I decided that for Lore 24, I will be going with my Kaendor setting again. While I’ve been working with it for years and even ran a few short campaigns in it, the vast majority of that campaign setting exist only as very short mental notes in my head. Barely anything is actually spelled out about its current incarnation, and the parts that do exist are mostly rather vague and remaining at the stage of an idea outline. Lore 24 seems to be the perfect opportunity to turn those ideas and impressions in my mind into actual, concrete setting material.

While my current vision of Kaendor has a surface appearance that is deliberately a fairly generic elfgame Fantasyland, it also has some pretty major divergences. Whose gradual discovery by the PCs as they leave the familiar grounds of civilization is meant to be the central theme and core concept of the campaign setting. I feel that many of the things I want to write down for Lore 24 won’t be able to be really appreciated without any context for the world that they are meant to exist in. And so I want to use this post to provide a general, top level overview of the world, covering the main parameter that are already fairly set in stone.

Since I got a lot of ideas for a new campaign set in Kandor from several D&D 3rd edition books, it seems the most sensible approach to me to simply plan this out as a 3rd edition campaign. A large number of things I want to have in this world already exist in game terms for this system, and it is a game that I am very familiar with and feel very confident with for creating new creature abilities, spells, and unique mechanics.

Shadows of Kaendor is written as a setting for a D&D 3rd edition campaign covering 1st to 10th level, that also is home to a few NPCs up to 12th level. It uses the following books for character creation and advancement options, and for optional rules and mechanics:

Shadows of Kaendor is written as a setting for a D&D 3rd edition campaign covering 1st to 10th level, that also is home to a few NPCs up to 12th level. It uses the following books for character creation and advancement options, and for optional rules and mechanics:

- Player’s Handbook

- Expanded Psionics Handbook

- Manual of the Planes

- Monster Manual

- Monsters of Faerun

- Lords of Madness

Other influences and inspirations are taken from the AD&D adventure The Forgotten Temple of Tharizdun, and from Bloodborne, Thief, and Hollow Knight, which should become apparent further below.

The continent of Kaendor is populated by the following peoples, using the creature stats in the brackets (PC options in bold):

- Snow People (high elf)

- Fog People (wood elf)

- Forest People (high elf)

- Mountain People (goliath)

- Coast People (gray elf)

- Sea People (aquatic elf)

- Plains People (half-elf)

- Chitines

- Gnolls

- Goblins

- Grimlocks

- Locathah (amphibious)

- Ogers

- Quaggoths

- Wind People (avariel)

Player characters and NPCs can be of the following classes:

- Barbarian

- Cleric

- Cloistered Cleric

- Druid

- Fighter

- Psion (psionic)

- Ranger

- Rogue

- Wilder (psionic)

- Wizard

There will be no prestige classes in the campaign.

Unlike most D&D settings, the world consists of only a small number of planes:

- Material Plane.

- Plane of Faerie, the realm of fey and elementals.

- Plane of Shadow. (Also covers all the functions of the Ethereal Plane.)

- Unknown Planes beyond the Shadow, the realms of aberrations.

