I’ve been running campaigns for 23 years now, but it’s only been in the last ten or so since I really started to think about roleplaying games and the process of running them conceptually. There’s been a lot of discourse about what games like these actually are and what makes them tick below just the immediate surface level of specific rules since the early 2010s, and following other people’s thought on the subject has taught me a lot of things that are now widely considered to be common mistakes and bad practices. There’s been a lot said and written about how to not run a bad campaign, but to this day I still really don’t have much of a clue how to actually run a great campaign.

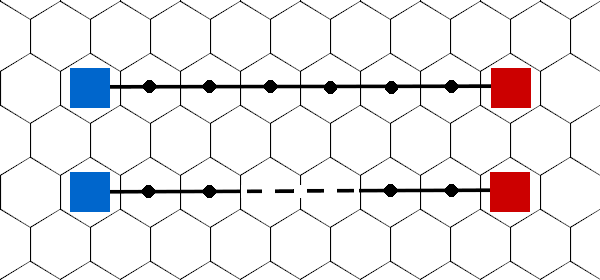

For the last couple of years, my focus as a GM has been primarily on the Classic Dungeon Crawling approach of early D&D in the 70s and early 80s. This is a style of game that is highly structured and procedural as RPGs go, taking place in dungeon corridors and on wilderness hex-maps somewhat reminiscent of board games, with a gameplay that largely revolves around exploring the environment and trying to work out solutions for one obstacle at a time as the players move from one clearly confined area to the next. In a good dungeon or wilderness crawl, things get a bit more complex with useful tools being scattered around the environment that can help with solving the obstacles in complete different areas and multiple possible paths to progress through the environment, but that’s still basically it. It’s a relatively simple form of game in which you mostly just have to create dungeons with good variety of obstacles and then simply follow the procedures spelled out by the rules. It does not require any further thoughts or preparation on dramatic arcs, tension, or narrative pacing. It’s much more of a puzzle game than a narrative thing, and as such relatively foolproof. All the tension and drama is focused on the moment and the scene, but the scenes do not have to come together to constitute a an ongoing, coherent narrative.

However, in recent weeks, I’ve become once more interested in roleplaying games in which the player characters are assuming the role of protagonists in an unfolding story. Which is what I believe is now commonly assumed as the general concept behind the term of roleplaying games and really took off in the mid 80s. Games like these don’t really have the underlying structure of dungeon rooms and wilderness hexes that you can follow through the entire campaign. It’s more about story and story can be anything, and as such there really is no step by step flowchart that you can follow for creating a campaign. And most advice on this subject that I’ve come across over the years I’ve felt to be vague and nebulous and not really helping me in any way. (There’s probably still a lot of things I learned gradually in the form of small bits and pieces, but I don’t remember any big moment of sudden insights or understanding.) I think that there’s actually a fair number of really decent pieces of advice around about things that you really shouldn’t do as a GM because they are counter productive and only cause more problems than they are mistakenly believed to solve. But compared to the many pieces of “do not do those things!”, there seems to be very little around in the way of “do these things!”.

I really am no experienced expert on this subject on running great story-focused campaigns in RPGs. The whole reason I’ve started thinking about this problem is because I want to return to the world of narrative roleplaying games and feel that my old approach from when I started running games is severely underwhelming and I should be able to do way better than that. And in situations like these, when I can’t find any good guides that answer my questions and have to work out something by myself, I always find it really useful to first start by making a list of the things I already do now. This post is me sharing that lists with others and explaining what I mean with the different points.

People always say that there is no wrong way to play roleplaying games, and I guess perhaps there is some truth to that. If something works for people and they are having fun with whatever they are doing, I’m really not going to try telling them to stop and do things the way I think they should be done. But even if there is no wrong way to play, there absolutely is bad advice on how to run games well. And a lot of very widespread and common practices that still get promoted as the default way to run campaigns by the writers of many rulebooks are such bad advice. They are practices that I think nobody should ever adopt, but which just keep hanging around because it’s the way that new gamemasters are still first introduced to running games. The frequency at which you still encounter people in the wild defending railroading and illusionism as actually useful devices to make it easier for GMs to stun their players with amazing scenes is just baffling. When anyone first tells new people about roleplaying games and what makes them such a cool activity, it’s nearly always about how you can play characters who are free to do anything and go anywhere, and how your choices create a unique story as the GM has the NPCs and the world react naturally and logically to whatever you can come up with. This is the promise that RPGs make to players, and I think that we all should expect these from any campaigns we play and don’t accept any campaign that doesn’t. Because what’s the point of all of it then anyway?

