The new Dragonbane game by Free League was released a month ago and yesterday after work I spontaneously got the idea to give it a look, as the pdf is only €23. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect of it, but I am intrigued by what I got.

The new Dragonbane game by Free League was released a month ago and yesterday after work I spontaneously got the idea to give it a look, as the pdf is only €23. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect of it, but I am intrigued by what I got.

Dragonbane is released as a new edition of the old Swedish RPG Drakar och Demoner, which apparently was a pretty big deal with Swedish players back in the 80s. But looking at the rules that we got now, I wonder how much continuity actually is there in the mechanics, because I feel I recognize almost everything from either recent D&D editions or Free League’s Year Zero system. The original game was apparently based on Basic Role Play, which I think is the engine of RuneQuest, but I don’t really have any experience with that.

First of all, this is a very slim game. The main pdf is only 116 pages and the actual rules are all on just 59 pages. I absolutely consider this a rules light system like B/X and Barbarians of Lemuria, though slightly crunchier than the later.

The Core Mechanic and Skills

While it feels quite similar in scope and purpose to B/X, it is a skill based system rather than a class and level based one. As the core mechanic to do pretty much anything, you roll a d20. If the number is lower or equal to your skill rank, you succeed. If it exceeds your skill rank, you fail. Being a guy raised on the d20 system, rolling under instead of rolling over always seems a bit weird, but in this case it really simplifies things in several areas. You don’t have to make any additions or subtractions to the number on the die for every roll and you don’t have to ask the GM for the target number for each specific roll. Your skill is at 14, then just don’t roll over 14.

It also is a neat part of the character advancement mechanic. If you use any skill during an adventure, you mark it on your character sheet. At the end of the adventure, you roll a d20 for every skill that you have used. If that d20 rolls over your current rank, the rank advances by 1. This means that when your skill rank is low, it will go up pretty frequently, but once it is high it will only increase more rarely. This way to you stop being bad at things you do often quickly, but it also can take a long time to actually max out the skill.

Skill checks can also be rolled with either a boon or a bane. Which are really just advantage and disadvantage from D&D 5th ed. Roll two d20 and pick either the better or worse one as your result.

Creating a Character

The first step in creating a character is to roll attributes. These are the same as in D&D and rolled in order with 4d6 keeping the best 3. The attributes determine the starting value for all your skills which will be from 3 for a score of 3, and a 7 for a score of 18. They also determine your Hit Points (equal to Constitution), your Willpower Points (equal to Willpower), and maximum load (equal to half Strength).

The second step is choosing is your character’s kin. The default ones in the game are pretty much the standard generic fantasy peoples plus wolf people and duck people. The character’s kin provides a single special ability that takes Willpower Points to use.

Next is profession. There are 10 professions that each provide the character with another special ability and also have a list from which you have to select six of your trained skills. The skills you select as trained have their starting rank doubled.

Characters’ age works pretty much like in Year Zero: Young character get a +1 to Agility and Constitution but only 2 free additional skills to pick as trained (regardless of profession), while old characters have penalties to attributes but get 6 free additional skills to pick as trained. (Adult characters just get 4 free trained skills.)

Combat

The basic mechanic for combat feel a lot like the d20 and Year Zero systems. Each character gets one action and one movement per round. However, there is no armor class. If you succeed on your melee combat skill check, you hit. If the target of your attack has not yet acted in the current round, it can use its action for the round to immediately make a parry or dodge check to negate the hit. You have to decide to dodge or parry before damage is determined. So I guess the decision depends on how scary the attack looks and how many hit points you still have left. This is the one part of the whole game where I really have no idea how well this actually works out in practice. But characters low on hit points being forced to give up more of their actions to negate hits could actually be a pretty interesting and cool way to represent fighters becoming less effective in combat as they are getting hit. Unlike D&D where you’re at full fighting capacity as long as you still have any hit points remaining. I’m really curious to see this in action.

When a target is getting hit, damage is rolled and then subtracted by its armor rating. This means actual damage might be quite low, which of course lines up with characters only having as many hit points as their Constitution score. A very different approach from D&D where hit points and damage just keep going up forever as characters advance to higher levels and face more powerful opponents. I like that.

When your character is out of hit points, a death roll is made where you need to roll a d20 lower or equal to your Constitution each round. Once you have three successes the character recovers, once you have three failures the character is dead. I believe this is exactly as in D&D 5th ed. There is an optional rule that a character recovering from being dropped has to make one more roll against Constitution and on a failure suffers a severe injury that causes penalties for a couple of days until it heals. This is quite similar to the critical injuries from the Year Zero system, but the severities of the injuries are much lower.

