A few weeks back, Joseph had been writing about the idea of having parties going on adventures only for some months of the year when weather permits it and then returning for the winter to deal with business back home. It’s an idea that goes back at least as far as Pendragon, but also more recently appeared in The One Ring. And in both cases it seems to be an element that is quite popular with players and that constitutes a pretty important part in giving these games their unique spin. It basically has to main effects on a campaign.

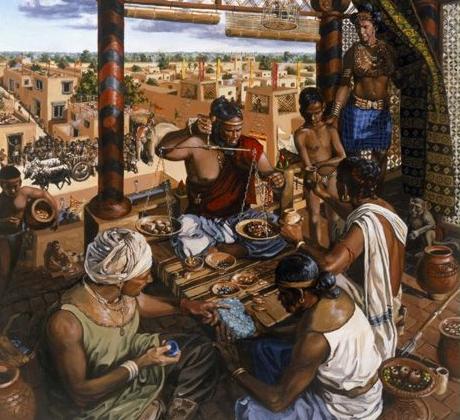

One is that players have to regularly return to a safe haven for overwintering, which can nudge players to get involved in more urban or social adventures which they normally wouldn’t seek out. It also allows for a good blend of exploration adventures and domain management if that later aspect is desired.

The other thing that it does is to create a much stronger sense of the passing of time. One oddity of megadungeons, super-modules, adventure paths, and other kinds of published campaigns is that they often take characters from first level to high levels at an incredibly fast pace. Often just a couple of weeks or a few months at the most. After which they are as powerful and experienced as NPCs who have been at it for decades or even centuries. Even if the campaign includes time jumps like “after 5 weeks of sailing” or “several months later”, these things don’t tend to be felt by the players, to whom it might just as well have been “later that afternoon”. By regularly alternating between adventuring season and winter camp, you at least communicate the idea that the campaign stretches over a couple of years.

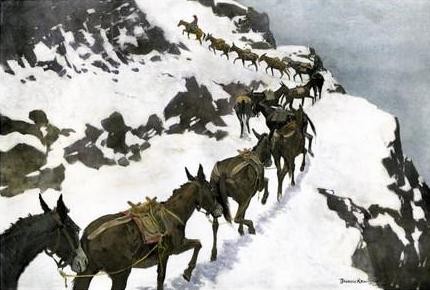

To add this aspect to your game, you don’t actually need any specific rules for it. All you really need to do is track the passing of days on the calendar. Even if it’s just a simple campaign of going to the dungeon and poking around, placing the dungeon a few days travel from the next village and putting each village with a dungeon a week or two apart from each other will lead to a lot of time passing between each session. If you have a sandbox (one that isn’t about filling out a 6-mile hex map), put the various locations a good distance away from each other and players should very quickly rack up pretty long travel times. Once the campaign reaches the end of the ninth or tenth month, simply tell the players that weather is getting increasingly awful for camping in the wilderness and that they should find a place to stay until the fourth month or so.

If it fits the campaign, you can then simply jump ahead to the next spring and continue from there. There are also a good number of great adventures that can be had during the winter. But these are usually not long expeditions into the wilderness. Much more commonly these are things with isolated villages being threatened and no help coming until spring. The kind of places where you would expect adventurers to stay for the winter. These don’t have to be elaborate adventurers. They can easily be just simple one-shots for a single session, but can also be pretty big things as well. The advantage of this is that you will have the players remember that they actually have experienced a winter and it’s not something that was only mentioned once in passing. For my Ancient Lands campaign, I am planning to make a simple Random Event table, on which I will make one roll for every month in winter camp. With a 1/6 chance four times in a row, something is almost certainly to happen; perhaps even two things. These would probably have to be rolled in advance and not at the table, so you can prepare some material for it. But again, it doesn’t have to be big things. “Frozen Zombies” or “Winter Wolves” would be enough as a hook for the GM. Then you can start with destroyed farms or dead cattle in a stable and have the players deal with it as you usually would in a sandbox. Since the players are kind of stuck in the place and have nowhere else to be, they probably wouldn’t resist looking into it.

If it fits the campaign, you can then simply jump ahead to the next spring and continue from there. There are also a good number of great adventures that can be had during the winter. But these are usually not long expeditions into the wilderness. Much more commonly these are things with isolated villages being threatened and no help coming until spring. The kind of places where you would expect adventurers to stay for the winter. These don’t have to be elaborate adventurers. They can easily be just simple one-shots for a single session, but can also be pretty big things as well. The advantage of this is that you will have the players remember that they actually have experienced a winter and it’s not something that was only mentioned once in passing. For my Ancient Lands campaign, I am planning to make a simple Random Event table, on which I will make one roll for every month in winter camp. With a 1/6 chance four times in a row, something is almost certainly to happen; perhaps even two things. These would probably have to be rolled in advance and not at the table, so you can prepare some material for it. But again, it doesn’t have to be big things. “Frozen Zombies” or “Winter Wolves” would be enough as a hook for the GM. Then you can start with destroyed farms or dead cattle in a stable and have the players deal with it as you usually would in a sandbox. Since the players are kind of stuck in the place and have nowhere else to be, they probably wouldn’t resist looking into it.

