I recently noticed an issue with my worldbuilding work for Planet Kaendor that I remember having run into several times before over the years. The whole concept is to be a vast world of magical wilderness filled with strange supernatural forces, but a good amount of time I spend working on it actually ends up going on working on the half-dozen major city states, the powerful sorcerer-kings who rule many of them, and the main power groups in the region. None of which is actually supposed to come up much during actual play in an ongoing campaign. I want to have them as part of the setting, but primarily as a form of background flavor that gives a bit more context to what’s happening during play, and help maintaining the appearance of a larger world. You find that applied very well in the Dark Souls games, where you often run into mentions of the far away countries of Astora or Carim, which are given just enough background to make it seem like there’s a story to them, but which never get any actual specific information. You meet a couple of people who say they are from those places, and some item description mention that they are the typical shields of the Knights of Astora or something like that, but that’s really it.

I recently noticed an issue with my worldbuilding work for Planet Kaendor that I remember having run into several times before over the years. The whole concept is to be a vast world of magical wilderness filled with strange supernatural forces, but a good amount of time I spend working on it actually ends up going on working on the half-dozen major city states, the powerful sorcerer-kings who rule many of them, and the main power groups in the region. None of which is actually supposed to come up much during actual play in an ongoing campaign. I want to have them as part of the setting, but primarily as a form of background flavor that gives a bit more context to what’s happening during play, and help maintaining the appearance of a larger world. You find that applied very well in the Dark Souls games, where you often run into mentions of the far away countries of Astora or Carim, which are given just enough background to make it seem like there’s a story to them, but which never get any actual specific information. You meet a couple of people who say they are from those places, and some item description mention that they are the typical shields of the Knights of Astora or something like that, but that’s really it.

I think part of the reason why I keep getting distracted working on places that I don’t actually mean to make any appearances is that most suggested procedures you can find on making a world larger than just a starting village and a dungeon approach the entire process top down. And also assume campaigns dealing with international affairs. First you draw your continent, then you draw the borders between kingdoms, define their governments, identify the influential power groups, and work your way down. An approach that works, but for a setting like Planet Kaendor, it’s already gone completely off target.

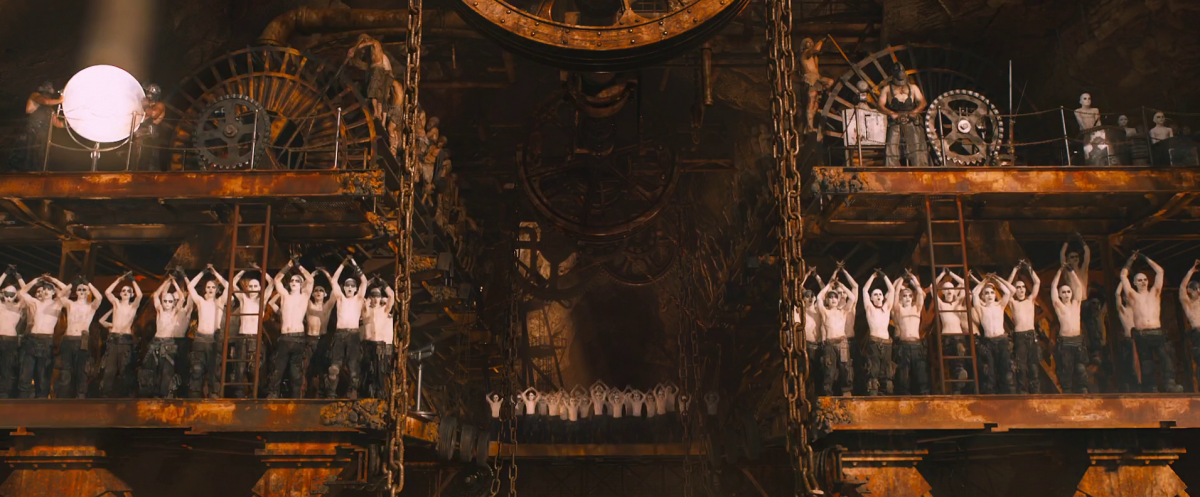

Many, many years ago (almost 10 now, wow) Hill Cantons had a neat little concept of defining different regions as Corelands, Borderlands, and the Weird. And the part that always stood out to me the most is that in the Hill Cantons campaign, the Corelands were considered outside of the play area. They exist, but there’s no adventures there. All adventures happen in the Borderlands, where the fringes of civilization merge with the supernatural, and in the Weird. I think it might be useful, as least for me in my situation, to take this even a bit further. How about actually leaving those city states, which the concept for the cultural level and presence of ruins requires, as blank spots. At least during the primary development of the setting. If their main role is to serve as background detail for some NPCs who are foreigners visiting the places where the actual adventures take place, the city states can be left for last.

