expert rules are the system that keeps on giving. At only 121 pages (of which 43 are monster and treasure descriptions), they would make a pretty thin rulebook and still I keep coming back to them to reread various sections over and over. I’ve seen people considering the ambiguities and unfinished nature of some rules to be a virtue many times, but I don’t consider it good design or even intentional. I’m quite certain that Moldvay and Cook mostly had specific rulings in mind but were not aware that they didn’t sufficiently communicate them in a clear way, and possibly in some cases simply copied things that Gygax had written before without really understanding how it’s supposed to work either. I’m usually not too hard on this, giving them some leeway considering that they had no real reference for what they were doing and making things up as they went. And with rules that into only 78 pages, filling in the gaps is not that much amount of work.

One section I was going over again recently are the mechanics for Reaction Rolls. The reaction roll is used to determine how randomly encountered creatures react to the party, if their behavior isn’t already obvious given their nature and circumstances of their encounter. Creatures like zombies always attack everything they encounter. Goblins always attack when they encounter dwarves. And if you have the party trying to sneak into a guarded enemy stronghold and they run into a guard patrol, the attitude of the guards is also obvious. The Reaction Roll is for situations in which the reaction of the creatures could be anything. But there’s still a lot of ambiguity left. What are you supposed to do with “Uncertain, monster confused”, which is the most likely of all reactions? How is it different from “No attack, monster leaves or considers offers”? The reaction roll is also modified by a character’s Charisma score. But whose charisma score? And if the Charisma score is 13 or higher, the result of “Immediate attack” is impossible to happen. So after pondering the issues over several days, I came up with the following procedure. I believe it mostly just fills in some blanks without really changing anything that is printed on the pages.

Beginning an Encounter

An encounter can start in two ways: The party enters an area in which monsters are already present, or the GM made a roll for Wandering Monsters for that turn. In the order of events for every turn (10 minutes of dungeon exploration) the first step is rolling for wandering monsters. The second step is “moving, entering rooms, listening at doors, and searching the environment”. Dealing with monsters comes as the third step. I think this order is significant because it can mean that wandering monsters can stumble into a room while the party is in the process of searching it. The random encounter is something that happens within the turn, not between turns.

Surprise

If the party and monsters encounter each other, the next steps are determining the distance at which they can become aware of each other, and rolling for surprise. These two steps happen basically at the same time and it doesn’t appear to matter which of the two rolls you make first. But I think it’s actually more convenient to roll surprise first and determine the distance after.

To roll for surprise, both the party and the monsters roll a d6. By default, a 1 or 2 means that they are surprised, while a 3 to 6 means that they are not. Two d6s allow for 36 possible results that cover four different outcomes.

| Odds |

Outcome |

| 4 in 36 |

Both sides are surprised. |

| 8 in 36 |

Party is surprised, monsters are not. |

| 8 in 36 |

Monsters are surprised, party is not. |

| 16 in 36 |

Neither side is surprised. |

Some monsters have a special ability that makes the party getting surprised by them on a roll of 1 to 3 or even 1 to 4, which significantly changes the odds to get the jump on the party in their favor. (A monster ability that modifies the party’s roll instead of their own roll isn’t very elegant, but it’s probably the least complicated way to get the desired result.)

The results of both sides being surprised and neither side being surprised are basically identical. However, I’ve seen a rule somewhere, and to my actual surprised it’s not in B/X, that in the case of both sides being surprised, the encounter distance should be half of what it would be in the other three outcomes. I really like it and so I’m mentioning it here anyway. This is also why I would make the roll for the encounter distance after the roll for surprise. Inside a dungeon, the distance is 2d6 x 10 feet, outdoors it’s 4d6 x 10 yards (or 4d6 x 30 feet, because we really don’t need two different units of measurement).

