Around the same time that I started reading the Dragonbane rules, road constructions made me take a different route back from work in the evening, leading to me driving through the fields and forests of East Holstein during sunny summer afternoons.

And even though I’m neck deep in setting up a Sword & Sorcery style campaign in Kaendor and frequently tinker around with my Iridium Moons Space Opera, I keep having lots of inspirations for a classic, straightforward Fantasyland setting for Dragonbane. That game very strongly comes across as a good old Fantasy Heartbreaker, but one that actually strikes me as having found a really great balance between oldschool B/X D&D and the Basic Role-Playing system, and incorporating influences from contemporary D&D and the Year Zero system, resulting in just the type of game system that I think I’ve been looking for the last decade. And it’s generic Elfgame style for illustrations is kind of charming. Charming in the same way as I remember first reading the 2nd Edition Forgotten Realms campaign setting box.

And even though I’m neck deep in setting up a Sword & Sorcery style campaign in Kaendor and frequently tinker around with my Iridium Moons Space Opera, I keep having lots of inspirations for a classic, straightforward Fantasyland setting for Dragonbane. That game very strongly comes across as a good old Fantasy Heartbreaker, but one that actually strikes me as having found a really great balance between oldschool B/X D&D and the Basic Role-Playing system, and incorporating influences from contemporary D&D and the Year Zero system, resulting in just the type of game system that I think I’ve been looking for the last decade. And it’s generic Elfgame style for illustrations is kind of charming. Charming in the same way as I remember first reading the 2nd Edition Forgotten Realms campaign setting box.

I’ve been thinking for a long time how I find it disappointing that few fantasy works seem to have any interest to draw on actual medieval history and culture for their settings anymore, and how all Northern European style fantasy is really just Viking stuff and nothing else. And another thing that’s been on my mind last winter was how the Heartlands and Unapproachable East regions of the Forgotten Realms have a couple of interesting ideas, but feel too sparse and thin for me to consider running campaigns in them. But there could be some potential by combining the more interesting parts of both regions into a single region. And then really dialing up the 13th century reference, which the first Forgotten Realms box actually referenced but were then very quickly forgotten and discarded.

And I still think that could work: 13th century Baltic Sea region, with countries shamelessly ripped off from the Dalelands, Moonsea, Impiltur, Rashemen, and Thay. Do I have anything meaningful to add to generic Fantasyland or anything to say on the subject that hasn’t been said before? Not really. I can’t think of any. But there’s still the thought that generic Fantasyland could be done better than it has before, and that I know what it would look like.

Will this go anywhere? Probably not. Will I have interesting pieces to share in the common months? Maybe, but probably not many. Might I actually run a Dragonbane campaign in that setting? Possibly, but I still have a big Kaendor campaign that is in the final preparation phase, which will hopefully go well enough to keep my fantasy cravings fed for the next few years. But maybe, in four or five years, I might find myself in the situation that I feel like running a somewhat different flavor of fantasy. And then, maybe, I might think that this Dragonworld concept I had in 2024 might be worth getting my full attention.

Will this go anywhere? Probably not. Will I have interesting pieces to share in the common months? Maybe, but probably not many. Might I actually run a Dragonbane campaign in that setting? Possibly, but I still have a big Kaendor campaign that is in the final preparation phase, which will hopefully go well enough to keep my fantasy cravings fed for the next few years. But maybe, in four or five years, I might find myself in the situation that I feel like running a somewhat different flavor of fantasy. And then, maybe, I might think that this Dragonworld concept I had in 2024 might be worth getting my full attention.

That’s the kind of worldbuilding work you can expect coming from this.

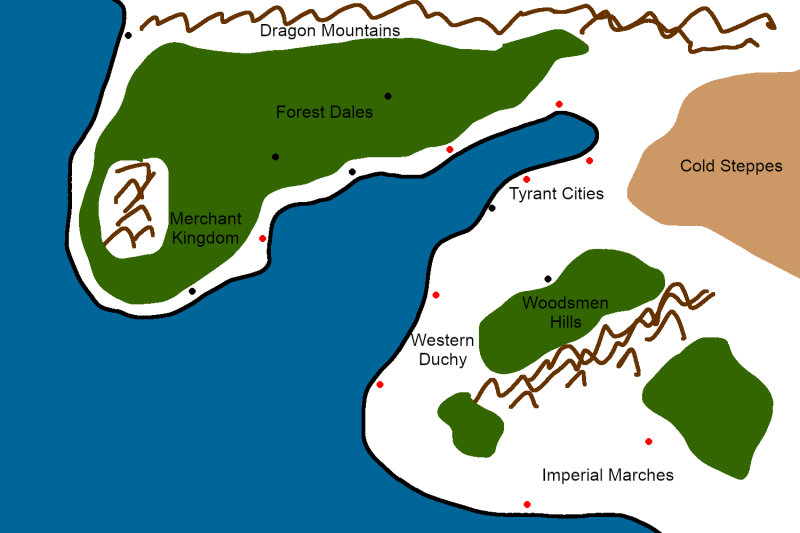

The Lands of Dragonworld

The landscapes and cultures of the setting are very much based on the Baltic Sea region about the time of the 13th century. Temperate to sub-arctic climate and home to various Germanic and Slavic peoples. And the main cultural force that is shaping society throughout all the lands is sea trade. A long an narrow sea protected from the worst weather of the open ocean serves in many ways just like a river for the transportation of goods, but unlike a river there is no way for any powerful lord to block all ships at a strategic choke point and gain control of all trade through huge tolls and taxes. There is even a theory that this open access to a convenient transportation network was the foundation for more egalitarian social structures that eventually made Skandinavia in particular the birthplace of modern Social Democracy, and northern Europe extremely wealthy despite modest to poor conditions for agriculture. (But I digress.) The Baltic Sea became home to many very powerful small merchant republics that ended up playing in the same political and military league as the actual kingdoms of the region. Forgotten Realms also has a very strong presence of free cities and merchant lords, which always reminded me of Northern Europe. I think this is an environment that is really much more interesting than the typical Fantasyland with their English and French kings.