In a wilderness campaign, the things that matter the most are what the PCs are actually seeing on the ground, at that moment. When politics and diplomacy become important in such campaigns, it concerns the village they are currently in, and its relationship to one or two neighboring settlements. When you actually look at historic examples, like the Roman wars in Gaul and Germania, you find that those barbarian tribes two thousand years ago were highly organized and very well connected, and everything only makes sense when you account for organized armies from different tribes coordinating their campaigns hundreds of miles away. But here we’re talking about fantasy wilderness, not historical antiquity. And at least in my concept, creating a sense of vastness and desolation, and of a largely unknown and untamed world takes precedent over any kind of realism.

The alternative approach to creating a setting from the top down is to work from the bottom up. You very often find this approach by people recommending to start building just one town and one or two nearby dungeon, and then expanding your map as the players start getting closer to the edges. Absolutely viable approach to having quick and easy adventures, but a side effect of this is that it automatically tends towards creating a very generic Elfgame Fantasyland. When you have to come up with something behind the next hill, you search your memory for what you’ve seen other people do in similar situations, and it’s very easy to end up doing something similar too. It becomes either generic or random, unless you have a bigger picture in mind ahead of time, which defines a different specific style for what fits into the world and what doesn’t.

Which leads to a third option, which is kind of a hybrid of the two, but not simply the middle ground. You start at the top, but instead of working your way down to the bottom step by step, you only do the very most top level stuff to define some basic parameters, and then immediately go all the way to the bottom and work your way up. For example, begin by defining what creatures exist in the setting, how magic works, what levels of technology are available, what religion is like, and how supernatural beings interact with mortals. That’s all at that point. There’s no specific countries, no cities, no rulers, and no major organizations. That’s the kind of stuff that I have developed very highly for Planet Kaendor, and created a style that I find very compelling and well suited for adventures. But it was the cities, rulers, and organizations where I got mired in the mud and found myself unable to create much content that is actually useful in play. Because that’s all stuff that isn’t actually supposed to appear during play.

Here’s my new approach to attempt creating more playable content. For now, I’ll put aside all the notes I have for the city states and their people. Some of that I might bring back, but others could very well end up on the cutting room floor. There’s some really cool ideas I really would want to use, but perhaps Planet Kaendor is just not the place to use them. Instead, my plan is to create one “starting town” for each of the primary environments that I want to be able to visit with a good amount of detail. Instead of continuing to create things abstractly, I try to go specific. Have villages with actual maps, name and describe specific NPCs and their relationships, come up with specific threats to those specific villages. Because at the end of the day, all cool settings in fictions are cool because of the things the main characters see and touch, and the people they talk to, about the things that is directly concerning these people.

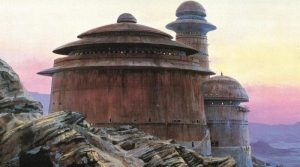

My hope is that at the end, I will have six to ten such villages and small towns that each stand as a showcase and reference point for the entire region they are in. Because in practice and actual play, I mostly will need only one settlement when the players arrive in a new region. That village does not need to have a specific location on a large scale continent map, and could be wherever the party enters the region from. (I think this is where large hex maps had part in sending me down the wrong path.) We also find something very similar in Space Operas. There’s the cliche that planets in science fiction are all homogenous, but that’s highly misleading in most cases. Almost all the time, the protagonists land in only one place and stay within a few kilometers of that landing spot before returning to space. What does the rest of the planet look like? We don’t know. What of all the other planets that the protagonists don’t visit? We don’t know. And it doesn’t matter. In fiction, most of the time, all that matters is within the range of what the protagonists can see. Unless you have a story about international politics, everything beyond that range basically doesn’t exist. And even the Star Wars movies, which are about a galactic political conflict, don’t worry about it one bit. How is the empire actually run? We don’t know, because for the story at hand, it doesn’t matter.