People who’ve been following what I write for some time might know that I often come up with plans for grand ideas but rarely have anything finished to present later. Since I don’t have any money at stake with all this elfgame stuff, that’s fine. And it’s rare that I actually abandon anything I’ve been working on completely. Much of stuff that I create is tinkering with mechanics and concepts and it’s always a learning experience that helps me increase my understanding of the material. And nearly all of it kind of just goes into a drawer where I let it sit for some months or a few years while my attention is on other things, to get pulled out again at some later point to continue tinkering with it. So while it might be pretty early to make any kind of announcement yet for what I am currently working on and nothing might come out of during the next year or so, my current plans for a rules system and campaign setting are actually just a new phase of the same things I’ve been working on for nearly 10 years now. I am constantly getting better at it and feel like I am making great progress, but with increasing experience comes a better understanding of how far away the goal has actually been all along. It’s a bit like fusion power research, I guess.

With a lot of talk, confusion, and general uncertainty about the licensing situation of D&D type games in the last month, plenty of people have come out with the opinion that this is as good a time as there’s ever been to just go through with their ideas of what a perfect game system should look like and make it happen. Though in full self-awareness of how much interest and use such systems might actually see, the old term of fantasy heartbreakers immediately made it back into circulation. It’s not going to be the next Dungeons & Dragons or the next Pathfinder, and most likely not even the next Swords & Wizardry. This is something you do just for the fun of it and maybe to use for your own campaigns, and perhaps, if you’re lucky, it becomes popular enough that some people will take bits and pieces as house rules for their own campaigns. And in this mood and environment, why the hell not? I’ve been collecting quite some house rules myself over the years which I already put together as the Yora Rules, and there’s a number of things in B/X that I would personally have done very differently.

So I’m gonna do this!

So I’m gonna do this!

There are actually three connected but separate things that I want to make:

- A revision of the classes and combat rules of B/X (like attack rolls and saving throws) mostly intended for my own personal use.

- A set of new rules and mechanics for a streamlined wilderness exploration system that makes wilderness travel and resource management simpler and faster, and a system for maintaining a fixed home base to serve as treasure vault, supply depot, and winter camp. I think this one actually has potential to be a successful (free) product.

- A campaign setting for my own next campaign in which I’ll use and playtest the new rules above.

At this stage, these are really more general plans for a playtest than specific plans for a product. These are plans to develop something, which depending on how things work out, could at a later point lead to releasing something.

OSRIC and OSE already set great examples for how you could replicate the structure of AD&D and B/X even with the OGL 1.0a, and with the new Creative Commons license for the SRD 5.1, I feel that all of this is both perfectly within both the letter and spirit of the law.

The Rules Revision

I started RPGs with D&D 3rd edition just when it came out and later played some Pathfinder for a while. It was fine back then because it was what I knew, but when I became curious about this oldschool roleplaying stuff I spend a while with Astonishing Swordsmen & Sorcerers of Hyperborea, as a more accessible way to get into the AD&D mechanic, but since I discovered the Basic/Expert rules eight years ago, I’ve been a huge fan of those rules ever since. That is, at least in general terms. I’ve never been able to actually understand the TSR system for making attack rolls and the saving throw categories seem quite nonsensical for someone who was first introduced to Fortitude, Reflex, and Will. That’s why I always only actually ran Basic Fantasy and Lamentation of the Flame Princess and more recently Old-School Essentials, which all let you make attack rolls like in the d20 system. But I’m also quite a fan of some changes made to the B/X rules by Stars Without Number and its various descendants.

In the big picture, these rules will still be B/X. But with the amount of house rules I already made and some other changes I think would be big improvements to the game, it just seems convenient to do a fully new writeup for everything that I can hand to players and also share publicly. Some of these changes seem quite radical as they throw away a presumed “balance” that Gygax and Moldvay created for different classes. But it’s by now pretty well known that there was no precise fine tuning and diligent play testing for the exact values in the tables, and they just made up numbers that looked right. (If anything does break, it will show up during play tests and can be fixed later.)

- Attack rolls and Armor Class as in d20-system games.

- Saving throws are Physical, Mental, Evasion, and Magic.

- All classes advance at the same XP scores as fighters.

- Attack bonuses and saving throws increase linearly with levels.

- No restrictions on weapons and armor.

- Spellcasting is restricted by encumbrance instead of armor.

