- Old-School Essentials Sword & Sorcery West Marches campaign set in Kaendor, exploring the ancient ruins of the northern forests which have only recently begun to being settled by groups of people fleeing the reach of the sorcerer kings in the south.

- Iridium Moons: Coriolis homebrew Space Opera campaign about two merchant cartels fighting over who is going to have a monopoly on trade after the last large mining company pulls out of the sector, and their attempts to make the many small independent mines completely economically dependent on them.

- Shadows of the Sith Empire: A Star Wars d6 campaign set after the Dark Side ending of Knights of the Old Republic, in which a new Sith Empress controls a quarter of the Old Republic’s systems and is sending her agents out to search for lost ancient Sith texts that hold the secret of how Marka Ragnos and his predecessors managed to hold their empire together and how she might prevent her own apprentices from inevitably turning against her.

- The Outer Rim: A Star Wars d6 campaign set right after the destruction of the Death Star at the height of the Empire’s power. The party consists of former senatorial aides and guards and imperial officers who have fled to hide in the Outer Rim among the smugglers, scoundrels, and gamblers to escape the purges in the core worlds. Meanwhile the new Moff of Enarc has decided to establish order in the space between Sullust and Tatooine by putting an end to the fighting over spice smuggling between the Hutts and Black Sun. Imperial crackdowns and increased fighting between the two syndicates to be the one that gets to keep the region for itself only increases the chaos and raises sympathy for a rebellion against the empire.

- The Heart of Darkness: Dungeons & Dragons Planescape campaign that focuses on the rarely visited planes Beastlands, Ysgard, Pandemonium, Carceri, and Gehenna and revolving around an arcanaloth, a rogue asura with an army of Fated, the Revolutionary League, and the Doomguard trying to gain control over a terrible artifact of entropy.

- Murky Waters: A Mutant: Year Zero campaign set in the islands that are left of Denmark, Northern Germany, Northern Poland, and Southern Sweden after an 80m sea level rise. The mainland is completely uninhabitable by clouds of deadly fungus spores, but the salt of sea water keeps the fungus from taking hold on small islands in the stormy sea.

- Sankt Pauli bei Nacht: Vampire campaign set in Hamburg, with a brewing conflict between old Ventrue shipping magnates and Bruja activists over which neighborhoods are their rightful territory as gentrification changes the social environment. With Malkavians claiming the rowdy entertainment district in the harbor, and a gang of Nosferatu the subway systems. And going all the way back to the concepts of the first edition, it’s actually going to be personal horror.

Category: Star Wars

The role of PC Heroes in Star Wars

While I am working on my Hyperspace Opera setting, I am frequently getting out various Star Wars RPG books to look for ideas. And unsurprisingly, it’s always just a matter of time until I start to think “Man, I should run a d6 Star Wars campaign in the meantime.” It’s Star Wars! It’s amazing!

But then I grab something to take some notes and start looking for ideas what the campaign could be about, and where and when it would be set, and the whole thing begins to lose traction really rapidly. The main reference for what Star Wars is and what makes Star Wars cool are the adventures of Luke, Han, Leia, Chewbacca, and Lando. They quickly turn out to be major movers and shakers, destroying the two Death Stars, having several encounters with Darth Vader, and being directly responsible for facilitating the death of the Emperor. Their interactions with the setting and the major power players within it, and their perspective on the world as a whole are very different from what a group of freshly made PCs could ever experience.

But why does that have to be?

It is convention in RPGs that a party of new PCs consists of people with no significant accomplishments who are each just one out of a thousand or even a million of similar people with similar aspirations. They are bit players and peons, who through their deeds can slowly grow in strength and make connections to possibly one day become important actors in the fate of their worlds. And this works great for a great range of games, settings, and campaigns. But for a Star Wars game, this just doesn’t hook me. Playing rebel grunts ambushing imperial patrols to steal a crate of blasters, or irrelevant cargo pilots who have a rival crew trying to steal their cargo doesn’t really capture any of the things that make Star Wars amazing.