The Imperial Marches are the northern borderlands of a great southern kingdom that fancies itself an Empire but in truth is no more powerful or larger in size than its other neighbors to the south and east. The Empire has long desired to further expand into the lands of the North but has seen almost no successes in the last few generations. The Imperial Marches are home to some of the largest cities in the North and can field large and powerful armies, but most of their excursions into the rest of the region are undertaken by merchant ships trading with the cities of the Narrow Sea.

The Western Duchy is an old and proud nation of herdsmen and farmers sitting on the coastal plains below the Woodsmen Hills. The position of the Duke is a largely ceremonial title as the cities and towns of the country are highly independent, but holds the responsibility of a common leader of the city’s armies in times of attacks by neighboring realms. While the current Duke has sworn fealty to the Emperor as his vassal, in practice the Duchy remains a sovereign nation in nearly all ways that matter.

The Woodmen Hills are a region of densely forested highlands that are inhabited by numerous barbaric tribes closely related to the people of the Western Duchy. While they share very similar languages and worship the same gods, their culture is very different from the plains dwellers down on the coast. Since the Western Duchy has nominally accepted the sovereignty of the Emperor, the Empire has focused its attempts at expansion to the north into the Woodmen Hills, but so far has found very little in the way of success.

The Tyrant Cities are a number of merchant cities with a reputation for lawlessness and the rule of cruel and uncaring despots. They are typically each other’s worst enemies, but also frequently harbor pirates and are busy markets for slaves. Occasionally one tyrant or another attempts to take control over nearby towns in the Western Duchies or Forest Dales, but these conquests are typically short lived as their soldiers are pulled out to defend their cities against rival lords who sensed an opportunity to attack.

The Cold Steppes are the westernmost edge of a vast plain of frozen grasslands that is said to stretch east for thousands of miles. While there are no major settlements in the Steppes, trade caravans from the East occasionally reach the Tyrant Cities or the Western Duchy, and in years of hard winters raids of horse riders from the plains are a common occurrence come spring.

The Forest Dales are a vast region of woodlands on the western shore of the Narrow Sea, though nearly all of the noteworthy towns of the regions are within a few days travel from the coast. There are no significant cities in this part of the northern lands, but it produces much of the special lumbers sought highly by shipbuilders all across the region.

The Merchant Kingdom used to be considered part of the Forest Dales for a very long time until it was settled by merchants from the Empire several centuries before the conquest of the Imperial Marches. Each city is ruled by a council of merchants, and the leaders of each city elect one of their own as their king. A position that is usually assumed for life, but may be revoked by a vote of the grand council. The title of king exists mostly for the merchants to assert their claim to independence from the Empire, which has long desired to incorporate the wealthy and important cities. The merchants of the kingdom gain most of their wealth from trade in lumber from the Forest Dales, iron and copper from the hellish foundries of the Tyrant Cities, and the occasional exotic goods from trade caravans crossing the Cold Steppes, which they sell in ports in the Imperial Marches and lands further south.

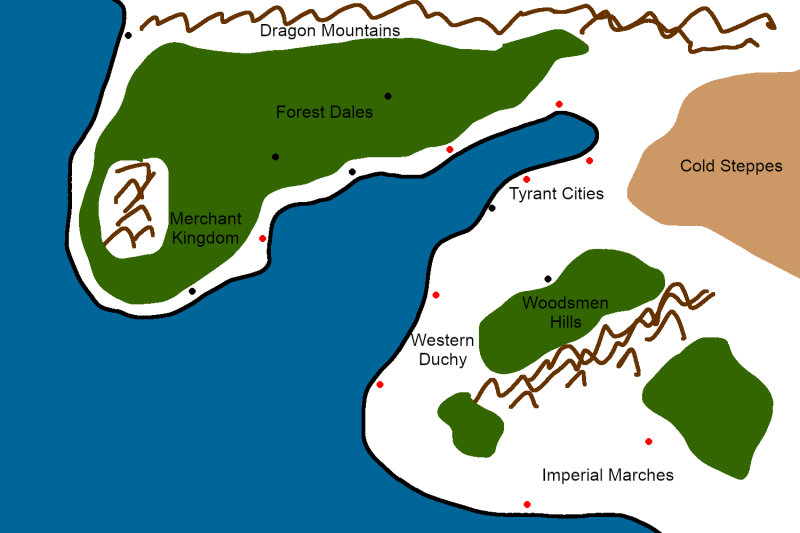

I hadn’t been quite happy with how the first draft of the map for the Forest of High Adventure campaign came out and so I did some big revisions to it that still mostly stuck to the original sketches.

I hadn’t been quite happy with how the first draft of the map for the Forest of High Adventure campaign came out and so I did some big revisions to it that still mostly stuck to the original sketches.