- Spells are not lost after casting. (Though still limited in uses per day.)

- Encumbrance based on number of items instead of weights.

- Ability checks are rolled with 2d6 against a target number based on the ability score.

- In dungeons, 1 turn covers exploration of “1 area” instead of a distance of corridor.

- Encumbrance increases the requirement for rest turns instead of reducing exploration speed.

The Wilderness Exploration Game

The Wilderness Exploration Game

While the rules for character advancement, combat, and dungeon exploration in the Basic rules are already pretty nice as a rules light version of D&D, it’s really the Exploration rules that always keep me coming back to this game. I remember when West Marches by Ben Robbins was first making its rounds and it always seemed like a really cool approach to set up a sandbox campaign. I later was greatly inspired by Joseph Manola’s The long haul: time and distance in D&D about approaching adventures as months-long expeditions into the unknown, interrupted by spending months cooped up in winter camp. More recently, I’ve read Gus L’s series on Classic Dungeon Crawls that emphasizes the survival game aspect as being essential to making the exploration of dungeons an engaging mode of play, and the whole time I was thinking “Yes, but what if we apply all of this to the outdoors?!”

I feel the wilderness has always been overshadowed by dungeons and by city adventures, but my own mental images of amazing fantasy worlds are filled with trees and mountains from horizon to horizon. And pondering on the ideas of the three wise men above, I’ve become convinced that there can be absolutely fantastic campaigns in which the wandering around in the wilderness can be the main attraction, rather than just the connecting transition space between different adventure sites. To make such a campaign work, there needs to be a clear campaign structure, as well as a set of easy to use tools for the GM to make it happen.

As campaign structure goes, the concept very much follows the West Marches and the original Basic rules: The game begins with 1st level PCs in a small frontier town that is relatively close to several ruins and caves that are home to various creatures and hiding ancient treasures. At first adventures are relatively short, with the travel to the sites being quick and probably uneventful and dungeons being fairly small, and all the PCs being back in the town after 3 to 5 hours where they get XP for all the treasures they recovered. Dungeons with more dangerous creatures and greater treasures tend to be farther away from the town and descend into greater depth, leading to increasingly longer adventures that eventually won’t be able to be played in a single go.

At this point it becomes strongly encouraged for the players to have more than a single character to deal with scheduling. If players A, B, C, and D go on a longer adventure with characters A(1), B(1), C(1), and D(1), the adventure can’t continue until all four players can come together at the same time with the GM again. If player C can only play every second week (maybe), but players A, B, and D want to play more often, they can go on another adventures with their character A(2), B(2), and D(2), and maybe also take along two other players with their characters E(1) and F(1)? If the campaign is about uncovering the secrets and mysteries of the wilderness instead of the personal stories of individual PCs, this way of playing multiple PCs is perfectly viable and it increased scheduling flexibility immensely. It also makes long healing times and characters working for weeks or months on creating magic items and similar things more viable. Just because one character is out of action for the game doesn’t mean all the other PCs have to sit around and fiddle their thumbs while they are waiting.

The Expert rules recommend that characters should start going on longer journeys deep into the wilderness and away from civilization around 4th level, which I think remains a good guideline. But I also think that this is actually the perfect time for PCs to start establishing their own stronghold. Not as barons ruling over their respective towns and villages (which isn’t really much of a group activity anyway), but to have a new forward base camp for their exploration deeper into the wilderness. It’s a place where they can stash their newly found treasures in their vault (and get XP for said treasures), have a supply depot with food reserves for months, can set up fully stocked shops for armorers and alchemists, and a garrison for the hired mercenaries who guard the vault and stay with the pack animals and supplies while they go down into dungeons to explore. It can also serve as their winter camp when the whether makes campaigning nearly impossible for several months of the year.

This new stronghold not only serves as an alternative for the starting town for launching new adventures deeper into the wilderness, it also functions as a generator for new adventures. Ben Robins recommends that the PCs should be the only adventurers exploring the West Marches, but the players don’t have to be the only people establishing a new outpost on the very edges of civilization. There can also be the keeps of aspiring new barons, mining camps, bandit camps, and of course endless hidden lairs of evil cults. Not to mention monsters like giants and dragons making their homes in the area. All of which could have a problem with the PCs setting up a new base near their own turf. Or potentially become allies to share resources and information, and aid each other in times of attacks.

