Probably the biggest oddity of the Lamentations of the Flame Princess system that makes it stand apart from any other versions of the Basic/Expert rules of D&D is the specialist class. It takes the position of the traditional thief class but attempts to be a lot more than this narrow character archetype. LotFP really only uses the rules of D&D but does not attempt to retain its style. In fact, it very much gets away from that to be a more generic system. (Which is part of what attracts me to it.)

The specialist is an attempt at greater versatility. You can easily make your specialist a thief, but you don’t have to. By focusing on other abilities you can also use the class to represent a range of characters who would not outright be considered combatants. Which I find very interesting as a possible character concept in a 16th or 17th century campaign that is more about being smart than fighting battles.

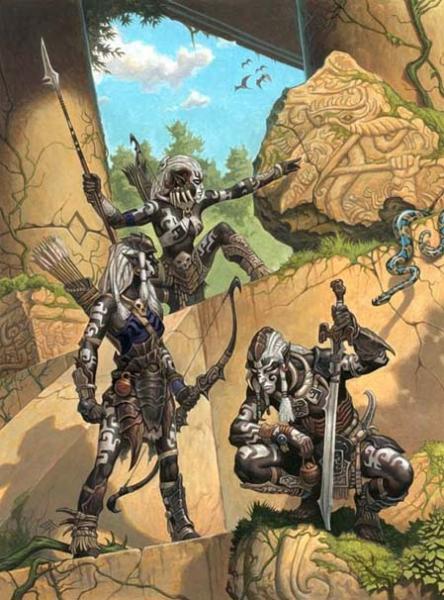

But in a setting like the Old World? This setting is very much Sword & Sorcery with a more hopeful outlook. And Sword & Sorcery is all about… well, swords and sorcery. What’s a noncombatant character to do in such a campaign?

One of the nice things about LotFP is that every character can pick up any weapon and put on any armor and use them. A specialist who is dressed in armor and has a spear or bow in hand fights just as well as any nonheroic warrior. Better actually, with a +1 bonus to attack rolls. And as the character gains more levels, hit points and saving throws keep improving, so even without the bonus to attack that fighters (and scouts) get, you’re still not completely useless in a fight. Quite far from that, actually. As a specialist you won’t be the big ass dragon slayer your fighter friends are, but you’re not limited to stand in a corner and wait until the fight is over. In the LotFP system, clerics, dwarves, nd halflings (which are not classes in the Old World) all fight only just that good as well.

But when does a specialist actually do shine in this setting? When is a specialist better than any other characters in the party? I spend a good amount of time thinking about characters from fiction with dynamics similar to what I have in mind who would make good examples for the specialist class. There weren’t a lot but the two main examples I found are Leia from Star Wars and Naomi Hunter from Metal Gear Solid. And no, it’s not a coincidence: Almost all specialist type characters from pulp-style fiction I could think of are women. That’s how competent female characters in the 30s worked and how it was retained by works that aimed to capture the style. Which is not really a bad thing for a single character. It’s only unfortunate when you end up with all the men as warriors and all the women as clever manipulators. Some sharing between the two is all I want to see. But I think it’s actually a very interesting and fun character archetype.

One thing that almost all these characters have in common is that they are smart and good at talking, which is generally their primary special power. OSR type games usually don’t address that. And I am mostly very much in agreement with that. When you have a group of people together verbally discussing and describing the actions of their characters, then it becomes necessary to rely on abstract game mechanics to represent combat actions, but it makes little sense to do the same thing when their characters are talking. You’re already talking so just say what your character is saying. However, the side effect of this approach is that it really comes down entirely to the players how a conversation with an NPC turns out with the players’ characters making no difference. Having some kind of Persuasion skill for the specialist class would be nice, but it should also be in a way that does not negate the need and purpose of talking with NPCs.

