Terry Carr once famously quoted a friend who said “The Golden Age of Science Fiction is twelve.” And when you look at any big list of “Greatest Songs of all time”, you will always find it consisting almost exclusively of songs from the 60s and early 70s. When the generation of today’s music journalists were in their teens. So it really came to absolutely no surprise to me to realize that the really big aesthetic influences on Green Sun all come from around the year 2000, when I was 16.

The seed of the aesthetic that fills my brain was planted by Star Wars, in particular Dagobah, Cloud City, Jabba’s Palace, and Endor. I had first seen the movies in 1994, but my undying love really began in 1997 with the rerelease of the movies and us getting them on video.

The seed of the aesthetic that fills my brain was planted by Star Wars, in particular Dagobah, Cloud City, Jabba’s Palace, and Endor. I had first seen the movies in 1994, but my undying love really began in 1997 with the rerelease of the movies and us getting them on video.

Albion is a neat but rather obscure little German RPG that was released in 1995, but which I only became aware of a couple of years later once I had been hooked by RPGs. It’s a game about a prospecting ship crashing on a planet and discovering that the clouds and strange magnetic field had been hiding a jungle world swarming with life. The two starting characters are rescued by local cat people living in cities consisting of houses made from living trees and I believe there was also supernatural powers involved. From a technical point the game is really ugly and I think it also was even back when it was released, but the design of the world is really quite amazing.

Riven is probably the best remembered adventure game today after The Longest Journey and was released in 1997. The aesthetics of the game are literally out of this world, which I think comes partly from the primitive 3D-pre-rendering technology used to create the environments.

Riven is probably the best remembered adventure game today after The Longest Journey and was released in 1997. The aesthetics of the game are literally out of this world, which I think comes partly from the primitive 3D-pre-rendering technology used to create the environments.

Baldur’s Gate was my gateway to both fantasy and RPGs, but it’s successor Baldur’s Gate II in 2000 surpasses it in every conceivable way. I felt a bit conflicted about the change in visual aesthetics that was quite a move away from the traditional medieval style of the first game. But it is precisely that change to a mediteranean aesthetic with influences from Planescape that stayed with me over the years. I also did play Planescape: Torment around that time and while the game itself never fully won me over, it’s very faithful adaptation of the setting’s visual style and the perfectly matching soundtrack that came with is still nothing but astonishing.

Baldur’s Gate was my gateway to both fantasy and RPGs, but it’s successor Baldur’s Gate II in 2000 surpasses it in every conceivable way. I felt a bit conflicted about the change in visual aesthetics that was quite a move away from the traditional medieval style of the first game. But it is precisely that change to a mediteranean aesthetic with influences from Planescape that stayed with me over the years. I also did play Planescape: Torment around that time and while the game itself never fully won me over, it’s very faithful adaptation of the setting’s visual style and the perfectly matching soundtrack that came with is still nothing but astonishing.

Off all the influences after Star Wars, Morrowind was the big one in 2002. I was captivated by the previews that I had read that I even got the English version before the German version was translated several months later. And I have to say that at this point, my English wasn’t quite up to the task yet. I could kind of manage, but it turned out to always be a strugle. And it certainly didn’t help that Bethesda RPG design still doesn’t click with me to this day. I still don’t understand how you’re meant to play them to get the proper experience. But the world was a whole different story. I was still in the mindset that proper fantasy way was magical rennaisance fair and Morrowind was most certainly not that. Not knowing anything else about the setting, this was more like an alien planet with medieval technology. And I found it to be just pure awesome. Huge mushrooms side by side with trees. Giant insects used for transport, and dinosaurs as farm animals. And of course living god kings represented by their soldiers in bronze armor with bronze masks. I never progressed far into the story and I tried getting back into the game many times, never being able to maintain my interest into playing it for more than a week or two. But every couple of years it’s the strange and alien setting that makes me want to go back.

