With my work on the Ancient Lands I have fully embraced the paradigm that perfection is reached not when there’s nothing left to add, but nothing left to take away. And there’s always more stuff that still hangs around because I like the idea but that doesn’t really contribute to the overall quality of the setting. This is not just geographical content and world lore, but also a lot of small changes and custom additions to the rules and mechanics of B/X D&D. Some of them might actually be really good ideas, but who is really going to care? Those people who would care are most likely people who make their own extensive custom changes to the rules and the most likely to not use any material the way I have written it. And what am I really trying to sell to people? It’s not a game, it’s a world.

I think cramming too much custom rules into a setting is to be following in the steps of the Fantasy Hearbreakers from the late 70s and early 80s. They were attempts by people to make and release their own RPGs that are largely like D&D but with some improvements. Some of them might even have been quite good, but who cares? People already had thei D&D and you have to offer them something substantially different to get them to switch. It’s easier with the new options of publishing today and Kevin Crawford seems to be doing just fine with his work, but I really don’t think that there is much interest in small obscure settings with their own unique rules. But it’s going to look much more promising when you turn to settings to be used with the rules people are already using.

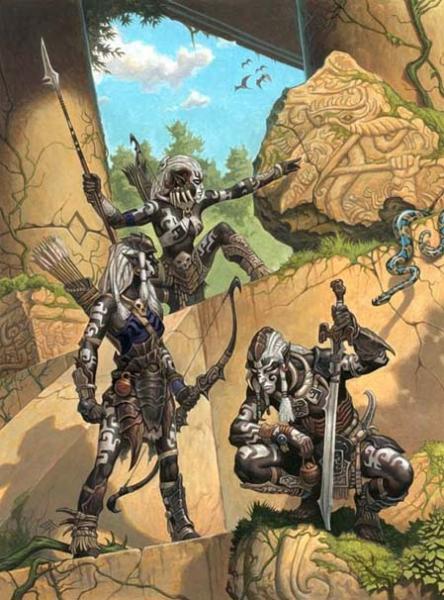

Some while back I mentionee working on an alternative magic system, but I’ve now decided to not pursue it any further. At least for now. The Ancient Lands are a world to be used with the rules of D&D, but not written for D&D. While I like the mechanics f B/X, I am not actually a fan of the type of settings that follow from putting the content described in the rulebooks into practice. I already replaced the vast majority of character races and creatures with my own creations and the world is written with a soft cap of 9th level for characters. (You could play at higher levels but it’s assumed that the number of such people in the world is negible.) When it comes to spells, I have decided to give the setting its own identity by simply stripping away everything from the rules that doesn’t fit. D&D magic has long been designed to offer any kind of spell players could think of so they would be able to play any kind of spellcaster they’ve seen in fiction. While this is part of the reason why magic becomes so (over)powerful at higher levels, it’s actually very convenient in this case. For all the things I want magic to do in my setting, there are already spells available. So I created the following spell list to be used wit the magic-user class.

- 1st Level: charm animal, detect magic, entangle, light/darkness, message, remove/cause fear, resist cold, sleep.

- 2nd Level: charm person, detect invisible, ESP, invisibility, obscure, resist fire, speak with animals, web.

- 3rd Level: dispel magic, growth of animals, gust of wind, hold person, infravision, produce fire, suggestion, water breathing.

- 4th Level: charm monster, fear, growth of plants, polymorph other, polymorph self, remove/bestow curse, speak with plants, wall of fire.

- 5th Level: animate dead, dispel evil, hold monster, insect plague, stone shape, wall of stone.

As some might have spoted, there is no direct damage, no free information gathering, no teleportation, and no healing. As I already mentioned in previous posts, healing is the domain of spirits and potions. Helpful spirits might be encountered in the wild and be persuaded to provide healing, but usually the right adress for magical healing is a village shrine where the shaman can channel the healing powers of the local god that watches over the settlement. In my last three campaigns the party did just fine by relying only on healing potions and not having any cleric around. It really depends on how generous the GM is with these being found on overpowered enemies and in treasure coffers.

This came as a bit of a surprise to me. Even though they are all D&D, there’s a huge number of major differences between the various editions. The most common reason I’ve seen discussed for 3rd edition being bad at high level play is that wizards got more spells per day and lost most of the limitations and weaknesses they had in AD&D. But that alone can’t be reason if the problem goes back all the way to the mid 70s.

This came as a bit of a surprise to me. Even though they are all D&D, there’s a huge number of major differences between the various editions. The most common reason I’ve seen discussed for 3rd edition being bad at high level play is that wizards got more spells per day and lost most of the limitations and weaknesses they had in AD&D. But that alone can’t be reason if the problem goes back all the way to the mid 70s.