So instead of having a party of fresh new characters who first arrive on the scene at the start of the campaign and then look on the big picture from far below, why not have the players play PCs who are capital H Heroes? We have established that the Emperor and Vader killed all the Jedi except for two, but in that big galaxy, there could very well be a third who is also out fighting the Empire on his own in a complete different region. When we meet Han and Lando for the first time, they are not ordinary scoundrels. They both have reputation and influence that indicates they are pretty big shots in the circles they associate with. And Leia is an imperial senator and appears to be at least in the second tier of the leadership of the whole Rebel Alliance. Luke really is the very notable exception here, and that’s because he’s the main point of view character for the first movie. By the second movie, his role has already changed completely.

So instead of having a party of fresh new characters who first arrive on the scene at the start of the campaign and then look on the big picture from far below, why not have the players play PCs who are capital H Heroes? We have established that the Emperor and Vader killed all the Jedi except for two, but in that big galaxy, there could very well be a third who is also out fighting the Empire on his own in a complete different region. When we meet Han and Lando for the first time, they are not ordinary scoundrels. They both have reputation and influence that indicates they are pretty big shots in the circles they associate with. And Leia is an imperial senator and appears to be at least in the second tier of the leadership of the whole Rebel Alliance. Luke really is the very notable exception here, and that’s because he’s the main point of view character for the first movie. By the second movie, his role has already changed completely.

This idea is certainly not new, but it has never occured to me. PCs in a Star Wars campaign don’t have to be extras in the story of the Rebellion against the Empire. They absolutely can be protagonists in a story just as big as the one of Luke and Vader.

Search your feelings! You know it to be true.

Using the Gambling skill

I’ve recently been part of a discussion about rarely used skills in Star Wars campaigns. Gambling in particular seems like a skill that has little actual use for players and that is difficult for GMs to work into adventures in a meaningful way.

In this case, I think the burden of making the skill useful really does fall primarily to the player. You chose to invest points into the gambling skill, or to take gambler as your character archetype. Of course it is good form for the GM to be accommodating and make an effort to allow players to play to their characters’ strengths. But when you want to play a gambler, or any other character with a focus outside the typical adventure activities for the setting or genre, it falls to you to come up with an idea how it will be part of the campaign.

In this case, I think the burden of making the skill useful really does fall primarily to the player. You chose to invest points into the gambling skill, or to take gambler as your character archetype. Of course it is good form for the GM to be accommodating and make an effort to allow players to play to their characters’ strengths. But when you want to play a gambler, or any other character with a focus outside the typical adventure activities for the setting or genre, it falls to you to come up with an idea how it will be part of the campaign.

While I don’t have the slightest idea how to make use of basket weaving in an adventure campaign, I do see quite a number of options of how you can make gambling a meaningful part of a Star Wars campaign, and to some extend in RPGs in general.

When you think of the main purpose of gambling, making money is the obvious answer. But in a Star Wars game, money generally does not play a meaningful role, as all the equipment you really need is a blaster for every character and a small ship for the whole party, which you often get at a very early point of the campaign. It’s not a setting where characters are constantly upgrading their equipment with potato peelers +2 or you have a dozen types of increasingly protective and expensive suits of armor. Like in Sword & Sorcery fantasy, money appears as something much more abstract within the stories, really only mattering when the characters are faced with a massive debt or huge expense that will be impossible to cover unless they take on that one suspiciously well paying job or find the fabled treasure of legend. The need for large amounts of money is an adventure hook, an excuse to get the players to go to a place where the GM has something prepared for them. And in that case it’s in nobody’s interest to have some characters spend a whole session in a casino and play 50 rounds of cards. Which is why the amount of money you can make with gambling or picking pockets is usually trivially low.

My suggestion is forget about money. Don’t go gambling to get rich as a simpler (and boring) alternative to go on an adventure. What really makes gambling interesting from a story perspective are the debts that result from it. When you play a gambler, or any character with a high gambling skill, try to get into games with imperial officers and gang leaders and get them into debt. Because debt means leverage.

This is one of the cases where the GM has to be accommodating. The GM can always say that the NPC in question does not gamble, doesn’t play with the PCs, stops playing when the credits run out, or has the necessary money at hand to pay the debt. But I think when you approach the GM with a plan to try manipulating an NPC through gambling debts, most GMs will be quite happy to give you a chance in at least some situations. It doesn’t make sense for all NPCs and in all situations, but this is just the kind of creative problem solving that I always love to see from players, and which makes running games the most fun.

When you have an NPC in debt, you can have the leverage to either get information or a favor. Have the NPCs tell you about other people you are really after or about places you want to get into, or ask them to do small things that will greatly help you overcoming some obstacles for your big plan. Getting you access keys, disabling alarms, planting bugs, distracting guards, that kind of thing.

