This week I finished my D&D 5th edition campaign that I’ve been running almost weekly over nearly five months for a total of 19 games. This has not only been the longest campaign I’ve been involved with, but also the first one that actually reached its conclusion. I think it’s also the best one I’ve ever run by a considerable margin. My experiences from running campaigns on and of over the many years since the 3rd edition was first released, but also the many theories about gamemastering that I’ve learned about in the seven years since I started this site finally came together in a way that made me feel like I actually knew what I was doing, and that things turned out more or less as I had intended. And in the process, I think I learned even more from this campaign than any other I’ve ran in the past.

So all taken together, this really was a huge success.

But one important thing I realized in the final third or so of the campaign is that D&D really is not the game for me. I feel like I am done with Dungeons & Dragons, but also with dungeons, as well as dragons.

One of the reasons is the particular style of fantasy that D&D is both build upon and it perpetuates through the mechanics of its rules. D&D fantasy is fantasy that does its primary worldbuilding through establishing mechanics and standards for how things work and how beings behave. It’s a form of fantasy that is structural and rational, with clear rules that everyone can understand, leading to expectations that players automatically bring to the game. It is the opposite of being magical, wondrous, and elusive, which to me defeats the overall purpose of fantsy. Everything becomes systemised, quantified, stiff, and bland. I do have some fond memories of The North of the Forgotten Realms, and think there’s some really cool sounding ideas about the less popular lands in the distant east. Dark Sun looks really cool with really great concepts, and there’s something unique and compelling about Planescape. But when you play campaigns in these settings, you’ll always be playing D&D, and players looking at everything through the D&D lense, trying to analyze their situation and formulate their plans by D&D logic.

While I think that the D&D mindset is not my cup of tea and that other styles of fantasy are much better, this is something that I could live with and accept as something that comes with entertaining the players. As a GM, my job is not to get the players to play the ideal fantasy campaign that I would want to play, but to give them the opportunity to play the way they want to play. (There is only darkness and despair down the path of telling the players how to play the campaign right.)

The bigger problem, and I think ultimately the dealbreaker, is that D&D is build around certain structures that I simply don’t find compatible with where my strength in the preparation and running of adventures lie. I just don’t get dungeons.

And it’s not like D&D needs dungeons because they are in the title of the game and players would be disappointed if they don’t get them. The whole game is based around dungeons on the most fundamental level. The game needs dungeons, not just as locations within the story but as a structure in gameplay. D&D is a game of attrition. If the party is facing just one villain, even one surrounded by guards and minions, the fight will either be very short, or very lethal for the PC. Single fights are not meant to be difficuly, they are meant to gnaw away on the endurance of the party. To play the game as it is designed to work, you need environments where the players will be facing six, eight, or ten fights in a row. And that is just not something that works in the kind of stories that I can create. For situations that make sense to me and that I feel will be rewarding for players, it almost never makes sense to have more than two or perhaps three encounters before leaving the place to regroup for the next outing on another day. When I make larger dungeons, they always end up as huge piles of guard creatures that serve little narrative function. Classical dungeons also regularly have puzzles, but I almost never find situations in which the presence of a puzzle would make sense and wouldn’t be nonsensical. You also can have nonhostile NPCs and creatures, and I often include those, but they don’t contribute to the attrition that games like D&D need. I often feel like I do rationally understand how dungeons are supposed to work, how they are structured, filled with content, and the purpose they have in a game. I just find them somewhat dull and completely out of place in the kind of adventures that I know how to make compelling and fun.

So what then about simply forgetting about all that attrition stuff and embracing the unlimited freedom to make the way whatever I want it to be. Yes, that certainly is an option. But what would really be the point of that? The main thing that broke the camel’s back for me with 3rd edition was the abundance of new class features and special abilities that characters get at almost all levels. And that’s something that is still present in 5th editon. Not quite as heavily as in 3rd, but still very much. Way too much, I think.

D&D is ultimately a game about pursuing experience to get access to new abilities. At least in the editions of the last 20 years, but it’s been like that for spellcasters since the very beginning. D&D is a game about getting new special abilities. It’s a main element of what drives players forward, and the prospect of new abilities is what makes players pick their character concepts. The group I had for my last campaign was amazing. They all went all in, head first, with all the narrative freeform nonsense I presented to them. But even these players were constantly talking about the new abilities they were looking forward to after and between games, and they were always proud to tell each other what cool new tricks they just got when they reached a new level. This is something that is baked into the game. This is what the game is about. And I feel that when you run adventures for the group in which most situations don’t result in fighting, then what is the point of running D&D? I am feeling very confident that I am certainly able to run cool and fun adventures. But when I run D&D, I have to provide plenty of opportunities for the players to use their wide and always increasing range of cool special abilities, and I simply don’t see how to do that in adventures that are cool and fun.

Dungeons & Dragons is not for me. If a group of players I like to play with invites me to a game of D&D, I probably wouldn’t say no. As long as I don’t have to come up with adventures that provide something to be entertaining for the players, I have no problem with it, even when I think other games would be even more fun. But running D&D sets requirements and limitations for the GM that don’t work with my abilities as a GM and what I consider enjoyable about gamemastering. Perhaps if the planets happen to align and some unexpected circumstances arise, I might possibly run a B/X campaign or something of a similar type. They are nowhere near as burdened by special abilities, but in the end they are still games about large dungeons filled with monsters and puzzles. I much more see my future with heroic fantasy games looking like Barbarians of Lemuria. Or perhaps some Apocalypse World. But for now it’s Star Wars all the way. And not the Star Wars with the D&D class features, or the Star Wars with the funky dice. The original Star Wars d6 game, where all the dice you need are d6s, and all your character’s abilities are the basic skill rolls. Rules light rules at their best.