Something that surprised me coming from later editions is that the rules for surprise don’t really seem to take into account that one side or the other could by lying in ambush, or have time to quickly set one up. However, the Expert rules state that a group of three or more gains surprise outdoors they could be set up to have surrounded the other side. Maybe the idea is that even when you see a light at the next corner or hear footsteps approaching, there just isn’t enough time to set a proper ambush indoors. But I am a big fan of sneakiness myself, and I think it should absolutely be possible for players to avoid getting noticed by the wandering monsters, or quietly retreat from an area that has unaware monsters inside.

The rules as they are written only state that “those not surprised my move and attack the first round, and the surprised enemy may not”. I think the whole game becomes much more interesting if the side that has surprise can use its turn during that first round to back away without the surprised side becoming aware of them. Not only can it be a great opportunity for fun shenangians on the players’ side, it can also be interesting to have monsters stalking them in secret and wait for a good opportunity to strike.

Reaction

After surprise and distance have been determined, the sixth step is the Reaction Roll. As I mentioned earlier, the reaction roll is modified by Charisma. But whose Charisma actually? I long assumed that it would be the character who is walking at the head of the column or perhaps the party member with the highest Charisma, but that never really felt right since there is no indication either way.

The new idea I got recently, and which is the reason for this entire post, is that the reaction modifier for high or low Charisma only applies if a PC has the opportunity to talk to the monsters before a fight breaks out. If the monsters are surprised but the party is not, one of the PCs can hail the monsters and they make a reaction roll modified by the PC’s Charisma. If both or neither side are surprised and the party wins initiative for the first round of the encounter, the players also have an opportunity to hail the other group.

There is also the possibility that the monsters surprise the party or they win initiative, and their reaction is “Uncertain, monster confused”, which is the most likely result for an unmodified 2d6 roll. I’ve seen some retroclones rephrase this result as the monsters waiting to see what happens, which I think is a great interpretation. What you get is the monsters simply doing nothing for now. Then when it’s the party’s turn and the party is aware of the monsters, the players have another opportunity to hail them. At which point you could make a second reaction roll, but this time modified by the respective character’s Charisma.

And there’s actually something in the order of events for each exploration turn that supports that. Step six is making a reaction roll, but step seven, the resolution of the reaction, says “If both sides are willing to talk , the DM rolls for monster reactions and initiative, as necessary.” Making two reaction rolls is already written into the rules as they were printed. And I think it makes perfect sense to have a character’s Charisma modify a reaction roll only in those cases where that character is talking to the other groups. In situations where the monsters spot the party but the party is not aware of them, I think the reaction roll should be done without any modifiers at all. It’s of course also possible that the players might think of something so convincing that no reaction roll is necessary at all. If for example they encounter a group of guards and know the password to identify themselves as people who have permission to be in the place, then making a reaction roll can become moot. In the same way, if the party has surprised and decides to attack immediately and ask questions later, no reaction roll is necessary either. (Though a morale check might be.)

The Charisma Modifier Anomaly

Unlike in AD&D, the modifiers to various things based on the various ability scores are quite consistent in Basic. An 18 in Strength gives you a +3 bonus to melee attack rolls and melee damage, an 18 in Dexterity gives you a +3 bonus to ranged attack rolls and Armor Class, and an 18 in Constitution gives you a +3 bonus when rolling your hit points for each level. But Charisma stands out. An 18 in Charisma gives you only a +2 bonus to Reaction rolls instead of +3, and a 16 or 17 only a +1 bonus instead of +2. Some retroclones fix this by applying the same modifiers to all six ability scores, and I actually did this myself in the past. But I now think that this inconsistency is not an oversight but actually a deliberate choice.