But when it comes to running an campaign with a level based system I also got another idea. There’s a small and perhaps not too well known rule in the 1981 Basic Set that characters can never gain enough XP to level up twice after a single adventure. However, the book doesn’t really specificy what constitutes an adventure. I am assuming it means a single session, but when you’re playing the long game you can also think much bigger. Like a whole year bigger. Which, when you consider it narratively, still isn’t really that long. A young adventurer who goes adventuring every year could easily reach 9th level well before age 30. Make it twice as much and you end up with PCs reaching their maximum number of Hit Dice around 40. That seems very appropriate to me.

In fact, it would be quite critical that the campaign is laid out so that characters don’t reach their annual XP cap on a regular basis. The required XP scores for advancing to the next level are roughly doubling with each level which leads to lower level characters catching up to higher level characters pretty quickly. Be they replacement characters for dead ones, new additions to the group, or characters who have suffered energy drain. If all the characters in the party reach the XP cap every year, then the lower level characters will never be able to catch up. So when you estimate how much adventuring the party will be doing in a year, I think aiming for half the XP needed to have the highest level PC reach the next level would be a good baseline.

If the difference in character levels gets really big you run into some problems with encounters anyway, but it’s going to be troublesome here as well. You can easily have characters with an XP cap a hundred times higher than others, which can very likely mean that the lower level PCs would reach their maximum right after the first session of the season, which I guess wouldn’t really feel that fun for the players. One possible option would be to have a year in which the highest level characters don’t go on adventures. However, unlike with spliting the players into two groups and having them adventuring separately for one or two adventures, you can’t really have these adventures simultaneously when you want the lower level characters to catch up with the higher level ones. The players with the higher level characters would have to wait until the other group has finished its adventuring season before they can get back into the action. I think that wouldn’t really be feasible for more than one session or two. Perhaps those players might like to play henchmen or create secondary characters, but I am not sure if they’d be really happy with that either. While I’ve heard that it used to be quite common for players to semi-retire their high level characters and start new ones in paralel, I don’t know if this is something players would still enjoy doing with the expectations they have today.

Early D&D* was an exploration game, not a combat game.

Early D&D* was an exploration game, not a combat game.

If it fits the campaign, you can then simply jump ahead to the next spring and continue from there. There are also a good number of great adventures that can be had during the winter. But these are usually not long expeditions into the wilderness. Much more commonly these are things with isolated villages being threatened and no help coming until spring. The kind of places where you would expect adventurers to stay for the winter. These don’t have to be elaborate adventurers. They can easily be just simple one-shots for a single session, but can also be pretty big things as well. The advantage of this is that you will have the players remember that they actually have experienced a winter and it’s not something that was only mentioned once in passing. For my Ancient Lands campaign, I am planning to make a simple Random Event table, on which I will make one roll for every month in winter camp. With a 1/6 chance four times in a row, something is almost certainly to happen; perhaps even two things. These would probably have to be rolled in advance and not at the table, so you can prepare some material for it. But again, it doesn’t have to be big things. “Frozen Zombies” or “Winter Wolves” would be enough as a hook for the GM. Then you can start with destroyed farms or dead cattle in a stable and have the players deal with it as you usually would in a sandbox. Since the players are kind of stuck in the place and have nowhere else to be, they probably wouldn’t resist looking into it.

If it fits the campaign, you can then simply jump ahead to the next spring and continue from there. There are also a good number of great adventures that can be had during the winter. But these are usually not long expeditions into the wilderness. Much more commonly these are things with isolated villages being threatened and no help coming until spring. The kind of places where you would expect adventurers to stay for the winter. These don’t have to be elaborate adventurers. They can easily be just simple one-shots for a single session, but can also be pretty big things as well. The advantage of this is that you will have the players remember that they actually have experienced a winter and it’s not something that was only mentioned once in passing. For my Ancient Lands campaign, I am planning to make a simple Random Event table, on which I will make one roll for every month in winter camp. With a 1/6 chance four times in a row, something is almost certainly to happen; perhaps even two things. These would probably have to be rolled in advance and not at the table, so you can prepare some material for it. But again, it doesn’t have to be big things. “Frozen Zombies” or “Winter Wolves” would be enough as a hook for the GM. Then you can start with destroyed farms or dead cattle in a stable and have the players deal with it as you usually would in a sandbox. Since the players are kind of stuck in the place and have nowhere else to be, they probably wouldn’t resist looking into it.