Last week I watched a video by Matt Colville that as a short side note had him mention that from the perspective of a writer, a major part of making the game compelling is “the ability to convey the truths of the world in an easy to grasp manner”. He didn’t go much more into detail than that, but this stuck me as something very close to my unconscious motivations to create a setting like this to begin with. There are of course the aesthetic things. I think huge forests, dinosaurs, giant insects, giant mushrooms, ruined towers, and dramatic weather are cool. But they are not just cool in themselves, they also mean something to me. They are not just elements of a surface picture of the world, but also components of a deeper character and identity of the setting that fuels my inspiration and sense of purpose for all this work. “The truths of the world”is a great phrase to describe it. Maybe you could also call it the internal dynamics or logic of a setting. I think this is where settings really start to shine and become something special. Like Planescape, Dark Sun, Morrowind, and Star Wars. People in these worlds approach the things in their environment in a unique way, and think in concepts and a logic that make sense only in this particular setting. When you get the players to internalize this unique way in which the setting ticks and start to think in its logic without conscious effort, then you succeeded in conveying the truths of the world.

I have written about basic concepts for the serting before, in the very first post. And of course there mostly is an overlap with this post. But those concepts were rather abstract, and don’t answer what they actually mean when it it comes to creating adventures for the setting and running the game with players. “Conveying the truths” was a very useful phrase for me to figure out how to translate it into practice.

The World is huge

Of course, every world is world-sized. For all intents and purposes, all non-multi-dimensional fantasy worlds have the same planet size. But in practice, we never think of a world in planet-scale. Most of western society exists in the modern cities and towns located in the cultivates coastal lowlands. Our native environment consists of landscapes heavily modified or purpose build for humans. The plants around us have been cultivated to grow to sizes that are convenient for the purposes humans intend for them. They only grow in the places and the amounts humans have decided to be the most convenient to them. If you see a very large tree in or near a city, it’s because city planners have decided that a very large tree is perfect for their plans for that spot. We also have no more sense of distance. Flying from Europe to Australia is an 18 hour flight? Wow, that’s long. No! That’s not long! We think of any place in the world as being reachable within a day.

Of course, nature isn’t that way. Nature does not care a single bit what environments would be convenient for human use. Nature is not human-scaled. The world is absolutely massive in scale. This does not mean that the setting needs to have large amounts of content, but for the purposes of player characters, everything in nature is just really inconveniently big. In practice, this means that overland journeys should always be long. On how to make this fun and not a chore, I plan to write some ideas later. But no simple leaving in the morning and being back before sunset. In most cases, I would say getting there should take at least a day, with exploration only starting the next morning at the earlierst.

When it comes to environmental features, everything can be big. Maybe the single biggest influence on the style for this setting is Endor in Return of the Jedi, and those are the biggest trees found anywhere in the world (and quite probably of all time). But that’s just visuals. Tree height has little practical impact. But whenever something would be a serious problem of major inconvenience if it were bigger, that’s a great occasion to make it bigger. When cliffs become really high, gorges really deep, and rivers really wide and strong, they become obstacles that the players have to come up with solutions for to get past. Or monsters could be making their lairs up in trees, but the lowest branches are really high up. Fallen giant trees can be included in ambush sites, serving as 3 meter high walls that affeft the tactics of a fight.

If it were inconvenient if it were bigger, make it bigger.

