Among the many different branches of fantasy, one of the more obscure ones that is rarely seen in the wild is Mythic Fantasy. I believe it’s actually more a hypothetical idea than an actual concept anyone is working with in practice. I’ve seen it come up a few times in Fantasy-RPG books for gamemasters, as one of several suggested options for what different forms of styles a fantasy campaign could possibly take. The general idea seems to be fantasy that takes its main inspirations from Iron Age myths of the Greeks, Celts, and Germanic peoples, which tell tales of gods and superhuman heroes. And that’s usually about the full extend of detail for how this kind of fantasy would work. The only concrete suggestions I’ve seen is generally “I don’t know, I guess you use some medusas and minotaurs, or something”. But I say no, that’s not how you make a mythic fantasy campaign. That’s just reenacting Greek myths as an RPG. When we are talking about how we can give a fantasy RPGs like D&D different tones and flavors to make it more similar to other styles of fantastic stories, the goal is to put the default material into a new context. Stories of ancient myth are one thing, but I think when we use the term Mythic Fantasy, we should apply it to something else. Mythic is the adjective that describes that thing. Fantasy is the noun that is the thing.

I’ve been thinking about this these past few days, and I’ve come to a couple of conclusions to how you can create original fantasy material, in a newly envisioned world, and present it in a way that evokes a similar overall feel without just directly copying existing material.

The Monster

This is a big one, and I believe, the most critical of all the points I am going to make here. Modern fantasy in general, and fantasy RPGs in particular, seem to have lost touch with The Monster and forgotten it’s central role it plays in many of the oldest tales that survive to this day. Not all stories need monsters, just as not all fantasy needs to evoke the style of ancient myths. But we just don’t see The Monster anymore. RPGs in particular are full of “monsters”, but these tend to be swarms of critters that appear as the heroes come around the corner, and after a short action scene, are immediately forgotten one’s the turn around the next. Monsters are there to be fought, because fantasy is supposed to have monsters that are fought, but they generally don’t really have any impact on the greater story. The story plays out between human(oid) characters. And I believe this even mostly holds true in D&D, with its big tomes of high level monsters. Yes, you might occasionally have fought a beholder or aboleth. But how often was that creature the main villain of the adventure that the entire story revolved around? What interactions did the PCs have with that big monster before they opened a door and found themselves immediately attacked? These monsters may make big and memorable fights, but from what I’ve seen over the past decades now, they are almost always just window dressing for a story that would work just as well without any monsters in it at all.

This is a big one, and I believe, the most critical of all the points I am going to make here. Modern fantasy in general, and fantasy RPGs in particular, seem to have lost touch with The Monster and forgotten it’s central role it plays in many of the oldest tales that survive to this day. Not all stories need monsters, just as not all fantasy needs to evoke the style of ancient myths. But we just don’t see The Monster anymore. RPGs in particular are full of “monsters”, but these tend to be swarms of critters that appear as the heroes come around the corner, and after a short action scene, are immediately forgotten one’s the turn around the next. Monsters are there to be fought, because fantasy is supposed to have monsters that are fought, but they generally don’t really have any impact on the greater story. The story plays out between human(oid) characters. And I believe this even mostly holds true in D&D, with its big tomes of high level monsters. Yes, you might occasionally have fought a beholder or aboleth. But how often was that creature the main villain of the adventure that the entire story revolved around? What interactions did the PCs have with that big monster before they opened a door and found themselves immediately attacked? These monsters may make big and memorable fights, but from what I’ve seen over the past decades now, they are almost always just window dressing for a story that would work just as well without any monsters in it at all.

This is very much not the case with the monsters of ancient myths. There may be both perception bias by me and survivor bias by the ravages of time, but most if not all of these tales are about one monster. Medusa, the Bull of Minos, the cyclops Polyphemus, Cerberus, Fenris, Grendel, Humbaba, Ravana. They all have a name. They all are known to the people living near them and greatly feared. They have a history. They are not just some random creatures that live by themselves deep in the wilderness, minding their own business. The heroes who fight these monsters are not simply showing of their strength and power, they are performing a great service for the community. Yet somehow, we don’t really see that in modern fantasy. I think having these unique great monsters, that are an active thread to society and that ordinary people can not deal with are a central element of what makes a story feel mythic and really need to be included when trying to make a world that feels like Mythic Fantasy.

The Courts of the High Kings

Mythic tales as a whole seem to have a much bigger focus on specifics than the general, compared to what is overwhelmingly seen in games. Take any setting book for a fantasy RPG and look at the description of cities. If there is any useful information at all, it tends to be general stuff about the overall feel and appearance of the city, for when a group of mercenary adventurers is coming through on their way to new adventures. Cities often are central to mythic stories as well, but usually they are not described at all. When mythic heroes come to a city, they really are coming to a king’s court. That’s really the only part of the city that matters. Perseus comes to Knossos, to meet with King Minos. The city of Knossos is irrelevant to the story. All that is important is the palace of king Minos. Beowulf travels to Heorot, the court of King Hrothgar. We would assume that the king’s hall is inside a small city or town, but it is of no importance of the story. The name of the king’s court is not.