But as it says in the name, gambling is always a gamble, and there’s always a real chance that even a master gambler fails and ends up being the one losing a lot of money. Which ultimately can lead to the player ending up in deep debt to important and influential people. Which from a narrative perspective is awesome! We get to increase the tension for the current adventure and have the players facing even more obstacles than they did before, and they all know perfectly well that it’s purely the result of their own actions. These are the best kinds of consequences and a fantastic example of failing forward.

Another way in which gambling can be useful is simply as a cover while spying on NPCs or checking out places. When you’re sitting at a table loosing great amount of credits (or winning them), nobody is suspecting you to be in the place for other insidious reasons. Gambling is a nice way to get NPCs into conversations and to make them let their guard down by either separating them from their credits or making them enjoy a winning streak. The richest and most powerful people usually tend to play in places where the stakes are very high, and being very good at gambling is a classic trait of various villainous archetypes. You might be able to get a simple customs officer or low ranking gangster into a low stakes game in some cheap cantina, but when you want to go against crime bosses and moffs, you have to be able to play with the pros. Both in skill and the money you bring to the table. So as your gambling skill increases, you don’t just improve your chances of success, but also gain access to more influential and important people.

There doesn’t seem to be any obstacles in a typical adventure that your character can overcome by making a gambling check. And while it may look like a way to make some easy money at the side, like you can do with picking pockets and cracking safes, you really should think of it more as a skill to help you get access to information and objects that are not easily available otherwise. More than anything else, gambling is a social skill. When you approach it like this, the potential situations in which it can win the day broaden considerably.

Star Wars Gamemaster Handbook – A book that teaches gamemastering

The Star Wars Roleplaying Game by West End Games was first released in 1987, four years after Return of the Jedi had been in theaters. It got a second edition in 1992, which this time also included a Gamemaster Handbook that was released in 1993. This was 14 years after the first Dungeon Master’s Guide for AD&D 1st edition, and 2 years after the 2nd edition DMG. At the same time, Shadowrun had been around for four years, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay for seven, and Call of Cthulhu for twelve, so it really wasn’t entering into any completely unknown territory.

While I can’t really say anything about the later games, I am quite familiar with all the Dungeon Master’s Guides other than 4th edition, as well as the GM sections for a dozen or so retroclones based on B/X and AD&D 1st ed. But when I managed to get my hands on the Star Wars Gamemaster Handbook and read it, I discovered something that seemed amazing:

The Star Wars Gamemaster Handbook tells you how to be a Gamemaster!

“Well, duh!” you say? “That’s obviously what a gamemaster book is for.” Well, it should be obvious, but when you look at what passes as Dungeon Master’s Guides in D&D, it really isn’t. In the many editions I had both on the internet and with the players of my D&D 5th edition campaign (most of who have much more experience with it than I do), people regularly bring up how 5th edition is really unclear on how you’re supposed to actually run the game because it seems to assume that you run narrative-driven campaigns but all it’s rules are for dungeon crawling. Particularly older GMs express that the 5th edition DMG fails to even mention such basic things like how you make a map for a dungeon and fill it with content.

But this isn’t really a new thing. Since the very beginning, D&D has always assumed that GMs already know anything there is to preparing adventures and running the game, and all the GM content in the books consists of optional mechanics, lists to roll for randomly generated content, and magic items. What are you supposed to do with those to run an enjoyable game for new players? “Well, it’s obvious. Isn’t it.” But no, it isn’t.

The Star Wars Gamemaster Handbook is the complete opposite. It’s 126 pages and except for the example adventure that makes up the last 21 pages, there is a grand total of two stat blocks! Both as examples for the section that guides you through the process of creating named NPCs and translating them into game terms. Which don’t even take up one page in the twelve page chapter dedicated to this topic.

- Chapter 1: Beginning Adventures, 10 pages, gives an overview of the process of coming up with adventure ideas and turning them into playable content that has some narrative structure to it.

- Chapter 2: The Star Wars Adventure, 11 pages, expands on the previous chapter and goes into more detail about making full use of the unique setting and capturing the tone, pacing, and dynamics of Star Wars in a game.

