We are now resuming our irregular schedule.

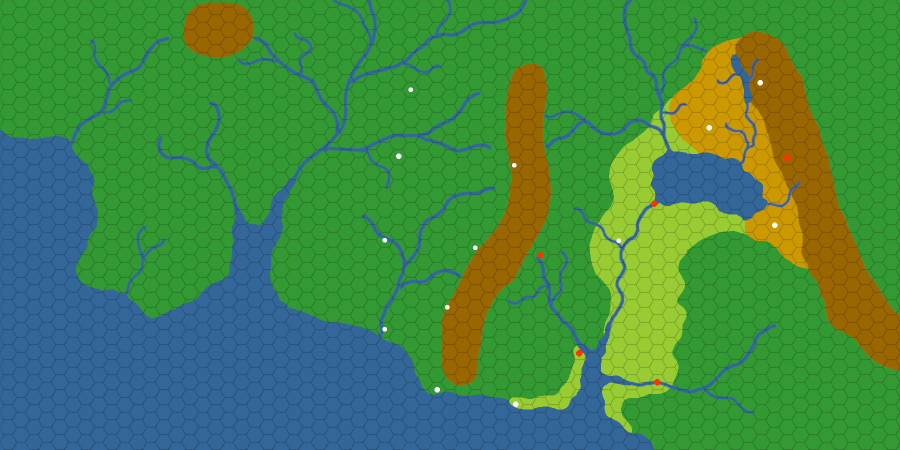

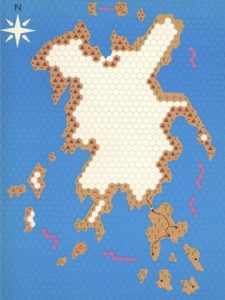

I’ve never been friends with the idea of hexcrawling. Lots of people fill the term with all kinds of different meanings as long as there is at least one hex map involved somewhere, but to me it always carries the clear meaning of being the same concept as dungeoncrawling, translated from dungeon rooms to wilderness hexes. Which means the players are going from hex to hex, color in the new hex on their map as the terrain type they discover, and ask the GM if they see anything that they can check out. Like the player map for The Isle of Dread.

I’ve never been friends with the idea of hexcrawling. Lots of people fill the term with all kinds of different meanings as long as there is at least one hex map involved somewhere, but to me it always carries the clear meaning of being the same concept as dungeoncrawling, translated from dungeon rooms to wilderness hexes. Which means the players are going from hex to hex, color in the new hex on their map as the terrain type they discover, and ask the GM if they see anything that they can check out. Like the player map for The Isle of Dread.

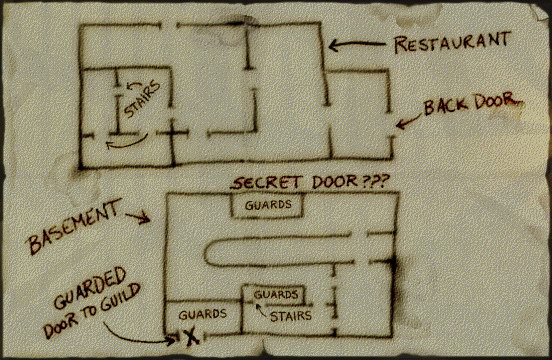

Some people will say that hexcrawling is much more than that, but there’s plenty of people around who strongly assert that every single hex should have something in it to discover, so the idea is there. That just doesn’t sound very fun to me, as it easily turns into wandering around aimlessly waiting for something to happen. I also think it breaks the believability of the world as a 24 square mile area is massive and you could spend month exploring just a single 6-mile hex without ever spotting a cave, statue, or tower that is somewhere between the hills and trees. As I outlined in a previous post, I think it is much more plausible for PCs to find new sites when they either have instructions for how to reach them, or they are visible from a road or river the party is travelling on. In many ways, this is simply a pointcrawl. But there are various things about the pointcrawl map as originally proposed that I find inconvenient for how I want to run my campaigns. Where do you put boxes for new sites that are added to the world as a consequence of players tracking randomly encountered creatures to their lair or base without messing up the map? What if players decide to take shortcuts through woodlands or swamps where there are no roads or rivers to follow? These issues can be quite easily fixed without really overturning the whole system, so consider this a tweak on pointcrawl maps.

Some people will say that hexcrawling is much more than that, but there’s plenty of people around who strongly assert that every single hex should have something in it to discover, so the idea is there. That just doesn’t sound very fun to me, as it easily turns into wandering around aimlessly waiting for something to happen. I also think it breaks the believability of the world as a 24 square mile area is massive and you could spend month exploring just a single 6-mile hex without ever spotting a cave, statue, or tower that is somewhere between the hills and trees. As I outlined in a previous post, I think it is much more plausible for PCs to find new sites when they either have instructions for how to reach them, or they are visible from a road or river the party is travelling on. In many ways, this is simply a pointcrawl. But there are various things about the pointcrawl map as originally proposed that I find inconvenient for how I want to run my campaigns. Where do you put boxes for new sites that are added to the world as a consequence of players tracking randomly encountered creatures to their lair or base without messing up the map? What if players decide to take shortcuts through woodlands or swamps where there are no roads or rivers to follow? These issues can be quite easily fixed without really overturning the whole system, so consider this a tweak on pointcrawl maps.

