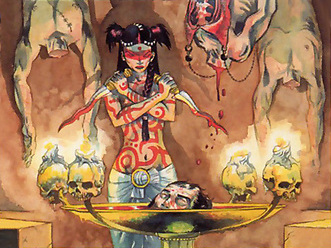

Blood Magic has very much fascinated me since I encountered it in Dragon Age six years or so ago. I wanted to have something like that in my own setting since all the way back when I started planning it. Since then I learned a lot more about how magic works in the Thedas setting and it actually is mostly demonic mind control. Not really much blood involved. But I most liked the idea of blood magic not being fundamentally evil and one of the first blood mages you encounter in the series is actually a pretty nice and also average guy. That had always had me want to have blood magic in my setting and the idea of using blood as a power source instead of some ethereal mana or mental energy is also really cool. It’s much more savage and primitive than arcanists in their libraries playing with astrology. Perfect for a Bronze Age barbarian setting.

But the whole time I never developed the idea further than that, always keeping it off for later. Because I just didn’t have any good idea how blood magic could be different from regular magic and my magic system kept changing all the time anyway. Now I do have a magic system that I really like (but still got not around to write out in full) and with the rest of the setting being already very far along it’s really getting time to finally tackle it.

How it works

Magic in the Old World is based aroud the idea that the being of any creature is a single entity of spirit and body, but that it extends beyond the boundaries of the physical form that is seen with eyes or felt through touch. The physical forms of creatures and things have clear boundaries, but the immaterial aspects do not. They just weaken with distance and eventually blur together with the essence of everything else. (Similar to gravity or magnetic fields.) Most beings only have mental control over their own bodies and minds, but since everything is connected and the spirit has no clear boundaries, it’s possible to take control over things outside the physical body and even over other beings’ bodies and thoughts through a contest of wills. This control over other creatures or things is magic, as it is used by all witches, shamans, and spirits. One important limitation of magic is that it only works when the caster is actively taking control. When the control ceases, the magic ends. It’s also not possible to use magic against creatures who are not nearby, unless a spirit is send to visit people and use it’s magic on them. It is also the reason why magic objects can not be created; they can only come into existance naturally.

Magic in the Old World is based aroud the idea that the being of any creature is a single entity of spirit and body, but that it extends beyond the boundaries of the physical form that is seen with eyes or felt through touch. The physical forms of creatures and things have clear boundaries, but the immaterial aspects do not. They just weaken with distance and eventually blur together with the essence of everything else. (Similar to gravity or magnetic fields.) Most beings only have mental control over their own bodies and minds, but since everything is connected and the spirit has no clear boundaries, it’s possible to take control over things outside the physical body and even over other beings’ bodies and thoughts through a contest of wills. This control over other creatures or things is magic, as it is used by all witches, shamans, and spirits. One important limitation of magic is that it only works when the caster is actively taking control. When the control ceases, the magic ends. It’s also not possible to use magic against creatures who are not nearby, unless a spirit is send to visit people and use it’s magic on them. It is also the reason why magic objects can not be created; they can only come into existance naturally.

Blood magic is one way to get around this limitation. Instead of maintaining control over an enspelled target, a blood mage weaves the spell into the target’s blood, whose life force will then power the magic instead of the mages mental energy. Blood magic keeps working regardless of how far the target moves from the blood mage and the spell can continue potentially for as long as the target lives. Masters of blood magic can even weave spells into the blood of their target that will remain dormant until certain conditions are met and they perform their true enchantment. Having some of its life force consumed by a blood magic spell causes the target to be slightly weakened, depending on the power of the spell. But usually the effect is too small to be a clear sign of blood magic, with the target only being slightly more tired or faster out of breath during strenuous activities.

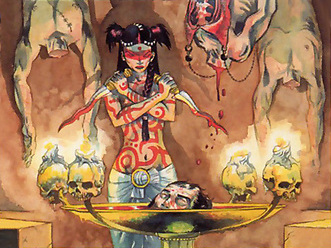

A more well known use of blood in the casting of magic is as an alternative power source to the mental energies of a blood mage. Wrestling control over another person’s body or thoughts is one thing, but actually draining life force from living creatures is much more difficult. Usually this is done by complex rituals and the use of various potions that allow apprentices and acolytes to give their masters access to their mental energies. A simple shortcut to this is to simply tear the blood out of a living creature’s body and use the life force it still carries. This gives a blood mage a great boost to his power when casting a spell. It’s still a difficult thing to do, especially in the middle of a battle, so often blood mages draw on the life energy within their own blood.

Since the corrupted energies that animate undead are very different from the life force of living beings, they are neither affected by it, nor can they use it.

What it does

Aside from giving a blood mage a boost in power from draining life force from a living creature, blood magic can be used to put long lasting enchantments on living creatures. One common use is to make the target creature a permanent slave that has to obey the blood mage’s orders. It’s similar to a powerful charm spell but the ideas planted into the targets mind do not fade away as it remembers its own thoughts and memories.

