Have you heard the good message of our savior Gus L? I learned entirely by accident that he didn’t stop writing RPG stuff but instead has been sharing new stuff on his new site All Dead Generations for the past three years. All the stuff on the site is about what he calls Classic Dungeon Crawling, which is basically OD&D and early Basic D&D, and how that style of Dungeon Crawling is an exploration fantasy game and not a combat fantasy game. A fantastic resource that I recommend to everyone, though it comes in hefty chunks that take quite a while to chew on.

After my overall pretty great D&D 5th edition campaign last year, I was throwing the towel on trying to make dungeons work, because I just could not figure out how to make a dungeon an interesting place that is not simply a warehouse for nonsensical puzzles. All the advice I was coming across on that front was “Well, sometimes funhouse dungeons can be fun.”But now, after 20 years as a GM, I finally get dungeons!

Dungeon Crawling and exploration in general isn’t just an aspect of an RPG, it’s even more a system of multiple mechanics than I previously had realized. Treating the whole dungeon as one big puzzle that will reveal the safest ways to the best treasures when figured is a great focus draw players engagement with the campaign. Especially when there’s no plot and characters don’t get shiny new toys every time they level up.

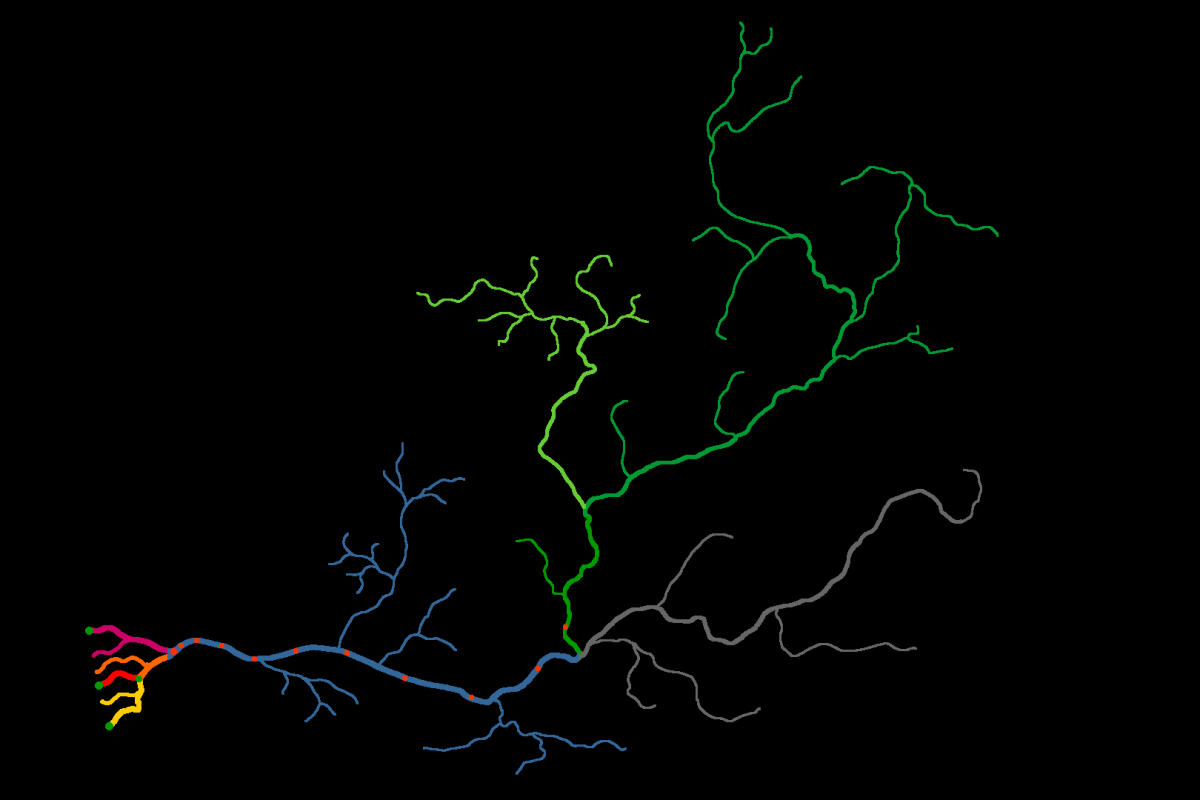

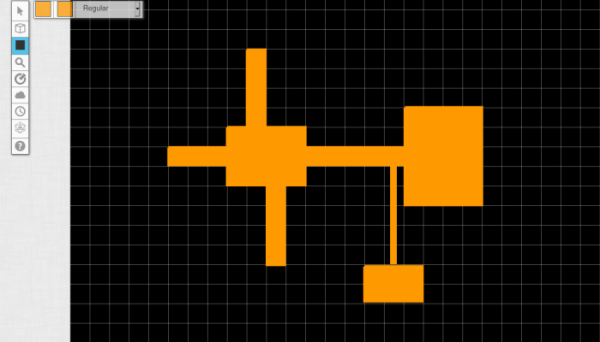

Part of solving that puzzle often is to fully grasp the layout of the dungeon and gain the ability to pinpoint the likely locations of possible shortcuts or otherwise completely inaccessible areas. Gus mentions that having players draw the map themselves is particularly bothersome in online games, where the GM can’t peak at a player’s pencil drawn map to spot obvious misunderstandings of his descriptions. (Minor errors in dimensions are desirable though.) But I took a quick look at Roll20 and found that at least in this case, this thing is actually very easy to do.