Off all the influences after Star Wars, Morrowind was the big one in 2002. I was captivated by the previews that I had read that I even got the English version before the German version was translated several months later. And I have to say that at this point, my English wasn’t quite up to the task yet. I could kind of manage, but it turned out to always be a strugle. And it certainly didn’t help that Bethesda RPG design still doesn’t click with me to this day. I still don’t understand how you’re meant to play them to get the proper experience. But the world was a whole different story. I was still in the mindset that proper fantasy way was magical rennaisance fair and Morrowind was most certainly not that. Not knowing anything else about the setting, this was more like an alien planet with medieval technology. And I found it to be just pure awesome. Huge mushrooms side by side with trees. Giant insects used for transport, and dinosaurs as farm animals. And of course living god kings represented by their soldiers in bronze armor with bronze masks. I never progressed far into the story and I tried getting back into the game many times, never being able to maintain my interest into playing it for more than a week or two. But every couple of years it’s the strange and alien setting that makes me want to go back.

Shortly after, in 2003, came Knights of the Old Republic, still widely regarded as the best Star Wars game ever made and in hindsight the clear prototype for Mass Effect (a series that ended up being super-80’s-retro itself). When I played it again recently, I found the game to be quite lacking in many respects, but the style and feel of that game still is as outstanding as it always was. The visual and audio design feels like it is what game creators would have wanted to make a decade earlier if their technology had been up to it.

Shortly after, in 2003, came Knights of the Old Republic, still widely regarded as the best Star Wars game ever made and in hindsight the clear prototype for Mass Effect (a series that ended up being super-80’s-retro itself). When I played it again recently, I found the game to be quite lacking in many respects, but the style and feel of that game still is as outstanding as it always was. The visual and audio design feels like it is what game creators would have wanted to make a decade earlier if their technology had been up to it.

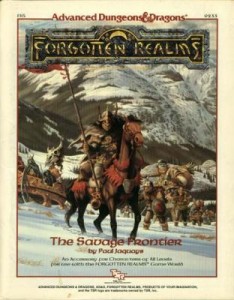

The Savage Frontier is a sourcebook for Dungeons & Dragons that was actually released in 1988, but I think it must have been around 2003 that I first read it. Having played Icewind Dale and Neverwinter Nights, read all the Drizzt books that existed at that time, and becoming involved in the development of an NWN server set on the edge of the High Forest, I hunted down and devoured all material available on the North. And I have to admit that I thought The Savage Frontier was pretty rubbish. To start it all off, it was short. To a teenage German fantasy nerd, detail and minutia are everything. The information was also outdated, and when you have bought in entirely into metaplot and the need for accuracy, old information superceeded by newer sourcebooks is entirely obsolete. It also felt somewhat off. Not sufficently traditionally medieval in style as the 2nd Edition material. But the later, much bigger box of The North has pretty much faded entirely from my mind years ago, while the thin little The Savage Frontier still inspires me again and again.

The Savage Frontier is a sourcebook for Dungeons & Dragons that was actually released in 1988, but I think it must have been around 2003 that I first read it. Having played Icewind Dale and Neverwinter Nights, read all the Drizzt books that existed at that time, and becoming involved in the development of an NWN server set on the edge of the High Forest, I hunted down and devoured all material available on the North. And I have to admit that I thought The Savage Frontier was pretty rubbish. To start it all off, it was short. To a teenage German fantasy nerd, detail and minutia are everything. The information was also outdated, and when you have bought in entirely into metaplot and the need for accuracy, old information superceeded by newer sourcebooks is entirely obsolete. It also felt somewhat off. Not sufficently traditionally medieval in style as the 2nd Edition material. But the later, much bigger box of The North has pretty much faded entirely from my mind years ago, while the thin little The Savage Frontier still inspires me again and again.