A potential solution to this mismatch of goals is the Angry GM’s advice to not let the players roll any dice when the result won’t make a difference. Say the players talk to a chief and make an offer of alliance which the chief likes. Why roll dice if the players can convince him, he already wants to agree! Or the players make an offer that goes completely against the goals of an NPC. Again,it would be nonsensical to have a player mae a dice roll with a chance of only 2% to succeed. Instead a die roll should be made in situations when the GM just doesn’t know what should happen. Say the players make an offer or demand that the NPC doesn’t really care for but also isn’t fundamentally opposed to. That’s a good situation to call for a roll. For regular characters, the odds to make such a roll is only 1 on a d6, which will mean mostly failures. 1 in 6 is really quite bad so it really makes sense to only have the players roll on these things when you think it probably won’t work but they might get lucky. But specialists have the unique feature of being able to improve the odds of any such skill by one every level and become really good at it.

One benefit of such an approach to specialist skills is that players don’t get to say “I make a Persuasion roll”. In any situation the players first have to talk with the NPCs and at the end the GM decides, based on how the conversation went, whether the NPC has been won over or refuses, or if he wants a player to make a roll for Persuasion.

This is also the same way I approach the Stealth skill. Any character can attempt to be sneaky and for as long as they don’t get close to any guards or stay out of sight this will usually work, no roll required. Sneaking up on a guard in a lit empty corridor while he’s looking in the character’s direction is impossible. But occasionally you might have a player who wants to sneak right up to a guard while there is no loud noises nearby and it would be a minor miracle to pull off. That’s when a role is made. For a fighter with only a 1 in 6 chance this is grasping at straws, but there are many situations where this has to be good enough. But a specialist with a chance of 5 in 6 this might actually be a decent chance to take even without great pressure.

However, I think for my own campaign I am going to remove the option to bring a skill to a chance of 6 in 6, which means that on a 6 a second d6 is rolled and only a second 6 means failure. That’s a chance of failure of only about 3%, which really is too close to being negligible for me. Getting people who are on the fence to come around 80% of the time is already really damn good. You don’t need to be able to impove it to 97%.

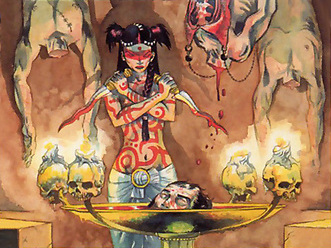

Magic in the Old World is based aroud the idea that the being of any creature is a single entity of spirit and body, but that it extends beyond the boundaries of the physical form that is seen with eyes or felt through touch. The physical forms of creatures and things have clear boundaries, but the immaterial aspects do not. They just weaken with distance and eventually blur together with the essence of everything else. (Similar to gravity or magnetic fields.) Most beings only have mental control over their own bodies and minds, but since everything is connected and the spirit has no clear boundaries, it’s possible to take control over things outside the physical body and even over other beings’ bodies and thoughts through a contest of wills. This control over other creatures or things is magic, as it is used by all witches, shamans, and spirits. One important limitation of magic is that it only works when the caster is actively taking control. When the control ceases, the magic ends. It’s also not possible to use magic against creatures who are not nearby, unless a spirit is send to visit people and use it’s magic on them. It is also the reason why magic objects can not be created; they can only come into existance naturally.

Magic in the Old World is based aroud the idea that the being of any creature is a single entity of spirit and body, but that it extends beyond the boundaries of the physical form that is seen with eyes or felt through touch. The physical forms of creatures and things have clear boundaries, but the immaterial aspects do not. They just weaken with distance and eventually blur together with the essence of everything else. (Similar to gravity or magnetic fields.) Most beings only have mental control over their own bodies and minds, but since everything is connected and the spirit has no clear boundaries, it’s possible to take control over things outside the physical body and even over other beings’ bodies and thoughts through a contest of wills. This control over other creatures or things is magic, as it is used by all witches, shamans, and spirits. One important limitation of magic is that it only works when the caster is actively taking control. When the control ceases, the magic ends. It’s also not possible to use magic against creatures who are not nearby, unless a spirit is send to visit people and use it’s magic on them. It is also the reason why magic objects can not be created; they can only come into existance naturally.