As in old D&D editions like B/X, there are three units of time. Instead of rounds, turns, and days, Dragonbane has rounds, stretches, and shifts which are the same concept, except that there are four shifts in a day. Once per shift, a character can rest for one round to recover 1d6 Willpower Points, or rest for one stretch to recover 1d6 Hit Points. When characters rest for a full shift, they regain all their HP and WP. But don’t remove their severe injuries, which is why I absolutely would use that optional mechanic to have some sense of characters actually getting injured in fights.

This also feels like a good point to mention Conditions. There are six conditions that mirror the six attributes. When a character is suffering from the respective condition, say Exhausted for Strength, then all checks for skills that rely on the respective attribute are rolled with bane, that is roll two d20 and keep the worse one. At a stretch rest, you can remove one of your conditions, and on a shift rest you remove all.

Magic

Unlike the other professions, the Mage does not get a special ability that uses Willpower Points to activate, but instead gets spells. A mage character is trained (double starting rank) in one of three magic skills: Animism is basically druid magic, Elementalism is Fire, Ice, and Stone magic, and Mentalism is telepathy, telekinesis, and divination. All mages can still learn any spells, but their rank in the other two skills starts much lower and they will probably have to deal with a lot of failed castings before they get their ability to useful levels. But at least you make a roll to advance a skill at the end of the adventure as long as you used it just once and it didn’t even have to have been successful.

If the skill check to cast a spell rolls a critical failure on a 20, the caster suffers a magical mishap. As with the severe injuries, these are way less dangerous as the equivalent mechanic in Forbidden Lands. Worst case, a demon is attracted to the caster and will show up during the next shift. What kind of demon and what it wants is left to the GM. No risk of of a dimensional rift opening and tentacles dragging the mage to hell any time you cast a spell.

Limitations of the Core Rules

The package of pdfs that I got is called the Core Rules. I have no idea if there are any other versions of Dragonbane or if there are any planned. But for what is being offered here, the term is very much appropriate. In many ways, this feels like a toolkit of core mechanics more than what most people would typically expect of a complete game. In this version, there are 49 spells and 14 sample monsters, and the five most generic humanoids to pick from (and one non-generic one). Certainly enough for a one-shot or mini campaign in a super generic Middle-Earth fantasy setting, but for anything more fancy than that, you will have to create your own custom content.

And the game seems to be intended to be that way. There are several mentions of more options possibly coming in future releases. There is even an open license that allows anyone to make and publish supplements for Dragonbane, though not to reproduce that content of the core game itself.

There also is really no Gamemaster section in the rulebook worth mentioning. It’s just the mechanics and assumed that anyone playing this game already knows what kinds of campaigns they want to run with it and how to do it.

Which I guess to a certain crowd is just fine. For people already deeply into B/X, OSE, and other games of that category, none of these things might be obstacles. Especially when you are looking for a generic system for which you would have to create the custom creatures of your homebrew setting anyway. And monster and NPC stats are really simple to begin with. Even simpler than in B/X.

I think this might possibly be just the game for me. It’s the purest example I’ve ever seen of what a Fantasy Heartbreaker might look like, with pretty much every single thing it seeming like it was more or less copied over from other games I already known and then welded together. But I really approve of what the designers chose pick for their pieces to turn into this game. From a mechanical perspective, there is not a single thing regarding character creation, advancement, skills, combat, or magic that I don’t like on my first and second read. But if this is all that Dragonbane is going to be, I don’t see it becoming a big breakout hit that will become hugely popular. I can see it getting a reputation similar to Barbarians of Lemuria and maybe with a big dose of luck, get a little time to shine like OSE had some months ago. And I guess that’s fine.

Since I read the whole thing only twice now, I don’t really feel like I could rate it in any way. But being such a light package, I also don’t think there is going to be a lot more learned from a third or fourth reading. I think all that’s left is to just take it for a spin and see how it plays out in practice. It seems like a game that should take very little prep work for adventures when it comes to crunch, so maybe I’ll have an opportunity to give it a try later this summer after I’ve moved closer to my new job and peak work season is over. Certainly looking forward to do it.

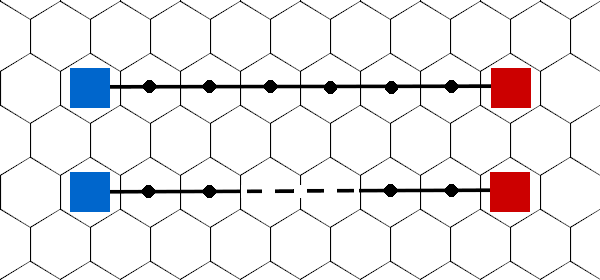

The upper path is an example of regular pointcrawl notation laid over a hexmap grid. Going from the blue site to the read site means going through six hexes between them, costing six time intervals to travel through, and perhaps causing six rolls for random encounters.

The upper path is an example of regular pointcrawl notation laid over a hexmap grid. Going from the blue site to the read site means going through six hexes between them, costing six time intervals to travel through, and perhaps causing six rolls for random encounters.