As a broad generalization, mythic tales like to give specific names to all the important characters and places. Myths will often take care to mention the homes and lineages of even secondary characters. It is possible, and perhaps even likely, that the original audiences of these stories would have been able to glean a great amount of context from these pieces of information. The home and lineage of different characters could inform deeper meanings in the things these characters say or the things they do, that are now lost to us. But even so, I still think that we would recognize such thing as being characteristic of ancient myths. And this is something that shouldn’t be too difficult to emulate in a game. When introducing new characters that are to some degree relevant to the story, don’t just tell the players their names and outer appearance, but also have them be introduced as “the son of X, brother to the king of Y”. It does not have to actually mean anything, but it still creates an impression that these things would be greatly meaningful to the people within the world of the story. Present NPCs as important leaders and emissaries, and have other NPCs treat them and speak of them as people who have influence and power, or at very powerful and influential friends. The world of myths is in many ways a very small one, in which everyone knows everyone and everything is connected.

As a broad generalization, mythic tales like to give specific names to all the important characters and places. Myths will often take care to mention the homes and lineages of even secondary characters. It is possible, and perhaps even likely, that the original audiences of these stories would have been able to glean a great amount of context from these pieces of information. The home and lineage of different characters could inform deeper meanings in the things these characters say or the things they do, that are now lost to us. But even so, I still think that we would recognize such thing as being characteristic of ancient myths. And this is something that shouldn’t be too difficult to emulate in a game. When introducing new characters that are to some degree relevant to the story, don’t just tell the players their names and outer appearance, but also have them be introduced as “the son of X, brother to the king of Y”. It does not have to actually mean anything, but it still creates an impression that these things would be greatly meaningful to the people within the world of the story. Present NPCs as important leaders and emissaries, and have other NPCs treat them and speak of them as people who have influence and power, or at very powerful and influential friends. The world of myths is in many ways a very small one, in which everyone knows everyone and everything is connected.

The heroes should be Heroes

In common usage, the term hero is often used to simply mean protagonist. Or simply any person who did something risky out of kindness. But that’s not the original meaning of the term. A mythical hero is a person who stands above all others and exist in a different category than everyone else. And furthermore, they perform great deeds that bring a significant and permanent benefit to society as a whole. Unsurprisingly, many ancient heroes are said to be demigods who are descended from divine beings. A hero almost has to be superhuman by definition. Heroes are the people who go down in history, and they don’t even have to be good guys.

If you want to have a game that feels like stories of myth, the protagonists have to be heroes. And in any kind of roleplaying game, the players have to play the protagonists. There are many awful examples of published adventures where this is not the case and the PCs are merely spectators watching the real heroes do cool stuff and save the day, which has been emulated by countless numbers of GMs. But that’s objectively bad gamemastering and adventure design. The medium of roleplaying games demands that the players play the protagonists of the story. The game is the story of the PCs. In mythic stories the protagonists have to be heroes, and in roleplaying games the PCs have to be the protagonists. This means that in a Mythic Fantasy campaign, the PCs have to be heroes. And what makes or makes not a hero are not their deeds, but the perception of their deeds. A hero is who the people regard as a hero.

If you want to have a game that feels like stories of myth, the protagonists have to be heroes. And in any kind of roleplaying game, the players have to play the protagonists. There are many awful examples of published adventures where this is not the case and the PCs are merely spectators watching the real heroes do cool stuff and save the day, which has been emulated by countless numbers of GMs. But that’s objectively bad gamemastering and adventure design. The medium of roleplaying games demands that the players play the protagonists of the story. The game is the story of the PCs. In mythic stories the protagonists have to be heroes, and in roleplaying games the PCs have to be the protagonists. This means that in a Mythic Fantasy campaign, the PCs have to be heroes. And what makes or makes not a hero are not their deeds, but the perception of their deeds. A hero is who the people regard as a hero.

One major aspect of realizing this in a game is in the way that NPCs talk to the PCs and behave towards them. Heroic PCs should be treated as being exceptional people who stand tall above the common men of women. Heroes mingle among the highest ranking people of society, and they will gain the personal attention of kings and queens when they arrive in a new city, who will treat them with the same honor and respect as foreign dignitaries. Even when the PCs are from simple backgrounds with no titles and few possessions to their name, their deeds elevate them to being part of the elite.