- Chapter 3: Setting, 11 pages, has great advice on using places and characters from the movies or creating your own material, with a focus on explaining what kind of elements you actually need to prepare, what is irrelevant, and the reason for it.

- Chapter 4: Gamemaster Character, 12 pages, is all about thinking of NPCs as people first, and imagining them in ways that are memorable and makes them relevant to the events of the adventures and campaigns as individuals, and how to use them during actual play. Creating stat blocks for them is only a minor subject at the end of the chapter.

- Chapter 5: Encounters, 13 pages, deals with encounters primarily as social interactions and what purpose individual encounters could serve to further the development of the narrative. There are a few sections on selecting the right amounts of hostiles for encounters that could turn violent, but it manages to do so without using any tables or stats.

- Chapter 6: Equipment and Artifacts, 11 pages, is all about gear and related stuff, but doesn’t include any stats for specific items. It’s a chapter about resources that can be made available to PCs and NPCs and how they can drive the developing narrative of adventures as they unfold.

- Chapter 7: Props, 7 pages, is about handouts and maps and the like.

- Chapter 8: Improvisation, 8 pages, explains in simple and easy to understandable terms the concepts of prepared improvisation, or the art of equipping yourself with the tools you’re likely going to need to quickly address completely unplanned situations on the fly.

- Chapter 9: Campaigns, 9 pages, lays out some basic ideas of running games for a long time through multiple adventures, in many ways approaching it from a perspective of sandboxing.

- Chapter 10: Adventure “Tales of the Smoking Blaster”, 17 pages, is a simple adventure consisting of four episodes that shows how all the principles from the rest of the book could look like in practice.

To be fair, none of the things I’ve read in this book are seemed in any way new to me. I knew all of this before, and it doesn’t go very deeply into detail. But it took me 20 years to learn these things on my own and soaking up the wisdom of several dozens old-hand D&D GMs. And here it is, black and white on paper, spelled out in simple terms that are very much accessible to people completely new to RPGs, in a 27 year old book!

Now I am not a dungeon crawling GM. I am not a tactical fantasy wargame GM either. And there are different goals and requirements for different types of campaigns. But I feel that this is hands down the best GM book I’ve ever come across. It even beats Kevin Crawford’s Red Tide and Spears of the Dawn. They are very impressive books in their own right and do a great job at explaining the practices of sandbox settings in a D&D context. But they also fail to mention most of the information that is in the Gamemaster Handbook, like how you run NPCs as people and set up encounters to be interesting and memorable, apparently assuming that these things are obvious and already known. Like all other D&D books on gamemastering.

I think for most people reading this, there won’t be much new or particularly enlightening in this book either. But I think when any of us are asked by people who are new to RPGs (or maybe not) and first want to try their hand at being GMs but have no idea where to start, I think this book is still very much worth a huge recommendation. Not just for Star Wars, but for all RPGs in general. All the things that are laid out in this book would be really useful to know even when you want to run an OD&D dungeon crawl.

This book is fantastic, because it’s the only GM book I know that really teaches you how to be a GM instead of telling you about additional mechanics not included in the main rulebook. If my favorite RPG posters all got together to put together a guidebook on how to actually run games in basic and easy to understand terms, I don’t think I’d expect anything to be in it that isn’t already in the Gamemaster Handbook for the Star Wars Roleplaying Game 2nd edition from 1993.

