While working on barbarian wilderness settings, I’ve always been swinging back and forth between trying to create a world that is pure wilderness with civilization being something that is only heard but never seen, and city states trying to keep the encroaching Chaos of the wilderness at bay. I have a tendency to just run with whatever has caught my fancy at the moment and losing sight of the bigger picture. I feel that for the last months, I’ve been focusing far too much on the politics and hierarchies of the big cities and drifting away from an actual wilderness setting. But one aspect in particular I found to have neglected the worst is the magical and mystical element of a true primordial wilderness. To that end, I’ve picked up playing some more Dark Souls 3 again, which is just soaked into all that mythic stuff without being an Epic story of great rulers and grand battles. I’ve been inspired by that game even more so than the first back when it came out, but felt that many of my ideas would need much more transformation before they stop seeming like blatant copies of someone else’s popular work. But now I decided screw at all that! I take from Star Wars and Conan without any shame all the time, and it’s only ripping off if you imitate the form without giving it any of your own context. If anyone looks at any of this and thinks, “hey, that reminds me of Dark Souls“, I’m totally fine with it. After all, Dark Souls has Berserk plastered all over it and everyone thinks that’s awesome.

The Three Realms of Kaendor

The world of Kaendor is ancient beyond reckoning. There must have been a point were time first began, but not even the most ancient spirits remember a time before this one. As far as anyone can tell, the world has been the way it is now forever. If there ever was a time before this one, nothing remains to tell of it.

The world of Kaendor is ancient beyond reckoning. There must have been a point were time first began, but not even the most ancient spirits remember a time before this one. As far as anyone can tell, the world has been the way it is now forever. If there ever was a time before this one, nothing remains to tell of it.

The world consists of two primary realms, which the mortals call the Wilds and the Underworld. The Wilds consist of all the forests, mountains, and islands that make up the continent of Kaendor and the unknown lands beyond. They are the world of plants and beasts, and the countless spirits and gods of the Wilds. Beneath the surface of the earth lies the Underworld, the realm of fire and demons. Both realms are primordial and eternal, controlled by supernatural forces and the inscrutable wills of spirits and demons. As the two sides of the natural world, they are neither good nor evil, but they are harsh and uncaring, no more concerned with the fates of mortals than those of beasts. And in the hierarchy of beasts and spirits in the Wilds, mortals stand far below the peak.

But at some point, or perhaps at many different points in the vastness of times, mortals discovered that the power of fire, which occasionally rises into the Wilds from the Underworld by pure chance, can be an incredible weapon and tool to deal with the many threats of the forests and the mountains. By learning to weild and control the fire, mortals gained the ability to change their environments , drive off the beasts that prey on them, and push back against the influence of the spirits that control the weather and the land. And as the power of mortals grew, the small and scattered Civilized Lands they controlled became like a third realm in their own right.

Magic and Civilization

Civilization in Kaendor is not an enduring thing. Once control of the land is gained, it must constantly be maintained to keep the Wilds at bay and keep them from reclaiming what was once theirs. Pacts and truces with the spirits of the surrounding Wilds must be honored and renewed, and the temples and priest-kings must perpetuate the rites to maintain the stability of weather and floods required to grow the food that feeds their cities. But inevitably, there are only two possible fates that await every city and civilization. Even with the powers of temples, the constant unpredictable changes of the Wilds can only be slowed but never stopped, and eventually the prosperity of even the mightiest city will start to fade. As populations decline and roads and fields are no longer maintained, the rites that ensure stability weaken in power until they fail completely. At that point, the Wilds will reclaim the land faster and faster, until their is nothing left but abandoned and overgrown stone walls, which in time will also crumble and disappear.