The critical importance of random encounter in dungeon explorations is well enough known, but the same mechanic can also do an incredible amount of heavy lifting when it comes to the wilderness. Nearly everything that can be encountered in the wilds or on the road is either going somewhere or coming from somewhere. After the encounter has played out, there’s usually an option for the players to either follow the creatures to where they are going, or to follow their trail to where they came from. This is a fantastic opportunity to introduce new sites to the sandbox. People probably have noticed that the numbers of creatures encountered in the wilderness often goes into the dozens, and in the case of some lairs even in the hundreds. These numbers are not for a group of four PCs being suddenly ambushed by an entire army on the march. These are numbers for populating keeps, camps, and lairs. These groups are what you find when you follow the wandering groups of monsters back to their homes. And they don’t have to be hostile. The same reaction rolls for random encounters in dungeons can be used when approaching a stronghold in the wilderness. Which I think has the potential as an amazing tool to create a wilderness area that is a living space where players can discover the unexpected and the GM has fantastic opportunities for very freeform and improvisational play.

As I mentioned, a campaign like this also needs tools. The following are mechanics that I’ve already dabbled with to make running such adventures easier. Some of which overlap with the changes to the basic game mechanics mentioned in the previous section. Most of these are things that the Expert rules already cover, but I feel they are clunky and inconvenient to use. All of it can be done better without dramatically changing the outcomes.

- Item-based encumbrance.

- Simple rules for water and food rations.

- Mechanical consequences for lack of food and water.

- Rules for disease(?)

- More robust rules for hunting and foraging.

- Travel speeds that map exactly to 6-mile hexes with no half hexes or third hexes traveled per day.

- Simple rules for river travel speed.

- Rules for tracking.

- Wilderness exploration turns analogous to Dungeon exploration turns.

- Stronghold and lair generator tables.

Aumaril

The final piece for my upcoming campaign during which all these ideas for new rules and mechanics will be playtested is the setting. I like the sound of Aumaril, and I checked that it isn’t already used by something else. And it’s different enough from Arduin and Amalur to not seem like a knockoff.

Aumaril is a world dominated by severe weather and many volcanoes. Volcanic activity covers the sky in ash every few decades that can cause brutal winters and ruin harvests, but on some occasions have tipped the climate to a point of causing ice ages that can range from centuries to tens of thousands of years. The world only emerged from four thousand years of winter fairly recently, which destroyed the civilization of the fey, reduced the kingdoms of the giants to barbarism, and diminished the empires of the serpentmen to a shadow of their former greatness. As the ice retreated and forest returned to the northern lands, mortal barbarians migrated from the south to make them their home. In recent generations, these first mortal empires have fallen into chaos and decay, and many people are fleeing deeper into the wilderness to try their luck among the abandoned ruins of the fey and giants, and things much more older than even the ancients.

