As much as I like the D6 system and its approach to space combat, the weapons that they put on the ships for Star Wars are total chaos. Terms are used completely inconsistently even though the stats are generally pretty consistent. About 90% of the time. And then occasionally you run into a gun that has the same range in “space units” as regular other guns of that type but 20 times as much range in “atmosphere units” for no reason at all. Since I am a huge fan of consistency, I made the following list of standard guns found on the vast majority of ships. Continue reading “Unified spaceship weapons for Star Wars d6”

Category: game design

The key to great monster design?

One of my favorite parts about roleplaying game is the creation of new monsters. Sometimes you look at a monster and think “I want to do something just as great”, but since there are already literally thousands of fictional creatures that have been made up by writers in the past 100 years, it always seems very difficult to come up with something that doesn’t look like an almost-copy of something else.

I’ve been looking over a lot of monsters from RPG monster books, videogames, and movies over the last years and found that really outstanding monsters are no accidents. If a monster becomes popular with fans or even a famous part of culture is not entirely up to luck and there are some things they pretty much all have in common and do not actually require being a creative genius.

The first discovery I made is that great monsters are never about their looks or their abilities, but about their behavior. Perhaps let’s call this Yora’s First Law of Monsters: “Monster behavior is more important than appearance or powers.” Yes, the alien from Alien looks really cool and it certainly helps for making it famous, but what makes it so great in the movies is not what it can do, but how it acts. The actual powers are not very interesting at all. It is fast, kills with a bite, and its blood is acid. As monster abilities go, that is very basic and even rather bland. It becomes a great monster because of the way in which the characters of the movies interact with it. It climbs on ceilings, sneaks around silently, and waits in the dark for the perfect opportunity to strike. It doesn’t actually fight very well and is quite easily killed in a direct confrontation. But it doesn’t allow you to face it in a direct confrontation and that’s what makes all the difference.

Going through some Dungeons & Dragons monster books again yesterday, I discovered Yora’s Second Law of Monsters: “Great monsters have a backstory.” With monsters in movies and novels, a great part of the plot is about revealing the story behind the monster and discovering its origin. It’s not very pronounced in Alien, but it’s still there. The eggs in the derilict ship, the dead pilot, the attack on Kane, and the eventual emergence of the alien are all clues that are hinting on the creature to be much more than just a regular alien animal. Someone once transported a whole shipload of those eggs and must have been aware of what they are, but was still unable to contain the threat. That hints at something more going on and that in turn makes the creature itself much more interesting. At the Mountains of Madness introduced two of Lovecrafts most famous creatures, and it’s really all a big mystery story about revealing their parts in a much larger picture. A a counter example, Robert Howard had Conan fight a lot of big dangerous monsters in his stories, but none of them ever really made it big. They are just scary looking things with teeth and slimy tentacles. They work for the stories, but they don’t inspire at all. Worms of the Earth is often mentioned as one of his best stories and the worms work well for the plot, but it doesn’t really seem as if there would be much more to them than that. One creature that Howard created did make it big. The serpentmen from Kull. The yuan ti from Dungeons & Dragons and the naga from Warcraft are among my favorite monsters, but they are really just remakes of Howards serpentmen. Other than taking the shape of humans with the lower body of a snake, they have almost nothing in common with the creature from Asian myth. And what makes the serpentmen different from most other monsters Howard created? They have a backstory. They have goals, they have motivations, and they are integrated in the history of the world.

This seems particularly important to me when creating new monsters for roleplaying games. When you read through monster books, the vast majority of the creatures are just very bland. They have an appearance, some abilities, and very often that is it. Two sentences about the kind of environment in which they live does not suffice to make them cool or interesting. Because there’s no plot hooks in that. What are you supposed to do with a big flying white snake that makes ordinary objects come to life? It has a look, it has powers, but what does it do? When it comes to having players confront a monster in a game, I made the observation that very often reputation makes a huge difference. A telepathic monster that can stun people with its mind might be interesting and challenging to fight. But that’s usually nothing compared to “Holy Shit! It’s a mind flayer! We’re so screwed…” Surprising the players with something completely unexpected is nice sometimes, but just as often you’re getting a lot of excitement if the players are already aware of the creatures reputation. If you create a new creature that is yet unknown, try to put a lot of hints about what it can do and make the other people of the game world be terribly afraid of it. Nobody is going to get super exited about the news that there is a pack of weird critters at the edge of the village that is known as a nuisance. Have the villagers get into a total panic because they have heard many stories about the creature and they don’t believe anyone could possibly save them. That is going to get the players a lot more excited as well.

Idols for Sword & Sorcery BECMI

Reading in the Dungeons & Dragons Rules Cylopedia today, I got reminded of the relics again, which had been introduced in the Companion Set. In B/X and BECMI, only humans can take the cleric and thief classes. All dwarf and halfling characters and NPCs have the abilities of fighters and all elves the abilities of both fighters and magic-users. AD&D made the concession that these demihuman races can have NPC clerics, but in the Basic and Expert sets they have no access to cleric magic at all. To get them access to healing magic and protection against undead, the Companion Set introduced the relics. For the elves, the relic is a Tree of Life, for the dwarves it’s a magic force, and for the halflings a magic fire bowl.

