As I mentioned in my previous post about Encumbrance, supplies of food and water are the main factor of deciding how much weight you can afford to carry, other than treasure. Wilderness adventures have always been the most interesting thing about RPGs for me, and while I think dungeons can be pretty nice when done well, town adventures never were of any real interest to me. Compared to dungeons, the density of threats is much lower in a wilderness even in the most hostile regions. And those dangers you encounter might not be as outright hostile. Compared to towns, a wilderness has very few people you can meet, and its even more rare that those are directly in conflict or allied with each other. When trying to prepare wilderness adventures as a GM, one of the biggest question is what the players might actually do?

Dungeon adventures are players against monsters and town adventures are players against people. Wilderness adventures are players against environment, but since the environment doesn’t have any goals or motives and doesn’t care about what the players do, making adventures in the wilderness needs a somewhat different approach than usual. One way in which the environment can become a big part of the adventures is by including supplies in the campaign.

What can water and rations add to the game?

Food, water, and other supplies all only become important when they have run out. Or when there is a threat they might run out. When this happens, things can get very interesting.

Say, for example, that the players have run out of water. They need to find some and relatively quickly. When they encounter someone who has water, they need to consider their options: Are they trying to just ask for it and hope that those people will share? Are they willing to trade some of their possessions for it? What if those people are hostile? Will the players try to steal water or will they be willing to let themselves be captured to escape looming death? If a fight breaks out they might already be in really bad shape and it would be a fight they absolutely can not afford to lose. Alternatively, the players can steal or destroy the food and water supplies of their enemies and then wait to starve them out to give them an advantage in an upcoming confrontation.

Or instead, the players will have to decide to risk entering a highly dangerous place that might have water. Usually caves and ruins are explored searching for treasure, or the players might consider them too dangerous to be worth the risk. You can always get gold from another place later, but when you’re looking for water there might very well not be a later. There might also be a chance that they could find a safer source of water soon, but they might not be able to reach it if they are getting seriously injured now.

Or you could have another situation in which the players have to get to the other side of an area with very food and water quickly. Should they risk taking the short route straight across, or perhaps take the long route around where they will be able to forage for more supplies. Taking a lot of water on the trip would mean a lot of stuff to carry which might even slow them down enough so that the short route actually takes longer.

There are a lot of interesting things that can happen when supplies are running low.

Making the tracking of supplies practical

But as much as running low on supplies might lead to interesting situations, for as long as as the supplies are lasting nothing is actually happening. Not having supplies is fun. Having them is boring. An in practice, how often will running out of supplies actually happen? Unless you are playing in a desert setting, it’s very unlikely that the players will find themselves in a situation where they begin to starve. My Old World is almost entirely forests, rivers, and coasts, where it probably is going to be particularly rare. Under those circumstances, is it really worth the efford to track the consuming and restocking of supplies every day? To have a nontrivial amount of bookkeeping that then probaly will never actually lead to anything? That really seems like way too much trouble for being worth it.

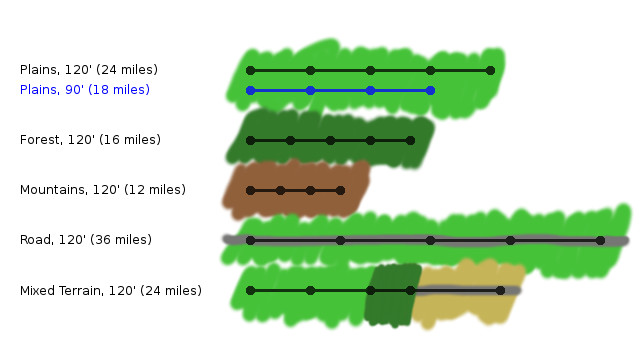

And I had actually already considered to not track supplies at all and with that also ditch Encumbrance as well. But then I got an idea that I think is really clever: One situation in which supplies matter is when travelling light and travelling fast. When you run out of water and food, you will have to make a break in your journey to forrage for it, which could make you lose time that could have been saved if you had packed more from the start. So my idea is this: Normal travel distances per day are based on the assumption that the party is constantly foraging to gather as many new supplies as they consume. But if they have extra rations they don’t need to take time for foraging and can cover additional distance for the day. (Say six additional miles per day, as my Encumbrance system uses 6 miles steps for each category of encumbrance.) This makes ration effectively a consumable item that boost travel speed for a day. If the players don’t use it, it simply is assumed that they always gather some new food while eating the food items that are getting old. So the “ration” items in their inventory remain constantly fresh. As long as the players don’t tell the GM that they are using their rations to increase their travel speed, those rations just quietly sit in the inventory without anyone ever having to think about them. If throughout the whole campaign supplies never become an issue, the rations will just have taken up some inventory space but not caused any amount of bookkeeping work for anyone.

But if it ever happens that the players get in a situation where resupplying might not be possible, this changes. The GM then tells the players that from now on they have to consume rations whether they want to or not. One ration is substracted each day and when they are out, they get whatever effects there are for lack of food and water. (Still have not decided what effects I will use, but I probably make a post when I have picked an option.) If the players decide to go on a journey where this will probably be the case, the GM will tell them as soon as the characters would become aware of it. Which might well be several days before they will actually have to start consuming their rations.

This can also be applied to arrows. In most situations the players will be able to collect a good amount of their arrows and even those that got damage could still be fixed in the field by replacing a shaft with a piece of wood from the forest. Or they might pick up some that have been shot by their opponents. It’s only when the GM thinks that collecting arrows might not be possible that he tells the players to start tracking their arrows now. If the players are fleeing from an enemy and keep shoting arrows behind them, it would be one such situation. If it happens occasionally that players retreat after some arrows have been shot but nobody tracked how many, it’s not going to be a big deal. Just start counting when it becomes clear that running out might become a problem.

This system really is the best of both worlds. It lets me eat my cake and have it too. As long as everything goes fine, supplies completely stay out of everyone’s hair and are fully invisible. But once there is an opportunity to have an adventure with supplies running low, they are instantly there, ready to do their job.