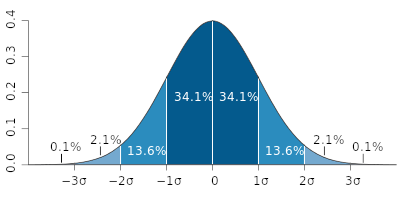

The modifier in question is not a generic modifier to Charisma rolls, but specifically an “Adjustment to Reactions”. Reaction rolls are its only intended application (though this includes retainer hiring reactions for which the following calculations apply equally). The Reaction roll is 2d6, and the Reaction table lists results from 2 to 12. The “Immediate attack” result can only happen on a 2 (or lower, one presumes), and the “Enthusiastic friendship” result happens on a 12 (or higher). If you get a +1 bonus to the roll, a result of 2 becomes already impossible. You can’t go lower than 3 and get “Hostile, possible attack”. Which is one more argument why some Reaction rolls should be done without applying Charisma modifiers. But not only that, the 2d6 also give us a bell curve and shifting a bell curve sideways results in often very significant changes in the odds for any given value. When you get a +3 bonus to the Reaction roll, even the hostile result only has a probability of 3%. Pretty much anything would be somewhat friendly if you’d happen to have someone with 18 Charisma doing the talking for the group.

But I think the +3 bonus from an 18 is not even the main reason for why the modifiers are different for Charisma. The chance for any given Character to get a randomly rolled 18 on 3d6 is under 0.5%. In a group of four characters, that’s still below a 2% chance for any of the characters to have an 18, and that player might not even want to do all the talking with everything they run into. It’s an unlikely scenario. But the chance for any character to randomly roll a Charisma score of 16, 17, or 18 is almost 5%, and getting someone in a party of four with a 16 or better is 17%. And a bonus of +2 to Reaction rolls is still really big. At +2, you have a 17% chance for a friendly reaction and only an 8% for a hostile one. With a 42% chance for monsters to negotiate. That frankly doesn’t sound particularly fun to me. Having the odds for this scenario being only 2% for any given party of four instead of 17% seems a very sensible change to me, even if it breaks the beautiful symmetry of ability score modifiers.