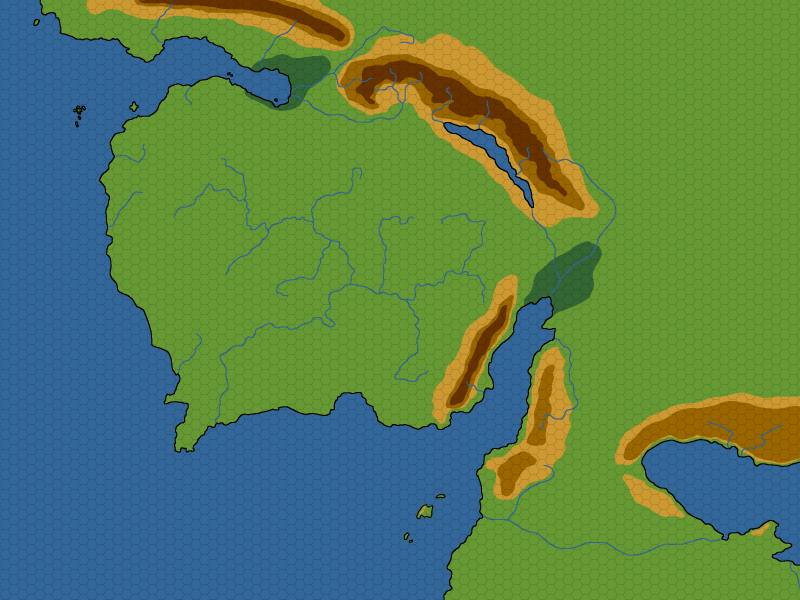

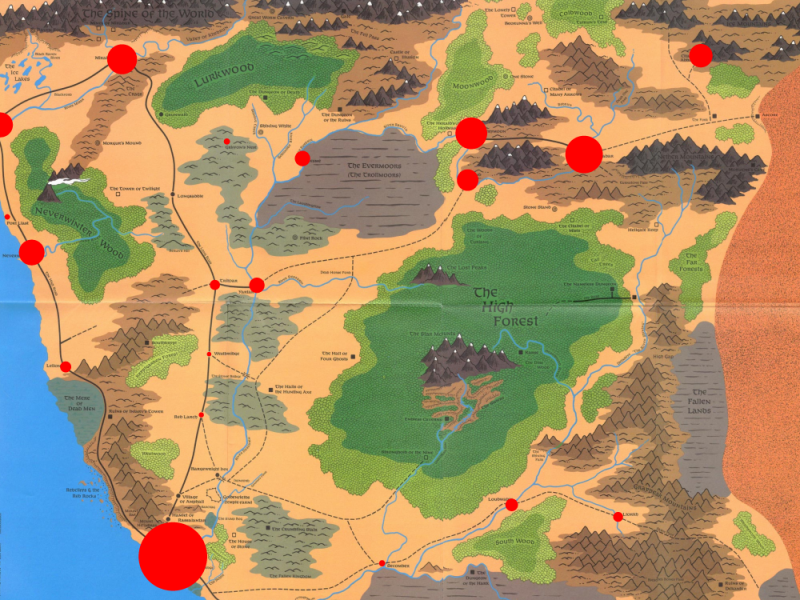

First thing is to draw the map for the area in freehand with no grid. (Even the hexmaps I posted recently started that way before I added the hex grid.) Primarily coastlines, mountains, rivers, lakes, and swamps, and such things.

Second, add the major settlements, strongholds, and ruined cities to the map.

Third, draw the roads that people build to connected these settlements.

Now that we have the main rivers and major roads, as the fourth step, add any other sites that people in the area might have discovered already and could give the players instructions on how to find them.

Fifth, add the secondary paths that connect these sites to the main roads and rivers.

Now we know all the paths through the region that parties are likely to travel on. As the sixth step, add sites that could be spotted by simply traveling on one of the primary and secondary paths.

Seventh, mark paths that connect those tertiary sites to the road and river network. Since characters can see those sites from the road, they don’t need any kind of trail to follow. Just keep it in your sight and move towards it. Depending on the granularity you want with distances, these can even be marked as being right on the trail from which they can be spotted.

Only now comes the step to add a hex grid to the whole map. This hex grid is not to divide the wilderness into segments, but simply as a visual aid to easily estimate the length of swirling paths as they meander through the environment. If you’d want to, you could just note the distances between two points next to the path of the map and remove the grid again if you’re working with a digital map. Back in the day, the 2nd edition Forgotten Realms Campaign Setting box had a hex grid printed on a sheet of clear plastic at the same scale as the maps in the box for just that purpose. I think any print shop would still be able to make such a sheet for you if you have an apprpropriately scaled file of a hex grid on a USB stick.

The advantage of making a wilderness map like this is that I can easily add more dots and more lines to the map, and since the map is based on physical geography instead of a flow-chart abstraction, I can determine the length of any new path easily by counting the number of hexes it passes through. If the players say “You know what, we get off the trail here and just keep heading straight south until we reach the river and then follow it downstream to the town”, it’s trivial to figure out the length of the path, though it would be something you’d have to purely handwave on a default pointcrawl map.

Which might of course be a complete non-issue for many people. This is simply my method that I am using to get the mix of abstraction and precision that I find ideal for my campaigns.