The Player Characters are the Protagonists

This should be completely obvious and go without saying. But when you look at any published adventures or campaigns, this is almost never the case. Adventure writers typically want to write out a decent story in advance, and since they pretty much know nothing about who the PCs are going to be and how they would react to things that are going to happen, the stories are simply written to revolve around NPCs instead. Typically villains who do their villain thing and have a tragic backstory, but occasionally an allied NPC who turns out to be a missing princess who needs the help of the PCs to reclaim her kingdom from the villain. And that’s one of the many reasons why almost all published adventures are really bad. Who wants to play in an epic campaign about a great struggle and play henchmen? That’s not what the roleplaying game medium is promising to us! That’s not how people pitch their campaigns! Whatever the story of the campaign turns out to be, it should be the story of the PCs and their deeds. They are the center piece all the events that happen during play are about and they should be the stars of the show.

The Players decide what their Characters do

Again, this is also something that should be completely obvious. But you don’t usually see it in any published adventures, and GMs tend to use those as templates and reference frames when creating their own campaigns. Typically adventures seem to be designed as a sequence of scenes, with the general things that happen in each scene being planned out before the adventure even starts. These scenes are going to happen in a general order of events, though occasionally there will be passages in which a handful of scenes can be played in any order. And in the end it will lead to a final scene in which the PCs face the villain, defeat the villain, and then somehow the villain’s army are no longer a threat. For a structure like this to work, it has to be really obvious what the players need to do in each scene to progress to the next one. Until the players do that specific thing, the story can not continue. And players know that. Typically they have no interest to waste everyone’s time doing stuff that will go nowhere, and so they simply do the very obvious thing that they are supposed to do to continue. Those aren’t choices. That’s not the players making decisions that affect what happens in the story and where the story goes. That’s the players being spectators who roll dice to make the narrator continue with the story. This is not why anyone is excited to get into roleplaying games.

Roleplaying games are completely unique as a medium because they can have stories that develop based on what the players do and decide. Books and movies always have the same stories, and videogames let you pick one of several paths that all have already been written in full. (Sandbox games that have no written story are the notable exception.) Yes, of course you can use roleplaying games as a medium to tell the players a story. But when you got a group of players together and they all learned the rules for a complex game, then why would you choose to do that if instead you could have a game in which the players create a story through their choices? The pre-written adventure completely wastes the unique possibilities of roleplaying games and does not fulfill the promise of the medium. In my view, that makes them inherently inferior and using this format is choosing to play something that is less fun and rewarding than it could be.

The Players decide where their Characters go

This point does overlap with the previous one and is kind of a subset of it. Do not only let the players decide how their characters respond to situations they encounter face to face, but also give them the freedom to choose which of the main areas of the game world they want to investigate further and which of the local conflicts and problems they want to engage with. And also very importantly, give the players full freedom to simply walk away from things when they feel things get too dicey or they have a change of heart about the righteousness of the things they had gotten involved in. Saddling the horses at night and high tailing it out of there to let all the insane idiots fight each other to their own demise could be presented as a proper resolution to an adventure with the PCs taking the moral high ground or saving themselves from a tragic unstoppable doom they were unable to prevent. It does not have to be framed as the players abandoning the adventure halfway through. If the players hear about events elsewhere that interest them, or get caught up in a situation that completely distracts them from what they were originally working at, don’t discourage them and try to get them back on track. At the end of the campaign, the story of the PCs does not have to make for a good novel with clear buildup and resolution and good pacing. When playing an RPG, it’s the tension and drama of the current scene that matters. Let the players chase after whatever has them excited right now. Don’t make them feel obliged to see through everything they started to the end. Cowardly fleeing into the night can be the conclusion to their story. The story they created, with the conclusion they made happen.

The Players choose who they side with or against

Something that had been troubling me for a long time is how you can make any preparations for a campaign so that it will be ready to start playing immediately after the players have made their characters. I’m not a fan of the generic Elfgame Fantasyland in which the players start killing rats and goblins because that’s the kind of things that beginning heroes do out of compassion, and that means it can well take a couple of weeks or a few months to have enough content ready to unleash the players on. And unless you’re thinking ahead to the next campaign with an established group of players while the previous one is still going, you can’t have such a delay between character creation and starting to play. And when you’re recruiting a completely new group of players, you have to have your pitch ready before you can even announce that you’re looking for players. I need to have the campaign played first and then I can start asking who would want to play in it. That means custom tailoring a campaign to the motivations of the party of PCs is not an option.