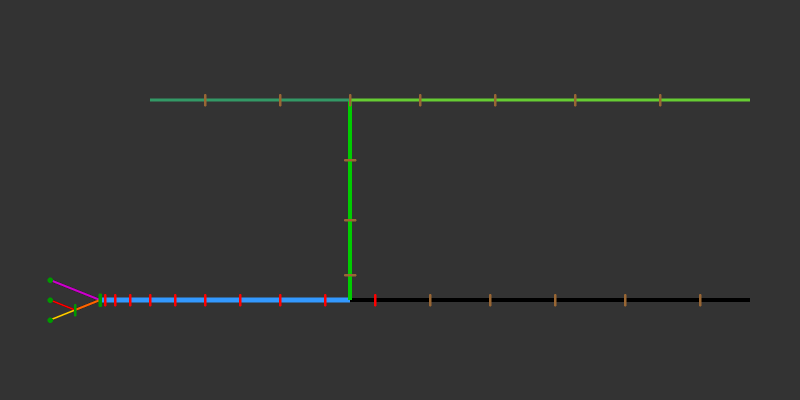

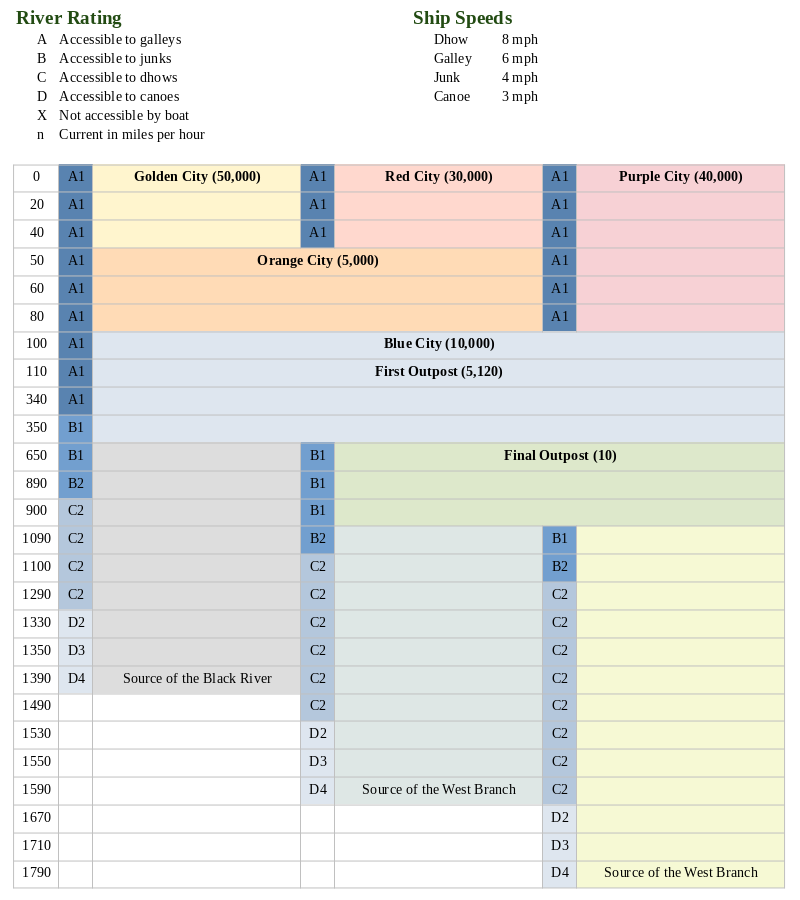

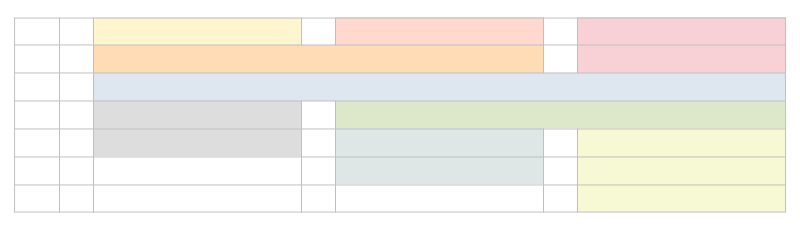

I then turned the same information into a big table. Below you have a heavily cropped down version to show the principle of how it works. The real thing I made actually has 180 rows over five pages, but most are still completely empty at this point. The principle is basically the same as in Ultraviolet Grasslands, but without the illustrations. I find this easier for river that curves and fans out, compared to the more or less straight trade routes in UVG, and it also allows to make more notes without making a huge unreadable mess. As a tool for GMs to use at the table, I think this plain look isn’t a bad thing.

I then turned the same information into a big table. Below you have a heavily cropped down version to show the principle of how it works. The real thing I made actually has 180 rows over five pages, but most are still completely empty at this point. The principle is basically the same as in Ultraviolet Grasslands, but without the illustrations. I find this easier for river that curves and fans out, compared to the more or less straight trade routes in UVG, and it also allows to make more notes without making a huge unreadable mess. As a tool for GMs to use at the table, I think this plain look isn’t a bad thing. Getting the whole thing set up was a bit tricky, so here’s how I did it: Since I have only three main branches at any given point of the river, I made a table with seven columns. I think you could also do it with four branches and fit nine columns on one page, but more than that probably makes the thing more a nuisance to read than a help. I found that my river has seven different combinations of parallel running branches, so I made the table with seven rows as well. At this point you first set the column widths that you want, because this will be a total bitch if you try adjusting those later. After that you merge cells together as the river branches fork and meet, which in my case looked like this.

Getting the whole thing set up was a bit tricky, so here’s how I did it: Since I have only three main branches at any given point of the river, I made a table with seven columns. I think you could also do it with four branches and fit nine columns on one page, but more than that probably makes the thing more a nuisance to read than a help. I found that my river has seven different combinations of parallel running branches, so I made the table with seven rows as well. At this point you first set the column widths that you want, because this will be a total bitch if you try adjusting those later. After that you merge cells together as the river branches fork and meet, which in my case looked like this. At this point, you can simple select and row and use “add rows below” or whatever your program calls it, and you should get an identical row to the one that you had selected. Then add mile markers to the leftmost row, and you’re done.

At this point, you can simple select and row and use “add rows below” or whatever your program calls it, and you should get an identical row to the one that you had selected. Then add mile markers to the leftmost row, and you’re done.