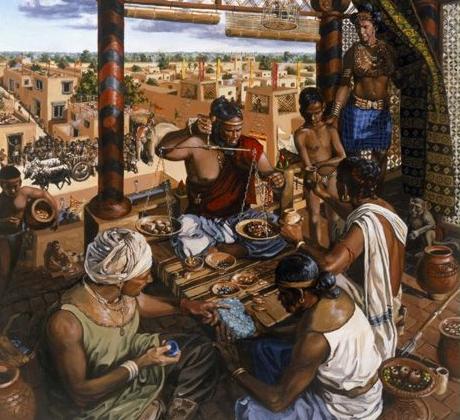

The World is ancient

Very ancient civilizations like the Sumerians and Egyptians are fascinating. 5,000 years ago is an incredibly long time and most people couldn’t even imagine that. It seems like civilizations have been around for practically forever. But what would things have looked like to the ancient Egyptians and Summerians? Their records and historical accounts would go back maybe 400 or 500 years, and then what? Of course there had been people before that for hundreds of thousands of year, but how much would they have known about them? To them, as for us, 99% of humanity’s past would likely have been unknown. But the amount of known history for them would have been much smaller and a much shorter timespan than it is now for us. In a similar way to how we don’t really perceive the size of the world anymore, we are also ignorant of how tiny a fraction the history of human civilization makes up in the full history of the Earth. Unless you are into early Bronze Age cultures like me, you can pick any culture or period from history, and always see how it’s the continuation of something that came before. You can always ask what came before that? My intention with the setting is to make it feel like whatever civilization exists now is just a drop in the vast ocean of time.

One way in which this is already worked into the setting is the lack of a historic timeline. The currently existing cities have an age since their founding, and the most recently ruined cities have have an age since they were destroyed, but those are all mostly in the last 400 years with the founding of the very oldest existing city being 800 years ago. Before that, nothing is known. No stories, no names.

Without a history of the wilderness and the spirits, it’s pretty much impossible to convey their age. But what can be done is to show practically how civilizations come and go, but nature always persists the entire time. While barely anything is known about the most recently destroyed cities, other than stories of how they were destroyed by one of the still existing cities, and nothing about the cities that came before them, there are still plenty of ruins left behind by the Ancient Builders. When showing how much these have been overgrown by the forest, you get some vague implications about the timescales in which the wilderness exists. Imagine a giant ancient palace that has its roof collapsed long ago, and the through the hole get trees growing that are a hundred meters tall and 20 meters in circumference. These giant trees must be ancient, and they only started to grow after the palace had already be turned into rubble. Or you could have the remains of ancient harbors, a hundred miles away from the coast. Occasional signs that there was a large city in a place a long time ago, but there are only the faintest of hints left. Which does come with the implication that there could be even more even older cities pretty much anywhere that have already been completely erradicated by the forest. I also like to put large underground halls under simple unassuming grounds holes in the ground where the ceiling has collapses, burried by several meters of dead leaves that have build up over the centuries. Corral growth on coastal ruins are also fun, showing that the area was at one time beneath the sea and at some point rose above it again. (I’ve seen one such case in Italy, which was the evidence for the discovery of plate tectonics.)

It’s impossible to convey the sense of millions of years of past ages, but showing the short lived nature of current civilizations and how the forest completely erases any of their traces might perhaps evoke some feeling of incredible age.

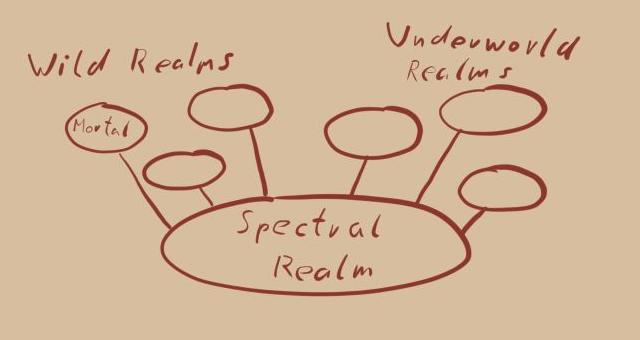

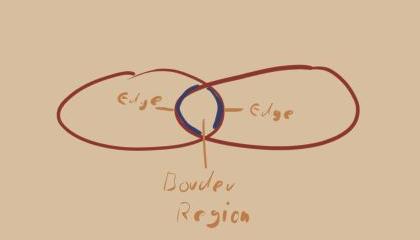

The Material Realm is not the full world

I’ve been somewhat undecided about how the Spiritworld and other planes are supposed to work in this setting, and I am still not fully commited to any specific solution. But thinking about the truths of the world, I believe that this definitely should be one. The world that mortals perceive and interact with is only the surface of true reality. The specific mechanics might still change (probably), but the wilderness through which characters are travelling when they go beyond the borders of settled and explored areas should be full of magical phenomenons that have causes that are invisible to them. When they enter the domains of particularly powerful spirits or descend into the Underworld where the distinction between the natural and the supernatural is no longer as clear as it seems to be in settled areas.

