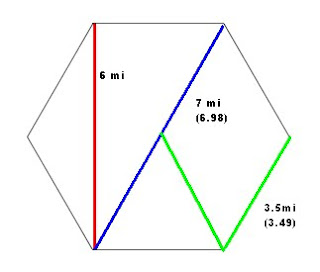

Expanding on my table for wilderness travel rates from a few days ago. For maximum efficiency, I am simply listing travel rates in 6-mile hexes. I think in the same way that a 10-minute Turn is not exactly 60 rounds or 600 seconds, we don’t need to treat a 6-mile hex as exactly ….31680 feet. (I had to look that up, and so would you. Those units are stupid!) In actual play, both duration and distance are abstract fiction that don’t relate to anything physical. And characters in the game world would not have actually have any means to measure either distance or time with any accuracy anyway. In a game, if players ask an NPC for a distance to a place or how long it would take to get there, that NPC would give them a rough guess like “some 10 miles” or “three days, if you keep a good pace”. That’s good enough on the players side. When I run wilderness adventures, I am fully in the camp of “the players never get to see any hex maps”. The hex map is a tool for the GM, just like random encounter tables. And for the purpose of telling the players when they arrive at a point, you really only need hexes. Miles are meaningless from a mechanical point. Or at least they are if you have a system for travel speeds in place that doesn’t have any granularity smaller than a hex. Which is what the following tables are all about.

Land Travel

| Encumbrance | Easy Terrain |

Difficult Terrain |

| Unencumbered | 6 hexes | 3 hexes |

| Encumbered | 4 hexes | 2 hexes |

| Heavily Encumbered | 2 hexes | 1 hex |

As I mentioned in my previous post, this is based on the assumption that a healthy adventurer with no significant load can cover 36 miles on a road or easy ground in a day. That would actually be quite impressive for a real human, but still plausible. However, in practice characters traveling through the wilderness to explore dangerous ruins and caves will be carrying quite a lot of stuff, and mostly deal with difficult terrain once they get off the roads, so that travel rate will rarely come up in actual play. So for the sake of easy use by the GM, I have no issue with that table maybe getting a bit high.

River Travel

| River Speed |

Upriver |

Downriver |

| Base Speed | 4 hexes | 4 hexes |

| Slow Flow | 3 hexes | 5 hexes |

| Fast Flow | 2 hexes | 6 hexes |

| Rapid Flow | 1 hex | 7 hexes |

From all I could find, going at 3 miles per hour ± the speed of the water is a pretty common speed when paddling on a river. Take that by 8 hours and you get 24 miles per day, or 4 hexes. If you go with the water flow, you’re going to get a bit more, if you’re going against it, you’ll get a bit less. If you wanted to, you could probably quite easily calculate what the flow speeds in the table above would be in miles per hour. But since player character’s won’t be measuring that during play, “slow”, “fast” an “rapid” are good enough for me.

Switching Pace

Something that I think would be neat to have is a system in which you can seamlessly have the party switch from one pace to another, like going a certain distance by boat, then continuing by foot on a road for a while, and covering the rest of the day’s travel on a mountain path. It could be done, but for that you really would need 1-mile hexes, and that’s just way too small for my own needs. At this point, I am diverting from my usual approach to get the mechanics all neat and consistent, and instead just guestimate things. If the party wants to move into a hex with terrain and encumbrance that would allow for 2 hexes per day, just check if they still have half of the day left. If yes, their camping spot for the night will be in the next hex. If not, it’s going to be in the last hey that they reached. It’s imprecise, but good enough for me.

Random Encounters

I know many people like to check for random encounters in the wilderness once per hex that party moves through, but I found that to actually not make much sense to me. Yes, you are moving through more area when traveling at a faster speed, so there are more spots you pass through where you could encounter something. But you’re also going to spend less time in each spot, which reduces the chances that you are in any one given place just as other creatures are passing through it. I think that just cancels each other out and travel speed does not actually affect the chance of encountering something on a given day. Only the total time spend in the wilderness does.

So I simply roll for random encounters four times per day. Once in the morning, once around noon, once in the afternoon, and then one more check during the night. Regarding which hex a random encounter takes place in, I am again going with “make something up”. If a party is traveling four hexes in a day and a random encounter happens during noon, is it locate in the second hex or the third hex? I don’t know, pick one. It really doesn’t matter.

To check for an encounter, roll a dice that reflects the likelihood of encountering anything in the area the party is traveling through. Going with my paradigm of something always happens on a 1, smaller dice result in more encounters, and larger dice in fewer encounters.

| Encounter Density | Encounter Check Dice |

| Desolate | d10 |

| Sparse | d8 |

| Average | d6 |

| Populated | d4 |

I can totally understand if this system is a bit too abstracted and not granular enough for some people. But I like its neatness in how easy it is for actual use during play, while still overall being somewhat plausible in the distances a party can cover in a day and not diverging too significantly from the distances and durations you’d get with using the exact numbers from the Expert Rules.