But today I was seeing a trailer for the new From Software game

But today I was seeing a trailer for the new From Software game  I think the first thing that stands out are the boss monsters. They are not simply just boss fights. With some exceptions like the Capra Demon, most of the prominent ones are unique beings with a specific backstory and context. And equally important, they have powers that make them stand apart from other monsters and a very different kind of threat. When you take our own everyday world as your frame of reference, then a minotaur, centaur, or satyr would be an amazingly strange creature and great threat. But when you are already in a fantasy world, then even a minotaur doesn’t have anything supernatural or divine about it.

I think the first thing that stands out are the boss monsters. They are not simply just boss fights. With some exceptions like the Capra Demon, most of the prominent ones are unique beings with a specific backstory and context. And equally important, they have powers that make them stand apart from other monsters and a very different kind of threat. When you take our own everyday world as your frame of reference, then a minotaur, centaur, or satyr would be an amazingly strange creature and great threat. But when you are already in a fantasy world, then even a minotaur doesn’t have anything supernatural or divine about it.

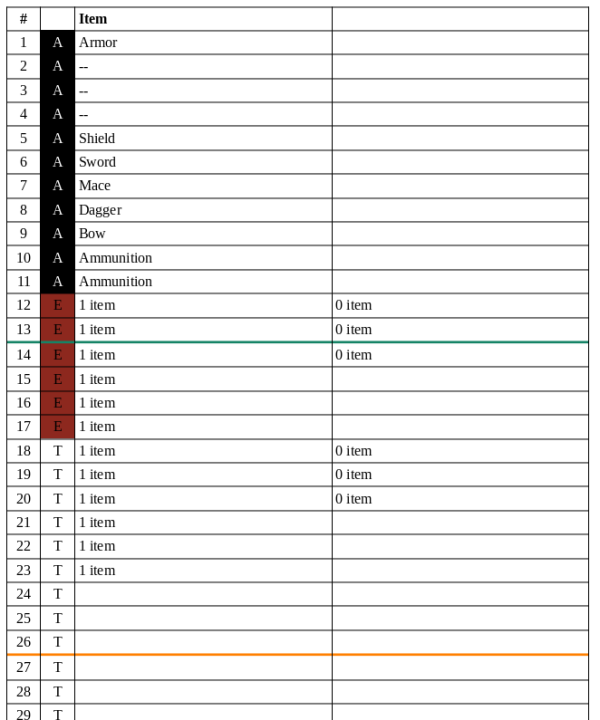

Encumbrance in D&D has always ranged from bad to terrible. The idea behind encumbrance is actually great. The default assumption for the first decade or so had been that the party enters a dangerous place, gets their hands on valuable stuff, and gets back out again, preferably with their loot and without anyone dying. When wandering monsters are a thing (look forward to part 3) and fighting battles is a negligible source of XP (look forward to part 4), then getting in and out quickly is of the essence. The longer it takes you, the greater is the risk of anyone dying with no benefit in trade. So as you keep delving deeper into the dark unknown, you are using up some of the tools and supplies you have brought with you, but at the same time get weighted down by the treasures you find. Which leaves you with two choices. Slow down and risk fighting more opponents and reducing your odds of being able to run away. Or reduce your weight, either by choosing to leave some of the treasure you’ve found behind, or by dropping some of the equipment that you hopefully won’t be needing on your way back to the surface. Hang on to all your potentially life saving tools and weapons as you slowly crawl back to the exit, or make a mad dash to safety? Or play it safe and leave some of your hard fought for rewards behind? This is a real question that players will have to face. There is no right answer which two out of these three you should choose and will greatly depend on the constantly changing situations. To me, this is one of the big things that make exploration adventures so exciting.

Encumbrance in D&D has always ranged from bad to terrible. The idea behind encumbrance is actually great. The default assumption for the first decade or so had been that the party enters a dangerous place, gets their hands on valuable stuff, and gets back out again, preferably with their loot and without anyone dying. When wandering monsters are a thing (look forward to part 3) and fighting battles is a negligible source of XP (look forward to part 4), then getting in and out quickly is of the essence. The longer it takes you, the greater is the risk of anyone dying with no benefit in trade. So as you keep delving deeper into the dark unknown, you are using up some of the tools and supplies you have brought with you, but at the same time get weighted down by the treasures you find. Which leaves you with two choices. Slow down and risk fighting more opponents and reducing your odds of being able to run away. Or reduce your weight, either by choosing to leave some of the treasure you’ve found behind, or by dropping some of the equipment that you hopefully won’t be needing on your way back to the surface. Hang on to all your potentially life saving tools and weapons as you slowly crawl back to the exit, or make a mad dash to safety? Or play it safe and leave some of your hard fought for rewards behind? This is a real question that players will have to face. There is no right answer which two out of these three you should choose and will greatly depend on the constantly changing situations. To me, this is one of the big things that make exploration adventures so exciting.