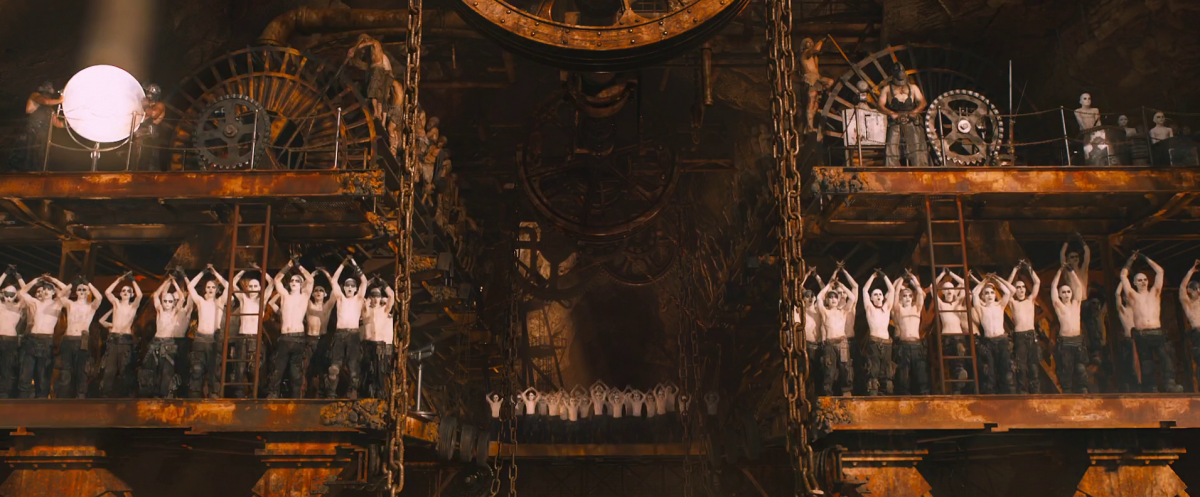

But all too often, people try to escape this inevitable fate, and instead of allowing their civilization to fade, they turn their gaze to the Underworld for powers much greater than simple fire. As ordinary magic draws its powers from the supernatural energies of the Wilds, Sorcery draws on the demonic powers of the Underworld. Not only can sorcery hold back the Wilds even when the power of fire and skills is failing. Sorcerers can create things undreamed of priests, sages, and craftsmen. By using the powers of the Underworld to bend the Wilds to their will, sorcerers believe that they can create civilizations much grander and more prosperous than any that came before them. But there are countless ruined cities overgrown by the forests and crumbling into the sea that stand as proof of their madness. Sorcery may prolong the inevitable end of a declining city, but instead of quietly fading out as the Wilds return, they always end up burning out and leaving nothing but charred cinders. Fire is the main tool of mortals to assert power over the wilds, but if allowed to run free, it will simply consume everything.

The Cult of Heotis

The Fenai of the Dainiva Forest worship three primary deities. Idain, the Lady of the Woods; Livas, the Lord of the Beasts, and Heotis, the Keeper of the Fire. Idain is the goddess of the fields and Livas the god of the herds. Heotis is the goddess of the home. Her role is that of the bringer of fire used for warmth, light, cooking, and smithing, without which mortals would live no different than beasts; but she is also the one who protects the house and the family from its flames. Fire is not good or evil, but it is the demon that is invited into the home, because without it there would be no home. Fire is a blessing, but it also must be respected and feared. Because otherwise it will destroy and kill everything near it.

Wilders

Not all mortals embrace civilization, and there are probably just as many people living simple lives in the forests and mountains, away from the grain fields surrounding the city states. Civilized people call them the Wilders, and look down upon them as savages and heathens. Wilders have found their own way to coexist with the spirits of the Wilds, making pacts with the spirits of the land to live as subjects within their domain and acknowledging their rule through sacrifices. Wilder settlements are small and rely largely on hunting, herding, and foraging, growing no larger than what the domains of the spirits they worship can sustain, and remaining flexible enough to adapt to the changes in their environment.

Not all mortals embrace civilization, and there are probably just as many people living simple lives in the forests and mountains, away from the grain fields surrounding the city states. Civilized people call them the Wilders, and look down upon them as savages and heathens. Wilders have found their own way to coexist with the spirits of the Wilds, making pacts with the spirits of the land to live as subjects within their domain and acknowledging their rule through sacrifices. Wilder settlements are small and rely largely on hunting, herding, and foraging, growing no larger than what the domains of the spirits they worship can sustain, and remaining flexible enough to adapt to the changes in their environment.

Wilders usually use fire only as much as they need for warmth and light, and never to clear land. Though most clans are not above torching the villages of the enemies, which they regard as an additional desecration and humiliation of their foes.

Corruption and the Undead

Eventually, the flames of sorcery will consume the bodies of mortals, but long before that they char their souls. The use and regular exposure to sorcery is not kind on the spirits of mortals. At first it leads to slight madness, but over time leads to the creation of ghouls. Ghouls are still more alive than undead, but as the effects of sorcery continue to gnaw on their flesh, they develop a craving for the flesh of the living to sustain their own failing bodies. Ghouls are not only found among the minions and slaves of sorcerers, but also the desperate inhabitants of old ruins and plains of ash that have been consumed by the flames of the Underworld. Ghouls who practice sorcery eventually rely entirely on the energies of the Underworld to sustain their warped existence and turn into wights, though the same fate can also await their closest servants. If the corruption progresses past this point, eventually the dead flesh with crumble into ash, leaving behind only a spirit of demonic power in the form of a wraith.

Eventually, the flames of sorcery will consume the bodies of mortals, but long before that they char their souls. The use and regular exposure to sorcery is not kind on the spirits of mortals. At first it leads to slight madness, but over time leads to the creation of ghouls. Ghouls are still more alive than undead, but as the effects of sorcery continue to gnaw on their flesh, they develop a craving for the flesh of the living to sustain their own failing bodies. Ghouls are not only found among the minions and slaves of sorcerers, but also the desperate inhabitants of old ruins and plains of ash that have been consumed by the flames of the Underworld. Ghouls who practice sorcery eventually rely entirely on the energies of the Underworld to sustain their warped existence and turn into wights, though the same fate can also await their closest servants. If the corruption progresses past this point, eventually the dead flesh with crumble into ash, leaving behind only a spirit of demonic power in the form of a wraith.

Sometimes people are killed by the powers of sorcery very quickly, completely destroying their bodies and leaving behind only a charred remnant of their soul in the form of a shade.

Skeletons and zombies in Kaendor are always deliberately created by sorcerers or demons and usually have a charred and burned appearance as their dead bodies are animated by faint spirits of flame.