Campaign preparation with ADHD can be challenging. Especially when circumstances keep delaying the start of the campaign and you have plenty of time in which you can’t keep your creativity occupied by building and expanding upon what’s happening in the current adventure. Instead, thinking of alternative ideas that you could use becomes a very inviting creative outlet.

When I started working on my “current campaign” (whatever that might actually mean at this point?), I wanted to make it a Classic Dungeon Crawl West Marches sandbox running Old-School Essentials, because that’s a very simple campaign structure to apply. The PCs go to places holding old treasures, overcome the obstacles in the way, carry out the treasures, and gain XP to become more powerful and able to go into more dangerous and fantastical places to search for even greater treasures. It’s very much a game structure. The mechanics of the game provide the incentive for the players that makes engaging with the obstacles attractive. But three months ago, Dragonbane was released and it turned out to be just the kind of game that I had wish existed before I settled on starting an OSE sandbox campaign. And with not being able to get a campaign launched for still two more months at least, exploring how a potential Dragonbane campaign in Kaendor could be set up is just something that I literally have to do.

Among the many differences between Dragonbane and OSE is that Dragonbane does not have the mechanical incentives that OSE does. Characters advance their skills by using them and may gain an additional Heroic Ability whenever the party has completed a significant goal. This does not in any kind suggest or incentivize any kind of objectives for the players to pursue. When anything you could do is as good as anything else, then nothing is inviting to engage with. And at the start of a new campaign, especially when playing in a new setting, the players don’t really know anything about the world and what kinds of activities are even feasible or will lead to interesting and fun outcomes. When starting a new campaign, the players need to have some kind of guidance which goals and activities will be the most likely to lead them to the most interesting and exciting parts of the setting. In a Classic Dungeon Crawl, that suggested starting point is to look for old ruins and search them for treasures because of how the game mechanics work. In a Dragonbane campaign, and many other games, you have tell the players how they can set out to find the most interesting things in the world that you have prepared.

This reasoning led me to my first question to pursue to hopefully lead me to an answer on how to reach an overall concept for a campaign: “Why is any of this interesting?”

This reasoning led me to my first question to pursue to hopefully lead me to an answer on how to reach an overall concept for a campaign: “Why is any of this interesting?”

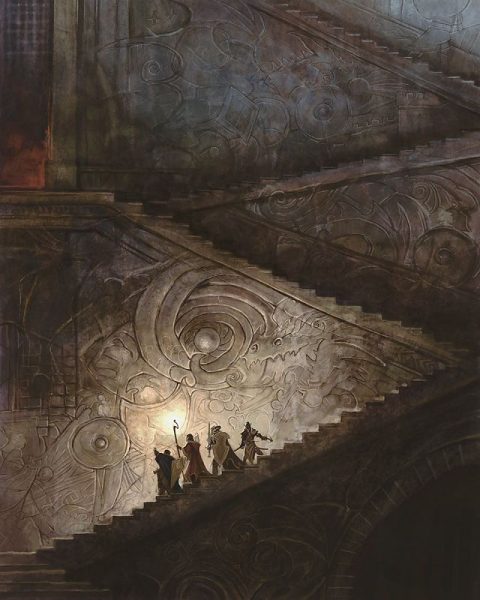

Why would players want to play a campaign in the Kaendor setting? What are the elements of the world that are the most interesting to engage, explore, and interact with? Now I can’t read the minds of players I’ve not even pitched the campaign to yet, but instead I can ask “What are the elements of the Kaendor setting that I find the most interesting?” As these will of course be the elements that get by far the most attention and details during its ongoing creation. The things that I find the most attractive in my concept for the world are the old ruins of the various ancient civilizations, the different typed of spirits and demons that lurk beyond the borders of civilization, the mysteries and possibilities of sorcery, and the numerous secret societies and cults.

Playing RPGs, and what makes them so fascinating and unique as a medium, is all about interacting with things. Questioning and negotiating with other people. Poking at things to see what they do. Opening doors to see what’s behind them. Investigating what the enemies are doing and interfering with it. So after having identified those most interesting elements, a logical next question to ask is: “How can the players interact with these things?”

All these elements have in common that they are things that the people currently inhabiting the world really don’t know that much about. They are mysterious and either inherently supernatural in nature or strongly influenced by it. So the very first thing to do on encountering them is to find out more about them. What is it that players could learn and would want to know about these things:

- What is inside this ruin?

- What was this ruin originally build for?

- What is this unknown creature?

- What is this creature doing here?

- What does this magic item do?

- Where does this magic item come from?

- Who is this secret cult?

- What is this secret cult trying to do?

And looking at this list, a possibly very interesting and compelling campaign concept already suggests itself. This is a world that very much lends itself to provide a lot of interesting material to engage with for characters who are a combination of demon hunters and archeologists. Which really isn’t that different from the typical Classic Dungeon Crawl PCs. They go into ruins to explore, looking for relics of ancient civilizations, and confront the supernatural horrors from the past.

But the incentive structure is rather different. It’s not so much to personally enrich themselves and gain a life of luxury, but because the PCs believe that it is important to learn the secrets hidden in the wilderness and understand the supernatural forces and entities at work in the world. They can be motivated by being worried about possible threats to the mortal peoples, or a deep personal curiosity about the supernatural unknown. Or, if a player wishes so, by the fact that the powerful NPCs who also share these motivations are willing to pay a lot of money to anyone who can bring them such knowledge.

But the incentive structure is rather different. It’s not so much to personally enrich themselves and gain a life of luxury, but because the PCs believe that it is important to learn the secrets hidden in the wilderness and understand the supernatural forces and entities at work in the world. They can be motivated by being worried about possible threats to the mortal peoples, or a deep personal curiosity about the supernatural unknown. Or, if a player wishes so, by the fact that the powerful NPCs who also share these motivations are willing to pay a lot of money to anyone who can bring them such knowledge.

It has always been bothering me a bit that the generic oldschool treasure hunters are only motivated by getting rich, which doesn’t lend itself to interesting social complications. And the typical adventuring heroes who constantly risk their lives to fight evil for strangers out of a sense of compassion or chivalry don’t very much lend themselves to players being proactive and determining goals for themselves. Such characters are kind of compelled to help every possible person in need they encounter, which doesn’t leave them much choices in setting out their own path. But PCs whose guiding motivation is to learn about the unknown and to determine if something might be a possible threat that could cause great damage in the future seems like a nice middle ground between those two extremes. They are characters who you can simply let become aware of a secretive society existing and it’s something that they might want to investigate. You don’t need to have them see the cultist murdering people or stealing a magic artifact to make it clear that they are an evil that needs to be smited immediately.

It’s an interesting approach to what PCs could be and how a campaign could be structures that I am eager to explore further. Any maybe it will be useful to other people to develop a concept and structure for new campaigns by asking “What about this world is the most interesting?” and “How could the players be interacting with it?”