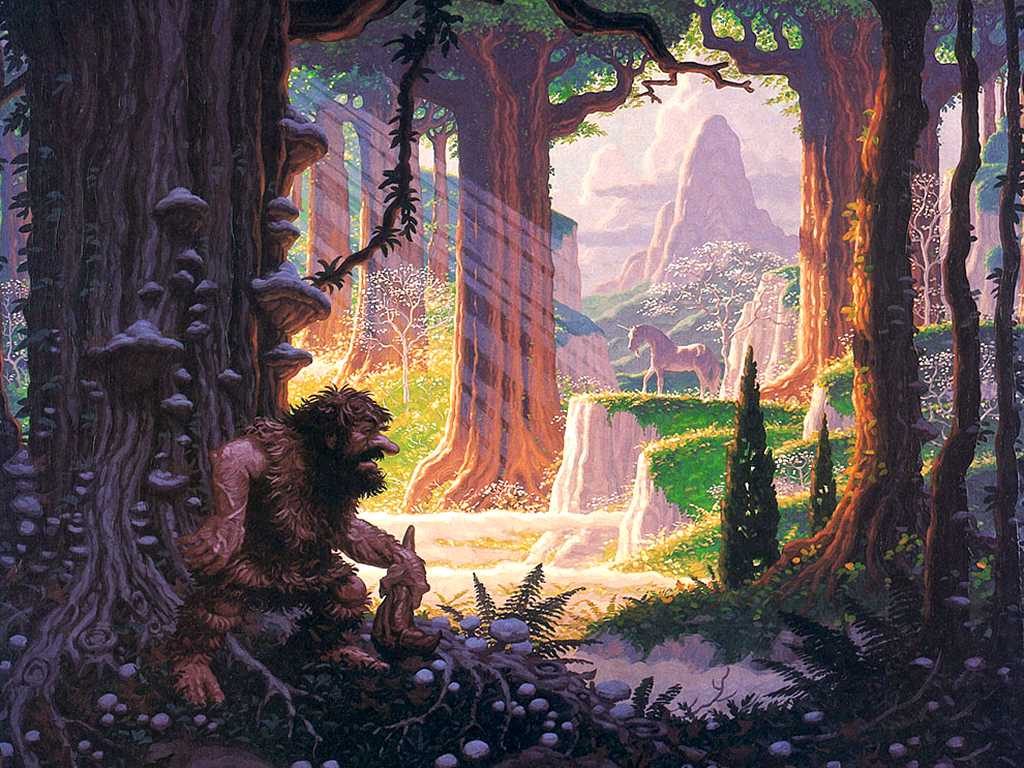

Given how strikingly memorable things in the 80s were, the 90s often feel very much overlooked or even forgotten. But in hindsight, there was a huge sphere of fantasy works that shared a common and actually quite distinct style that was still similar to its precursors from the 70s and 80s, but also evolved into a new form of otherworldly strangeness that at the same time felt weirdly inviting. Like Masters of the Universe, but with a slightly more dreamlike quality. At least to me. I’ve recently become quite a big fan of the wave of Dune games that followed the 1984 movie and tried to evoke it’s aesthetics. I don’t know why, but somehow desert space fantasy settings seem to be one of the biggest influences on my own forest bronze-age fantasy setting.

Given how strikingly memorable things in the 80s were, the 90s often feel very much overlooked or even forgotten. But in hindsight, there was a huge sphere of fantasy works that shared a common and actually quite distinct style that was still similar to its precursors from the 70s and 80s, but also evolved into a new form of otherworldly strangeness that at the same time felt weirdly inviting. Like Masters of the Universe, but with a slightly more dreamlike quality. At least to me. I’ve recently become quite a big fan of the wave of Dune games that followed the 1984 movie and tried to evoke it’s aesthetics. I don’t know why, but somehow desert space fantasy settings seem to be one of the biggest influences on my own forest bronze-age fantasy setting.

But yeah, I don’t really have any actual insights to share. I basically just wanted to gush. This style of fantasy settings is awesome but seems to be getting almost no love. Well, I still love it and I feel no shame in fully embracing it’s slight kitshy undertones.