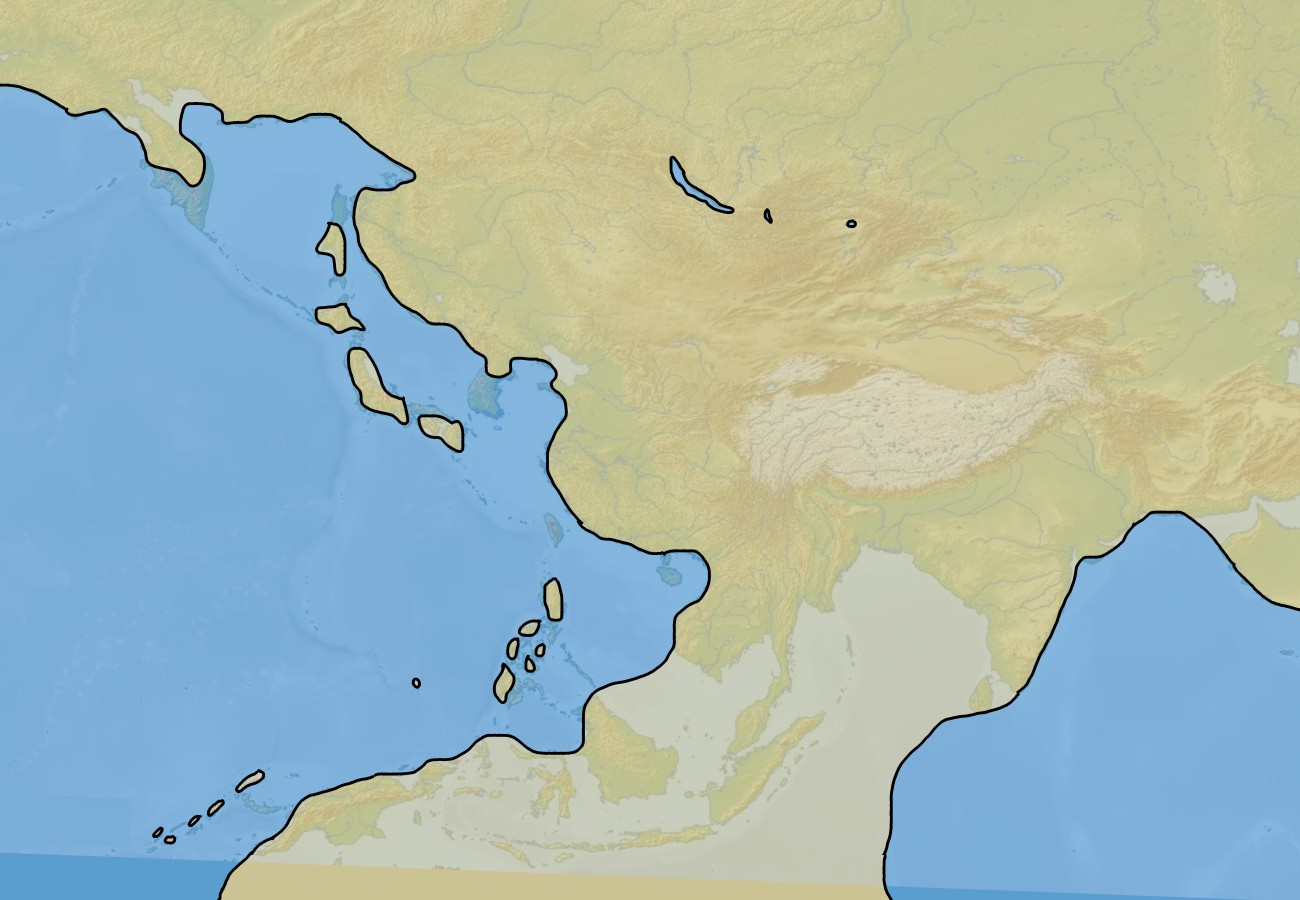

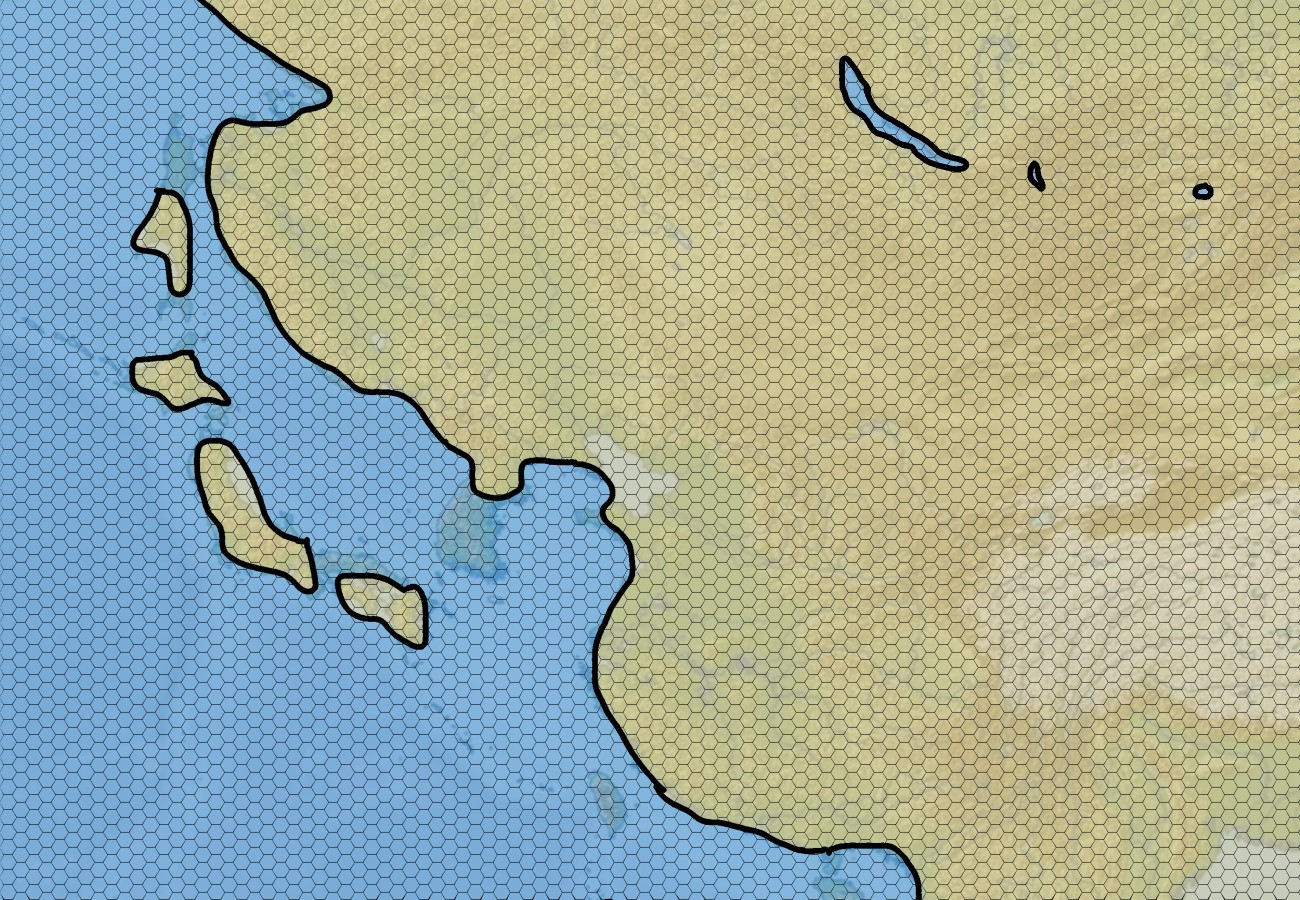

Kaendor is a large coastal region that ranges from Mediterranean climate in the south to sub-arctic in the north. Its civilization is fairly young and accordingly only very sparsely populated. The society and technology is roughly oriented towards the very early Middle Ages. at the end of the Migrtation Period in the 6th and 7th century. Weapons and armor are dominated by one handed swords and axes, spears, bows, chainmail shirts, simple helmets, and round wooden shields. Architecture is very Romanesque in style. In many ways, society has much more resemblance with the images of Celtic and Viking culture than the large kingdoms of the High Middle Ages, though there are a number of fairly powerful and sophisticated coastal city states.

Most larger towns have a low level adept as their priest or shaman, with clerics mostly found in the great temples of the major cities. Wizards are not exactly common, but in most places the locals will be able to give directions to at least one wizard within two or three days’ walk that they have heard of. The vast majority of NPCs are 1st to 6th level, with those of higher level invariably being people of some fame beyond their immediate community.

Shadows of Kaendor does not use sorcerers (or bards). Instead the role of these spellcasters is being filled by Wilders. These are rare people with a special gift that allows them to peer through the surface of the world and gaze at the true nature of reality, enabling them to master doing, seeing, and knowing certain things that should be impossible. To most people these powers seem like magic, but the truth is far more complex and far reaching than that. Psions are scholars who have learned of these occult truth, and through study and meditation have gained access and far greater understanding of these powers that come to wilders naturally. While wilders, and also psions, have been around for a very long time, most people who encounter their powers are mistaken them for magic spells, including even many wizards.

Instead of the much more common sorcerers and demons from a hellish realm of fire that take the role of the supernatural forces of evil, this aspect of Kaendor is occupied by eldritch aberrations that have long been forgotten in the eternal darkness beyond the borders of this world. Exploring these aspects of the setting will obviously lead into the dark and creepy, but Shadows of Kaendor is not meant to turn into a gory horror campaign of bleak despair. It’s still meant to be a world where adventuring heroes can drive back the strange terrors they face off against and emerge from the darkness victories.

Though safety is not guaranteed.