One way in which I think this can be done in practice is to have areas in which the passing of time is inconsistent with what they think of as normal. The length of a day could be considerably longer than 24 hours, or the sun and moons appear to not be moving in the sky at all. Spirits don’t get bored staying in the same place for ages and people could be trapped for decades or centuries without growing hungry, old, or completely insane. Castles could collapse into rubble within minutes, or wildfires burn in place for decades without consuming the trees. And of course, a journey into the wilderness could have you be away for considerably longer than the time you thought you had spend there. (Though in practice I think I want to keep the lost time in months or a small handful of years at the most.)

Spirits are powerful

I am not a fan of the fey from Monster Manuals for several reasons. One thing I realized is that they are pretty much always very weak. This is a world that is not at human-scale, and that also means that its spirits are on a different scale as well. Not much deeper philosophy than this. In practical terms, this means that most spirits that are encountered should be in the mid-range of difficulty, about CR 6 to 12. Alternatively, they appear in groups. I recently revised my naga and shie by downscaling them from their base stats as a yuan-ti from CR7 to CR 5, and a succubus from CR 4 to CR 3. Otherwise, even small groups could slaughter even 6th level groups of above average size.

Another modifications to creatures that serve as spirits is to give them both lair effects and perhaps even regional effects. The bigger spirits are the gods of the land after all.

One of the main ways in which spirits affect the world is in their control of the weather and climate. To show that the spirits are powerful, I want any weather effects to be big. When there are storms, they should be big storms. Not just background flavor, but actually impacting gameplay. And they should be used frequently. The Wilderness exploration system I am working on will have the current weather as one of the random parameters in the rolling of random wilderness encounters.

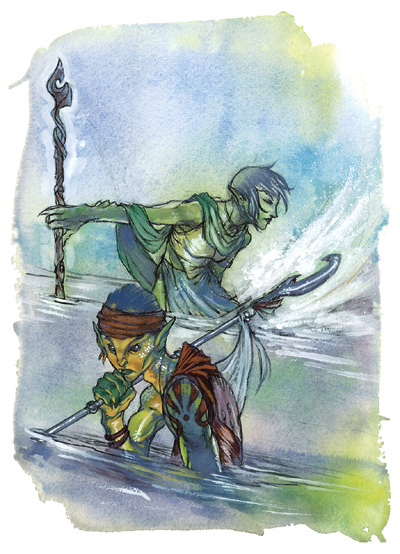

Spirits are alien

The other thing that I don’t like about fey from the Monster Manuals. They are too human. Fey should be dangerous, not just because they have great powers (lots of mortal NPCs do so) but because you don’t know what they might want to do to you. Even when a spirits does not intend to do harm, or feels actively hostile, there is a risk that they could do something that would be harmful for mortals. Even if they intend to help, they might make things worse, and then be unaware that anything is wrong. The concept for the shie is “they look like us, but they are not us”.

Complete random behavior is not desireable, though. To have meaningful interactions with anything, players need to have at least something to work with. My approach to this is to run spirits with “predictable patterns, but unintelligible motives”. Some spirits to certain things. That apparently make perfect sense to them, but not to anyone else. They are incapable of fully explaining themselves to mortals, and in most situations don’t see any need to. They have priorities that stay consistent, even extremely so, but the purpose of those stays completely mysterious. Spirits should never really make full sense, but they must never be random. Before players start to interact with them, their priorities and main behaviors need to be established and fixed into place.

People don’t really matter

This truth is a consequence of several other aspects. The wilderness is huge and ancient, and eventually will swollow up anything that people have made. Spirits are much more powerful and very inflexible in their wishes and as such pretty much always get their will, but what that will is is not only outside of people’s control but also understanding. In the big picture, at the end of the day, all the things that mortals do don’t have any meaningful impact on the world as a whole. Nothing lasts forever. Except for the forest.

The first way in which I approach this is to think that in the hierarchy of creatures, people are the weasels. They are predators who can be very deadly to most smaller creatures and even cause unpleasantness for several larger ones. But against determined bigger beasts, really the only thing they can do is to get out of the way. They don’t rule this world, they are really more at the smaller side of things, their impact not really that visible from a zoomed out perspective. Far from helpless, and far from harmless, but they aren’t anywhere where near the top of the food chain.