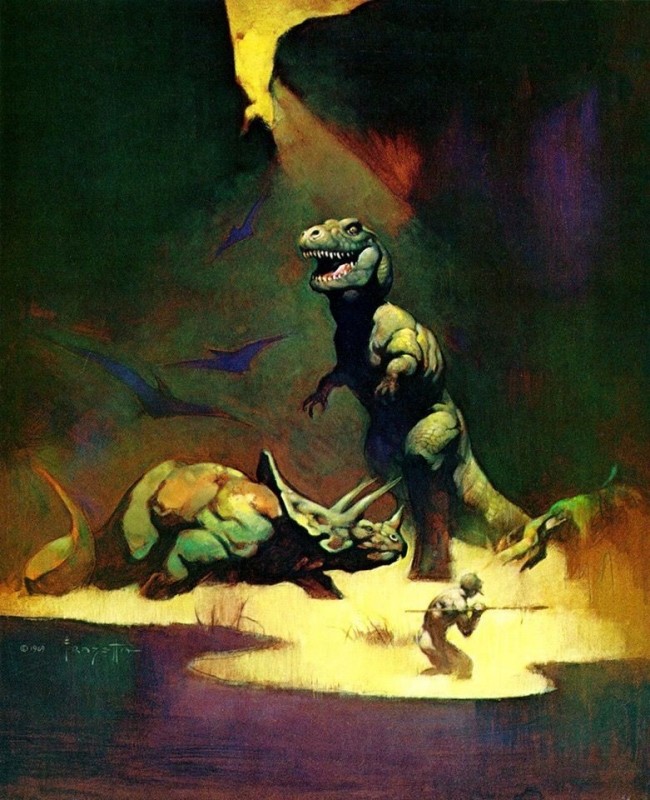

While civilization is centered around three old empires that have seen much better days, and could be interesting places for adventures in their own right, these are not the actual setting where the planned campaign takes place. The adventures of the PCs cover the vast wilderness of forests and mountains that still cover most of the world and remain largely unexplored, but have many ancient ruins from the previous age and civilizations that have long since disappeared. I am an unashamed fan of the 70s and 80s Sword & Sorcery style that gratuitously blends together traditional medieval fantasy elements with weird and alien environments from science fiction or prehistoric Earth. Mushroom forests, dinosaurs, and giant insects are totally my jam, as are evil sorcerers in giant black towers covered in skulls. Which I think has never been executed better (at least stylistically) than in Morrowind. I’m not leaning as much towards the camp or melodramatic, but I still think this is a really cool aesthetic that can be just as well suited for more down to earth fantasy adventures.

One thing that really excites me about this setting is that it’s being populated by various intelligent creatures that have been created for D&D pretty long times ago, but never really seen much breakout success or prominent appearances. In addition to the very human-like Aumarilians, who are greatly inspired by various cultures from the Hyborean Age and the Elder Scrolls, the other major peoples are chitines, derro, fey’ri, grimlocks, locathah, quaggoths, raptorans, and stone giants. Goliaths seem to have become quite popular in 5th edition, and of course yuan-ti have always been famous.

This part of my great creation probably won’t see any kind of proper release as some kind of book, but I guess I’m probably going to share various bits and pieces about it here as the actual campaign develops.

The defeat of the Naga and conquest of the South by the God-King marked the beginning of mortal civilization and the rise of the first kingdom. But though the serpents were driven back beyond the great river, their threat to the mortal realms was never completely broken. It is by the might of the God-King and his royal guard that the southern realms are being kept safe and their people are protected from being enslaved or devoured.

The defeat of the Naga and conquest of the South by the God-King marked the beginning of mortal civilization and the rise of the first kingdom. But though the serpents were driven back beyond the great river, their threat to the mortal realms was never completely broken. It is by the might of the God-King and his royal guard that the southern realms are being kept safe and their people are protected from being enslaved or devoured.

After several thousands of years, the age of ice and snow came to an end, with the glaciers retreating and the barren rubble slowly turning into new forests. As life returned to the northern lands, so expanded the reach of the serpentmen, who claimed much of them for their ascending empire. For over 2,000 years the serpentmen empire span across the lands on both sides of the sea, but even their time eventually came to an end.

After several thousands of years, the age of ice and snow came to an end, with the glaciers retreating and the barren rubble slowly turning into new forests. As life returned to the northern lands, so expanded the reach of the serpentmen, who claimed much of them for their ascending empire. For over 2,000 years the serpentmen empire span across the lands on both sides of the sea, but even their time eventually came to an end. Though the empire of the serpentmen had survived the rivals that had driven them from the northern provinces, they had lost much of the great power they onces possessed. So when new barbaric peoples appear on their borders, led by four powerful sorcerers who had united the tribes under them, the serpents stood little chance to resist them, though the wars of conquest ranged for many decades. The invaders conquered all of the great Grasslands and much of the coastal lands north of the sea, driving the empire from the north.

Though the empire of the serpentmen had survived the rivals that had driven them from the northern provinces, they had lost much of the great power they onces possessed. So when new barbaric peoples appear on their borders, led by four powerful sorcerers who had united the tribes under them, the serpents stood little chance to resist them, though the wars of conquest ranged for many decades. The invaders conquered all of the great Grasslands and much of the coastal lands north of the sea, driving the empire from the north. With the hated serpents now no longer on their borders, the sorcerer lords turned towards securing their own hold over the lands they had conquered, and soon came to be elevated to be worshiped as living god kings. They also became each others greatest enemies, competing over the most valuable farm and graze lands along the large rivers that run through the great valley of the Grasslands.

With the hated serpents now no longer on their borders, the sorcerer lords turned towards securing their own hold over the lands they had conquered, and soon came to be elevated to be worshiped as living god kings. They also became each others greatest enemies, competing over the most valuable farm and graze lands along the large rivers that run through the great valley of the Grasslands.