Each relic has a single keeper, who is a regular NPC of that race, but who has access to special powers provided by the relic. He is able to cast spells that heal wounds, cure blindness and disease, neutralize poisons, and identify magic items. In addition to that, the relic is constantly using the Turn Undead ability of a 15th level cleric with a radius of 360 feet. Which is powerful to turn everything except for lichs and instantly destroys everything up to and including vampires. The keeper can use the spells almost unlimited, but every time he does the radius of the Turn Undead area shrinks by 5 feet and only returns by 5 feet per day. So the keeper has a very strong incentive to always try to keep the power of the relic close to its maximum and not cast cure serious wounds on every little bruise.

For my Ancient Lands setting I’ve never been happy with clerics, as their abilities really don’t fit as stand-ins for tribal shamans at all. Keepers are a totally different story though. They recieve their powers from a specifc object tied to a specific place, which serves as a conduit for divine powers. And it has a strong resemblance to many animistic religions and traditions. In the technical terms of antropology, the relics are idols. They are physical objects in which the divine force resides and which priests and worshipers visit in person to communicate with the deity. It is a temporary or permanent home of the deity and in some cases it’s actual body. I belive even in Greek religion it was believed that the deity is actually present in the statue that represents it in its temple. In other places, these idols are natural features, like mountains, springs, or unusual large trees or rocks.

For my Ancient Lands setting I’ve never been happy with clerics, as their abilities really don’t fit as stand-ins for tribal shamans at all. Keepers are a totally different story though. They recieve their powers from a specifc object tied to a specific place, which serves as a conduit for divine powers. And it has a strong resemblance to many animistic religions and traditions. In the technical terms of antropology, the relics are idols. They are physical objects in which the divine force resides and which priests and worshipers visit in person to communicate with the deity. It is a temporary or permanent home of the deity and in some cases it’s actual body. I belive even in Greek religion it was believed that the deity is actually present in the statue that represents it in its temple. In other places, these idols are natural features, like mountains, springs, or unusual large trees or rocks.

In the RC, all elven relics are Trees of Life and all dwarven relics forges, and they all grant the same spells to their keepers. But that really doesn’t have to be that way. Not only can you easily change the appearance of each relic, you can also easily add a few more spells to their reportoire. Also, the Turn Undead effect could be replaced with a different power that is permanently active. The wonderful thing about it is, that it works at every level. It works for a small village shrine that simply has an idol for the spirit of the lake that lies next to it, and you can also have an idol inside a huge temple within a large city, which channels the divine power of the sun to the high priests. By chosing different appearances and powers for each idol, every local cult becomes unique and can have quite different means to protect itself against harm. Instead of a Turn Undead aura, the keeper could be given the ability to raise ring of growth of plants with a 360 feet radius around the idol, to raise and lower an impenetrable wall of briars as it is needed. You could have a shrine in a fortress that constantly puts a bless spell on any defenders on its walls. An a deranged cult that worships a horrific entity from the Underworld might have an idol that utterly defies description. In wilderness locations, an idol could take the form of a magic spring, a waterfall, or a giant tree. Or really anything you can imagine.

I think these idols probably work best if you don’t have any cleric characters at all in the setting. I personally would allow mages to learn cure light wounds as a 2nd level spell and neutralize poison as a 4th level spell, since player characters tend to get into trouble far away from any settlement and you generally don’t want to have the party constantly commuting back and forth during adventures. But any other cleric spells, like restoration, cure blindness, and raise dead, should only be available as miracles granted by the gods if a ritual is performed before their idol. And since most of these gods would just be relatively minor spirits of the land, not even all of them might be able to perform all of these. To raise someone from death, it wouldn’t be out of place to have the party travel to visit the archdruid at the oldest tree in the heart of the forest, or to descent into the Underworld to find an ancient shrine where a powerful demon is being held imprisoned.

Starting at high Hit Points

One peculiar thing about Dungeons & Dragons, and especially in the older editions, is that characters at first and second level are extremely fragile because they have very little hit points and even a single hit by a pretty minor foe can easily lead to instant death, even if the character had been uninjured. A common reason I’ve seen people give for this is the idea of “Zero to Hero”, where you start as an absolute nobody with no skill at all and have to work your way up to become someone. But at some closer examination, that is not really the case. First level fighters are already elite warriors who are standing well above all regular soldiers, mercenaries, bandits, and other professional full-time warriors, many of which have been at that job for years or decades. Except for commanders, all soldiers in B/X or AD&D are simply “Normal Men” or “0 level men-at-atms”. A first level fighter has a better chance to hit, better saving throws, and also has a Constitution score that can get him additional hit points. You’re not a nobody, you’re already starting as someone who has come farther than all regular people will ever get.