Alternatively a blood mage can give a creature specific orders to be performed under specific circumstances without it even knowing that such an enchantment is in place. Unlike a spirit following around a victim, such enchantments are very difficult to detect by other witches or shamans. Blood magic can also be used to permanently alter memories. Such enchantments are very difficult to break and require a shaman who knows exactly what he’s looking for. Blood mages familiar with the process can break it just like any other spell.

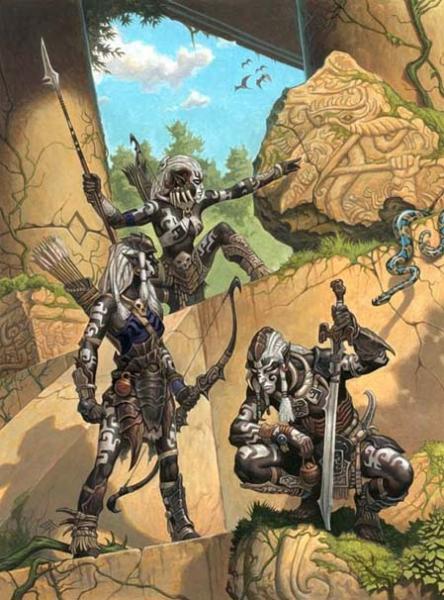

Instead of manipulating a creature’s mind, blood magic can also make changes to the body. Blood mages can give their servants and henchmen great strength and resilience which they retain even without the spell being actively maintained. Since the magic power to maintain these spells is entirely drawn from the creature’s own life force and not the mental energy of the caster, such enchantments tend to take a significant toll on its health. Giving greater strength to heroes for an important battle can often be more than a worthy trade, but guardians who are kept permanently enchanted often live for only a few years. The enchantments keep them strong until the very end but eventually they just fall over dead as desiccated corpses.

How it is treated

Blood magic is not an inherently corrupting or more harmful form of magic but usually seen as one of the darkest forms, similar to sorcery. Tearing the blood of a creature from open wounds is an incredibly violent process compared to the casting of other spells and it’s easy to see why it is especially feared. The effect it has on the bodies and minds of creatures that have been heavily enchanted with blood magic also gives people plenty of reason to regard blood mages as nothing more than savage sorcerers. Blood magic is more common among the more wilder and isolated clans of the Old World and often associated with the witches of the Witchfens, which gives it a reputation of being primitive and brutish though it’s actually a very advanced magical art.

Blood magic also has a much greater potential for manipulating people’s thoughts and controlling their minds than ordinary witchcraft, wich makes known blood mages even much more mistrusted. Even those powerful ancient witches and high shamans who know the secrets of the red art rarely trust their students with such powers and the lack of teachers makes it a very rare skill outside of clans who practice it openly.

RPG implementation

Except for the blood draining ability there are no specific rules for implementing blood magic as a game mechanic. It simply allows blood mages to make their enchantments permanent without any special costs or mechanics.

Magic in the Old World is based aroud the idea that the being of any creature is a single entity of spirit and body, but that it extends beyond the boundaries of the physical form that is seen with eyes or felt through touch. The physical forms of creatures and things have clear boundaries, but the immaterial aspects do not. They just weaken with distance and eventually blur together with the essence of everything else. (Similar to gravity or magnetic fields.) Most beings only have mental control over their own bodies and minds, but since everything is connected and the spirit has no clear boundaries, it’s possible to take control over things outside the physical body and even over other beings’ bodies and thoughts through a contest of wills. This control over other creatures or things is magic, as it is used by all witches, shamans, and spirits. One important limitation of magic is that it only works when the caster is actively taking control. When the control ceases, the magic ends. It’s also not possible to use magic against creatures who are not nearby, unless a spirit is send to visit people and use it’s magic on them. It is also the reason why magic objects can not be created; they can only come into existance naturally.

Magic in the Old World is based aroud the idea that the being of any creature is a single entity of spirit and body, but that it extends beyond the boundaries of the physical form that is seen with eyes or felt through touch. The physical forms of creatures and things have clear boundaries, but the immaterial aspects do not. They just weaken with distance and eventually blur together with the essence of everything else. (Similar to gravity or magnetic fields.) Most beings only have mental control over their own bodies and minds, but since everything is connected and the spirit has no clear boundaries, it’s possible to take control over things outside the physical body and even over other beings’ bodies and thoughts through a contest of wills. This control over other creatures or things is magic, as it is used by all witches, shamans, and spirits. One important limitation of magic is that it only works when the caster is actively taking control. When the control ceases, the magic ends. It’s also not possible to use magic against creatures who are not nearby, unless a spirit is send to visit people and use it’s magic on them. It is also the reason why magic objects can not be created; they can only come into existance naturally.