In practical terms, this means that players don’t have real hopes to defeat or even stop a god. When a change comes down from the top, the task of the players is to help the population to adapt to the new conditions or escape before it is too late. The only situation in which a coming disaster can be averted is when appeasing the wrath of a god. These things started with people trying to make a change and can only be stopped if the change is reversed and things returned to how they were. When people are the cause of a god’s wrath, then only removing the cause will end the god’s wrath. This builds on the concept of spirits being utterly inflexible in their priorities. It is not possible to prevent the god from using its power, or to change its mind while the cause still exist.

Whatever accoplishments the players might reach can only be important in the here and in the now. They can not fundamentally change anything in the big picture. You can not claim any new land for settling unless it is offered by the local gods. You can not remove a god or make any changes to the environment. You can not remove a type of dangerous creature from its habitat. You could kill a monster that has started to attack farms at the edge of the forest. But you can not clear the valley from which it origially came to make sure none will ever come again.

Adventures should be planned arounf this truth. At the end of the game, the players want to feel that they have accomplished something and have made a difference. When dealing with purely mortal opponents this is not an issue. But when the main threat is supernatural and unstopable, the adventure should be framed in a way that makes it clear that the goal is not to prevent the disaster, but to save the people who will be affected by it.

Overreaching is disastrous

This is part of the ecological subtext of the setting. I’m a trained gardener and was in cultural studies and geography at university, and all of this has given me a perspective on the relationship between people and the environent that “there are no natural disasters”, as one researcher put it. What we percieve as natural and ecological disasters are not random freak accidents of nature, but simple the environment doing what it always does. It’s just that people didn’t look at the patterns in a long enough scale, and build in places where they shouldn’t build, refused to move aside or adjust when a predictable and regular change was coming, and then had no plan what do if anything changes. Or when people made changes to the environment that benefit them in the short term, but didn’t consider that they removed important regulating and moderating from the ecosystem. When you get hit by a massive asteroid, that’s just bad luck, and when you drown in a tsunami that really isn’t your fault. But if you die from disease or starvation after a tsunami or an earthquake, that’s entirely on the people who build build your city. Humans are amazing creatures. In nature there are only a small number of creature that can threaten us and almost none of them want to get anywhere near us if they can avoid it. Pretty much anything else bad that nature can do to us is because people thought they had great ideas to improve the environment and were not aware of the full impact their modifications would have. This really is the underlying philosophy of the entire setting. If you try to make big changes, you get a huge risk. If you want to improve your situation, adjust and try to adapt to the environment. Don’t try to change the environment to suit your wishes.

People don’t really matter in the bigger picture and what threy can accoplish is pretty strictly limited. This doesn’t just apply for the players, but for all NPCs as well. If people try to go beyond these limitations, they will always fail. And the harder they tried, the worse the resulting damage will be. Sometimes the opponents of the players can be villains who want to do evil things. But in this setting, the opponents can just as well be people who have put ambition over caution, setting events into motions that will have disastrous consequences. Not only is there a need to save people from these consequences, the players will also have to get the opponents to give up their ambitions and change their plans. Warlocks are great candidates to play both role, as their art of sorcery is all about getting around the rules of regular magic and the God Kings and Sorcerer Lords of Senkand all work on wrestling control over the environment from the spirits.

Humility will keep you safe

This is the inverse of the previous truth. To survive in the wilderness and deal with the spirits, the key is to aknowledge the limits of your powers and to adapt to the situations you are facing. But I think this approach should apply to all challenges that the players will encounter during adventures. Whenever the players use trickery or make offers of cooperation, this should increase the odds of leading to success. Taking great risks to themselves for the benefit of other should be held in their favor as well.

On the other hand, relying on force and threats, and acting selfish or with pride should not be doing them any favors.

This does not mean that all PCs are required to be humble and kind all the time. But use of force and intimidation will not quickly be forgotten, and the target numbers for success might be a bit higher. Bull headed characters can still succeed. They just are not making things easy for themselves. On the other hand, if such characters do show moments of humility and reserve, this should be held in their favor when deciding on NPC reaction and target numbers.