To make this really work and feel believable in an actual campaign, PCs need to exceed the prowess and skills of ordinary warriors pretty early in the campaign. Having PCs start at a higher level or with larger numbers of character points is one option. But I am personally much more in favor of instead having ordinary NPCs all be of the most basic type. The default soldier and brigand are usually good enough for all common soldiers and brigands throughout the entire campaign. When the PCs reach 5th level, there is no need to have them encounter ultra-elite soldiers and brigands. If they can just steamroll over any ordinary warriors they encounter then let them. They are heroes. They are supposed to be superhuman. Equally important is that this makes it more believable that the ordinary soldiers are not capable of dealing with the monsters that threaten their cities and people. In some fantasy setting, many adventure ideas are frequently shot down with the simple reason of “why doesn’t any of the powerful NPCs or the giant armies take care of the problem?”. The answer to that is simple. There are no powerful NPCs. There are no armies that could be wasted to die at the feet of an ancient horror.

Swords of Legend

As with monsters and NPCs, another way to make a game feel more mythic is to apply the same principle of specificity to magic items. In mythic tales, there are no +1 swords or mass produced amulets that are found in some random hole in the ground. Every magic item is unique. Often they have a name, and almost always they have a history. They don’t just lie around to be found by the first person who stumbles upon them. They are either pried from the dead hands of slain main antagonists who used them for their evil purposes, or given as gifts from influential people as rewards for outstanding deeds performed by the heroes. Or alternatively, the heroes go to on a quest to retrieve the items from their ancient resting place, overcoming many hardships and foes along the way.

But even with this in mind, that doesn’t mean that you can’t have any magic items that are discovered unexpectedly in forgotten ruins. A great example of this is early on the movie Conan the Barbarian. Conan has been released from slavery by his master and is being chased by wolves, and trying to climb to safety on top of some rocks, falls into the well hidden entrance of an ancient tomb where he discovers his new sword. Since the movie has barely any dialog, neither the scene nor the sword gets any mention later in the film. But as the story have it, it was supposed to be a highly special and remarkable sword, a relic from the great and powerful realm of Atlantis that has long faded into myth. And in that scene where Conan discovers it in the tomb, this really comes across. He does not just find a sword lying around. He discovers an opulent tomb, with an ancient warrior king in his armor, sitting on a great stone throne, covered in dust and spiderwebs, the sword in his skeletal hand.

We do not know the name of the sword, or the name of the king. And we do not know any of their stories. But the way in which the sword is found makes it clear that this is not just some random sword from the shelf, that you can sell to a village blacksmith in bundles of ten. This is a unique artifact with a great history, even though the tales have been forgotten. And it still might just be a sword +1.

We do not know the name of the sword, or the name of the king. And we do not know any of their stories. But the way in which the sword is found makes it clear that this is not just some random sword from the shelf, that you can sell to a village blacksmith in bundles of ten. This is a unique artifact with a great history, even though the tales have been forgotten. And it still might just be a sword +1.

Illustrations by Justin Sweet, showing scenes from various Kull stories by Robert Howard.

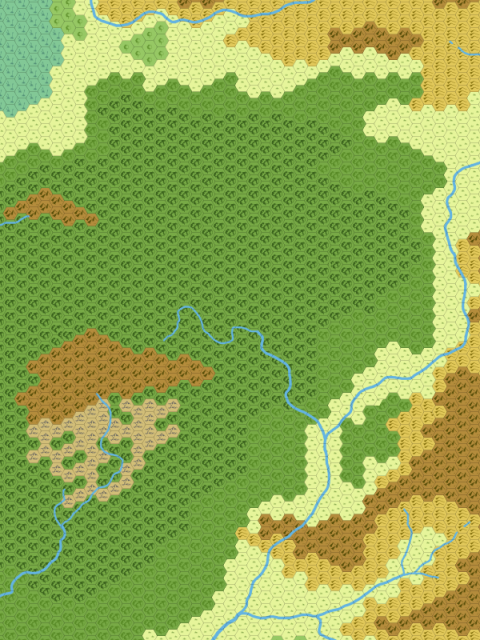

Breaking down the layout for the overall geography like this immediately show the problem. The big weird forest and the naga jungles are in opposite directions? Delving deeper into the wilderness does not bring the party in closer contact with the naga, it takes them further away from them. And it doesn’t make sense for the naga to do some plotting and scheming in old ruins in the great forests because they would first have to get through the cities to get there.

Breaking down the layout for the overall geography like this immediately show the problem. The big weird forest and the naga jungles are in opposite directions? Delving deeper into the wilderness does not bring the party in closer contact with the naga, it takes them further away from them. And it doesn’t make sense for the naga to do some plotting and scheming in old ruins in the great forests because they would first have to get through the cities to get there.