Then how can you plan ahead what kind of factions you set up in the game world that will be allies and enemies to the players? What if the players think their allies are idiots and they don’t think their enemies are deserving of being stopped and destroyed? The answer is: You don’t. Simply populate the game world with NPCs who are faction leaders, control access to resources, or can provide information and services useful to the players. And then let the players decide who they like or hate, who they trust and who they want to stop. Don’t designate a specific NPC to be the wise guide to the party or the main villain of the campaign. Wait and see which NPCs the players respond to the most and make them appear more frequently and prominently in the future. This way the players will end up with their favorite NPCs as their main allies, and have their most hated NPCs as their main rivals and central villains of their story.

The Players pick which Causes to pick up

Similarly, let the players decide on their own which of the larger issues they encounter in the game world they want to focus their attention and efforts on. There is nothing wrong with having some factions fighting for goals that are clearly noble or evil, but it should also be fun to have several conflicts going on where there could be a story about the players supporting either side. Say you have a charismatic preacher stirring up the peasants to rise up in rebellion against the duke and his soldiers. There could be a story about the PCs joining the peasants to overthrow the monarchy and establish an Anarcho-Syndicalist Commune and dealing with opportunists who plan to subvert the rebellion to make themselves the new lord. Or there could be a story about the PCs coming to the aide of a besieged peaceful duchy that is being threatened to be taken over by an evil priest and his fanatic cultists. Both stories could develop from the same initial setup, depending entirely on how the players perceive and interpret the situation when they first encounter it, and how their first interactions with representative of the factions play out.

Just create a social environment for the game world that has a handful of different factions that have different backgrounds, goals, and methods that puts them at odds with each other. And then let the players decide among themselves which factions they think are deserving of their help and which ones they think need to be stopped. The players need to work out what kind of party they want to play before they make their individual characters, so that their characters have similar ideas about where they stand morally, but that’s a discussion that might take five to ten minutes and is part of the character creation process. If the players think the Necromancer King is super cool and they want to become his undead lieutenants and conquer the great valley of the elves, awesome! If this is a choice that the players make themselves on their own initiative without being prompted that this is what they are supposed to do, it will make all the adventures that follow from it all the more amazing. Worst case scenario the players decide to play goody-two-shoes and decide to ally themselves with the oppressed peasant faction. The players might assume that this is what they were supposed to do, but even then there’s no harm done.

The Player Characters are the Champions of their Cause

Once the players have decided what cause they want to pursue, let their characters be the leading figures who are driving the efforts of the struggle. If they want to see the evil king toppled, led them become the leaders who are uniting the various existing groups of rebels. Don’t relegate them to ordinary soldiers who are getting send on missions that are decided by their higher ups. This goes back to the first point of letting the PCs be the protagonists of the campaign. Let them be the Luke Skywalkers and Princess Leias of the campaign. Let them be the people whose actions and choices will determine the outcome of the struggle. Let them be the heroes.

The Antagonists of the Story are within the Player Characters Means to challenge

However, letting the players be the champions of their cause and heroes of their story does not mean that the PCs have to be the most powerful important people in the game world. They only have to be the most important people in their story. And the story of the campaign could very well be one small part of much larger events that are affecting the greater world. Take for example The Seven Samurai. It’s set in a world of constant civil wars with raiding armies and roaming bandits destroying and plundering all the villages they come across. There is a tale happening somewhere in that world about one warlord rising to the top, defeating and subjugating all the other warlords, and establishing a strong state that cracks down on the bandit problem. But The Seven Samurai is not that story. The heroes of that story do not have fight and defeat all the warlords and their armies to be victorious. They are just seven samurai with no resources and there is no way for them to win the civil war for the control over all of Japan. But that is not their story. Their story is about destroying a gang of some 30 bandits raiding a single unprotected village. This is a threat that the seven samurai are perfectly able to deal with and win against. Great warlords and their armies exist in this world, but they are not the antagonists of the story. When creating adventures for a party of PCs, I think this is something very useful to keep in mind. Look at what kind of opposition the PCs could possible be able to deal with and let them encounter factions (or sub-factions of greater organizations) that are within that scope. Create faction leader NPCs who are of a power level both in game terms and social standing who the players could realistically achieve victory against. They can’t defeat the armies of the great God Emperor and overthrow him, but they might be able to defeat one company of soldiers that occupies a frontier town and slay its commander in battle. If you frame the adventure as a fight against this specific commander and his company of soldiers, instead of focusing on the God Emperor conquering the known world, then defeating them can be an amazing and heroic great victory for the players.