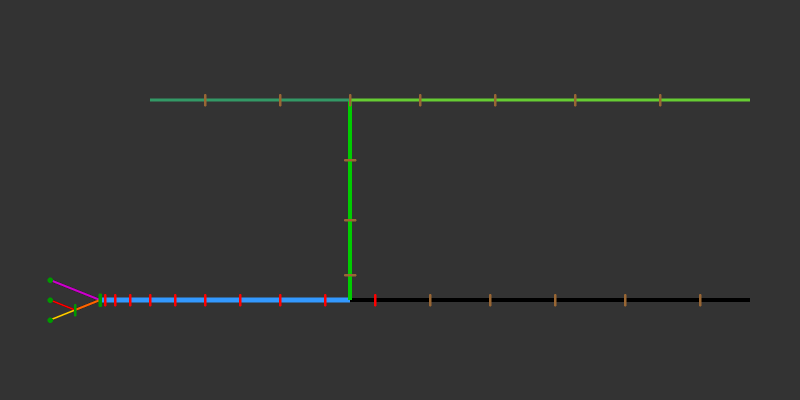

Roll20 has the paintbrush tool, which also has a shapes tool that draws rectangles by simply clicking and dragging. As a lifelong diehard user of pencils and grid paper, I think this is actually a lot easier and quicker than drawing lines around squares with a pencil. To correct errors, you can just click on one of these shapes and delete it, without any messing around with erasers. Now I’m definitely going to bring back this aspect of the game in my Great River Campaign. At least giving it a trial run. I’ve been told that there isn’t a function like this in Fantasy Grounds, but I’ve never used that myself. Which seems like a shame, since this is something really simple and basic. Though I guess when you do your mapping like this, you might not be bothering with something as fancy as Fantasy Grounds.

Roll20 has the paintbrush tool, which also has a shapes tool that draws rectangles by simply clicking and dragging. As a lifelong diehard user of pencils and grid paper, I think this is actually a lot easier and quicker than drawing lines around squares with a pencil. To correct errors, you can just click on one of these shapes and delete it, without any messing around with erasers. Now I’m definitely going to bring back this aspect of the game in my Great River Campaign. At least giving it a trial run. I’ve been told that there isn’t a function like this in Fantasy Grounds, but I’ve never used that myself. Which seems like a shame, since this is something really simple and basic. Though I guess when you do your mapping like this, you might not be bothering with something as fancy as Fantasy Grounds.