As characters go from 1st to 2nd level, their average hit points double, and depending on how your dice fell, they might even tripple. Yet enemies are still dealing pretty much the same damage, so that is a huge jump in your odds to survive. In some recent games, like Barbarians of Lemuria, Dragon Age, and Atlantis, hit points for starting characters are handled quite differently. You start at a pretty decent number but then increase your maximum number of hit points only at a relatively modest pace. I wonder how that would change D&D?

One simple idea would be to reduce the type of hit die by one step for each class and then give all characters a number of bonus hit points equal to twice the maximum hit die result. An AD&D thief would start with 8+1d4 hp (9-12) instead of 1d6 hp (1-6) and a figher with 16+1d8 hp (17-24) instead of 1d10 hp (1-10). If you leave the amount of damage dealt by enemies unchanged this should change gameplay at lower levels quite significantly. Ignoring healing spells and potions (which 1st level parties would have almost no access to), staying power would increase about an average of four times. As you go to higher levels, that initial boost becomes increasingly less significant and you probably wouldn’t notice the difference between 9d10 hp (average 50) and 9d8+16 hp (average 56). If survival at low levels becomes significantly easier and groups can take on much larger numbers of enemies, but you got almost no difference at higher levels, it also quite likely would change the perception of how high-level play becomes either easier or harder.

However, that would mean that 1st level characters are able to deal with much larger numbers of low-level monsters at once, and I am not sure if I’d want them to be that heroic. One solution would be to also give all the monsters bonus hit points. Perhaps equal to the maximum result of one hit die (8). That would mean one on one fights are unlikely to end at the first hit and usually take two or three to win. This would be closer to what the games I mentioned above are doing.

I’d really like to try that out and see what happens.

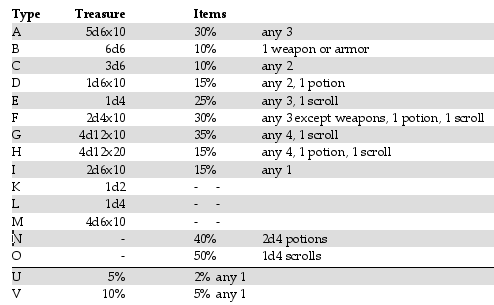

Simple Treasure table for B/X

While I am generally a fan of having characters gain experience based not only on the amount of enemies they defeat in battle but also on how many treasures they retrieved during the adventure, dealing with individual gold pieces always seemed too fiddly to me.

My preffered way to handle treasure both in regard to wealth and encumbrance is to use a simple unit of “1 treasure”. As long as characters still have 1 treasure, they can buy any items and services of trivial costs, such as food, drink, a room in an inn, most weapons, and so on. Anything that is too expensive for most common people to affort cost 1 treasure, such as a horse, chainmal armor, or a boat. As a rule of thumb, every treasure is worth about 100 gold pieces and can consists either of a bag of coins, a large golden cup, a crown, or whatever else the GM wants to describe it like. It also counts as 1 item for calculating encumbrance. (A character carrying items numbering up to their Strength score are unencumbred and can carry twice as much being lightly encumbred and three times as much being heavily encumbred.)

The treasure tables in the Basic and Expert sets of Dungeons & Dragons give various chances and amounts for different types of coins and gems, so using this alternative treasure system while retaining the same rate of experience gain requires some conversion work.

Which I did. Here’s the result.

Type J and type P to S are not on this table as their average results are way below 100 gp.

Type J and type P to S are not on this table as their average results are way below 100 gp.

Why so little love for Group Initiative?

Among the many great things of Basic D&D, one that stands out the most for me is the initiative system. I find it so much better than the commonly used by other editions and even most B/X clones.

A wonderful thing about group initiative is that it completely removes the whole work of remembering the initiative order. I absolutely hate it to scribble down a list of all the PCs and enemies in the correct order at the beginning of each fight. That’s always a minute or so of interruption doing something tedious, right at the most exciting moment of the game. The alternative is to write down the names in advance and make a row of numbers with the initiative counts, but then you easily skip someone by accident all the time. (At least I do.) With group initiative that doesn’t matter. You roll two d6 at the beginning of each round and then everyone goes in whatever order they want.

But I think something even much more important is happening on the player side. Everyone is paying attention all the time and taking turns much faster. Nobody is sitting around three numbers until their number comes up.

The players who decide the fastest what they want to do go first, and those who take longer do their thinking while everyone else is taking their turn. And everyone needs to pay attention during the whole enemy turn, because the next turn is always their turn.

I’ve been using this system for a while, and it’s just so much more fun to run the game, and I believe for the players as well. Why doesn’t everyone use it and most games go with individual initiative counts instead? Even such otherwise great games as Basic Fantasy and Lamentations of the Flame Princess and wonderful ones like Spears of the Dawn and Barbarians of Lemuria (not a B/X clone, but still) go with the cumbersome initiative count system. Which to me really has always been one of the most annoying thing about running games.