Failure is always an Option

“Well, well, well. If this isn’t the consequences of my own actions.”

When we are dealing with a campaign that does not have a pre-existing script for which scenes are happening in which order and with what outcomes, then any way that a given scene ends up playing out is just as workable as any other. As GM, you are right there at the table as things happen and you have the mental capacity to put yourself in the heads of the NPCs as they are being confronted with events and situations they did never anticipate to happen. No matter how badly things go for the players, nothing will force the story to stop or get caught in a dead end because the story is not written yet. If plans fail spectacularly, battles are lost, cities fall, or major allies get killed, simply roll with it. Yes, in many situations it will feel bad for the players to be faced with failure. But every failure the players experience only reinforces the understanding that every victory and success that follows later was not a given, but the result of their own work. When the players miscalculated and their plans shouldn’t work out, let them fail. When the dice say that a PC or important NPC receives a fatal wound, let them die. This is drama! The players might not be happy about it in the moment it happens, but in the long term, it is these defeats, setbacks, and tragedies that make the campaign memorable and dramatic. Try to be objective and disinterested when making calls on what happens next. Don’t kick their characters down the stairs when you think it would be dramatically appropriate in the situation, and don’t catch them when they slip and fall because it would upset them. Let the players and the randomness of the dice be in charge of the fate of their characters. The game is being played not to tell your story to the players, but to let the players create their own story. If they fail to discover important pieces of information to properly set up their plans, or misinterpret the information that they have, then these failures are on them. Those are mistakes they could have avoided and as a result they have taken risks that they could have seen coming. Let them feel the pain of their own mistakes so that they can truly enjoy the pride of their successes.

False Conclusions are the Fault of the Players

As the GM, you are the connection between the senses of the characters and the minds of the players. The players do not have direct access to what their characters see, hear, or feel, or what common knowledge they have about the world they inhabit. For the players to make reasonable and meaningful decisions, it is absolutely vital that they can have complete trust that the GM is transmitting these pieces of information as accurately as possible with no attempts to manipulate them into false conclusions or foolish actions. The players have no means of any kind to detect or confirm if there’s any kind of trickery or deception going on at this gap between their characters’ minds and their own thoughts. There is nothing clever about tricking players into believing or doing anything by intentionally giving them false or incomplete information at this interface. That’s just plain out lying to your players. And being a dick.

(General GM Advice: It’s always possible that the way you describe something to the players can result in the players getting a different image in their mind than what you’ve been imagining yourself, without any malicious intent involved. This is something that just happens on occasion. The players don’t really have a way to notice a discrepancy between the two mental images. But when you as the GM notice that the players are trying to do something that seems really weird and nonsensical, there is a very good chance that they are making reasonable choices based on wrong information about the current situation. When that is the case, it’s your duty as GM to confirm that everyone is on the same page. It’s your misleading description that caused the situation after all. The easiest way I found to do this is to simply ask the players what they believe their plan or action is going to accomplish. This will usually make any existing misunderstanding very obvious.)

Closing Thoughts

Of course, this is not a comprehensive guide on how to properly set up a campaign for greatness. As I said in the opening of this post, I’m not really sure how to run great open-ended campaigns either and I’m digging into this whole topic precisely because I am trying to discover how. But in my opinion, all these points that I made should make every campaign more interesting and fun compared to not doing them.

I am eager to see how these things will work out for me when I try to apply them in practice.

This reasoning led me to my first question to pursue to hopefully lead me to an answer on how to reach an overall concept for a campaign: “Why is any of this interesting?”

This reasoning led me to my first question to pursue to hopefully lead me to an answer on how to reach an overall concept for a campaign: “Why is any of this interesting?” But the incentive structure is rather different. It’s not so much to personally enrich themselves and gain a life of luxury, but because the PCs believe that it is important to learn the secrets hidden in the wilderness and understand the supernatural forces and entities at work in the world. They can be motivated by being worried about possible threats to the mortal peoples, or a deep personal curiosity about the supernatural unknown. Or, if a player wishes so, by the fact that the powerful NPCs who also share these motivations are willing to pay a lot of money to anyone who can bring them such knowledge.

But the incentive structure is rather different. It’s not so much to personally enrich themselves and gain a life of luxury, but because the PCs believe that it is important to learn the secrets hidden in the wilderness and understand the supernatural forces and entities at work in the world. They can be motivated by being worried about possible threats to the mortal peoples, or a deep personal curiosity about the supernatural unknown. Or, if a player wishes so, by the fact that the powerful NPCs who also share these motivations are willing to pay a lot of money to anyone who can bring them such knowledge.