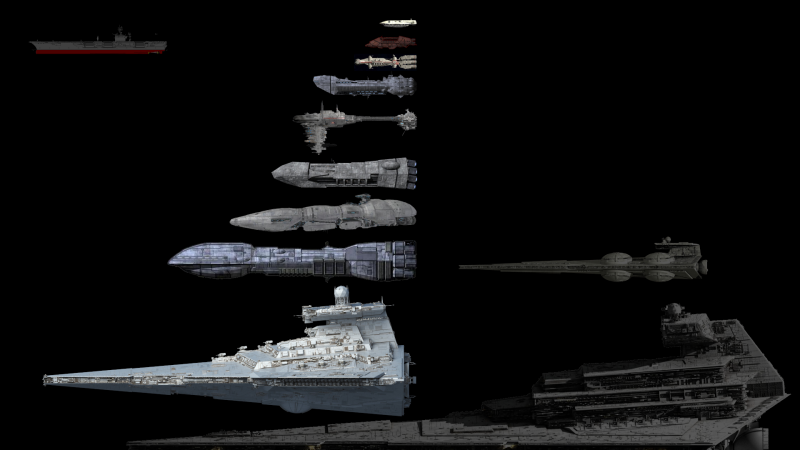

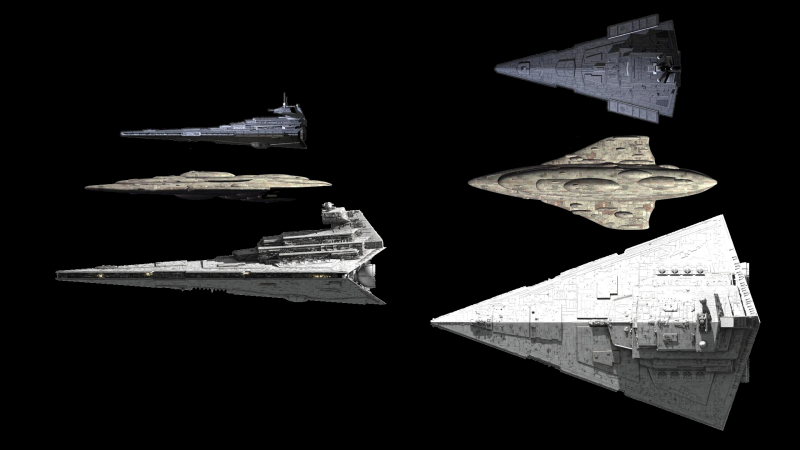

Star Destroyers are big!

Yes, of course they are big. Everyone knows they are big. That’s their thing.

But in the movies we only ever see one of them next to a Corellian Corvette, which is one of the very smallest ships that is still considered in the capital ship category. A number of additional capital ships have become well established in the Expanded Universe over the decades, each with their own listed lengths. But seeing the numbers on paper usually does not really give a true sense of the relative sizes. A ship that is twice as long as another ship of the same shape is not twice as big in total mass and volume, but eight times as big.

To better visualize this I took images of the various ships that make the most frequent appearances and put them together side by side at the same scale. And it turns out, Star Destroyers are really big.

In the movies, the Imperial Star Destroyers are simply very big, with no real reference to how they compare to other large warships. But against the most common ship types of the Expanded Universe, they are still absolutely massive. There really isn’t anything in their weight class except for the occasional obscure one-off appearances.

Because the Mon Calamari MC80 cruisers are over a thousand meters long, I always had assumed that they are comparable to Imperial Star Destroyers. But seeing them side by side that really is not the case. The MC80 is actually most comparable to the Victory Star Destroyer, which is usually seen as the miniature version of the Imperial Star Destroyer.

And again, the Victory Star Destroyer is not a small ship itself. It is still absolutely enormous. When Dreadnoughts were introduced in the Expanded Universe, they were usually portrayed in a way that made them seem like extremely large and powerful ships, or at the very least would have been during the Clone Wars. Apparently the biggest ships the Old Republic had in its fleet. But at 600 meters in length and with a relatively narrow shape, they are already dwarfed by a Victory Star Destroyer and appear almost tiny next to an Imperial Star Destroyer.

When I create stuff for Star Wars, I always try to take the three movies at face value, taking them as my reference frame for what the Star Wars universe is by default. But in light of this comparison, sending four Imperial Star Destroyers into an asteroid field to chase the Millennium Falcon was absolute overkill. And as much as it pains me as someone who regards The Empire Strikes Back as the best movie ever made, the Super Star Destroyer was just stupid.

When it comes to having Imperial ships make appearances in Star Wars adventures, I think Star Destroyers should be reserved for scenes of particular significance. Using them as the go to Imperial warship for most common space encounters lessens the impact their incredible size and power can have. The appearance of Star Destroyers near a planet where the heroes are on a mission, even a Victory Destroyer, can be used as a very effective signal that the stakes have been raised well above normal. Because when there’s a Star Destroyer, there’s always a huge number of TIE Fighters, and even larger numbers of Stormtroopers that could be on the ground. A Star Destroyer is a threat you can not really fight. Your only options are to try to hide or to run. But unless you have a huge fleet on your side, you’re not going to defeat it in battle. And if you manage to get on board of one to sabotage it, your only hope is to evade the thousands of Stormtroopers. You’re not going to defeat them and capture the ship.

It’s just too damn big!