Formulating my thoughts on a subject always helps my putting my ideas into focus. And so after writing yesterday about the challenges of using a pointcrawl map for a large dungeon I came up with some new ideas for how this problem might be solved.

Pointcrawling really is all about navigation by landmarks or travel along marked paths. During overland travel this is usually the only way there is to pick where you are going. This makes is very easy to take a hex map and convert it into a point map by simply removing all the hexes that don’t have keyed sites or encounters or lie along a path that connects two of the keyed locations. And you can easily convert a point map back into a hexmap by simply overlaying a hex grid on the chart of sites and paths.

But with dungeons this is not the same. As people discovered very early on in the history of RPGs, dungeons are very different environments from outdoor landscapes. In a dungeon you don’t chose your path or destination, you can simply go forwards and backwards in a corridor and pick from a fixed number of other corridors at junctions. When you want to go dungeon crawling with a point map, you can’t just take any grid map dungeon and convert it to a point map. This doesn’t work and you only end up with nonsense that has the same complexity as you started with. Instead, you have to design the entire dungeon from the ground up with a point map in mind.

A dungeon that would be very easy to do with a point map is a ruined castle with an open courtyard. In fact, Chris Kutalik’s ruincrawl is really an attempt to explore cities, not buildings. With an open castle, you can have the first area be the gatehouse that has one entrance and one exit. Once the players reach the exit of this area they can overlook the courtyard and see the various buildings that make up the interior. There may be a keep, a chapple, stables, a tavern, a warehouse, an inner gatehouse, and lots of uninteresting small sheds. The sheds and the patrol corridors in the walls have nothing interesting in them so they can be ignored and are not getting mapped. The other buildings each get their own small map and are marked on the point map as distinct areas. From their position at the exit of the outer gatehouse the players have a clear path to the stables, warehouse, tavern, and inner gatehouse, and if they go through the inner gatehouse they can also walk over to the chapple and the keep. What the paths in the courtyards look like is irrelevant. That’s a basic and simple pointcrawl.

This doesn’t work in a dungeon that is entirely underground, though. Simply because you can’t see other areas from a distance. You can’t say “let’s go over there” when you can’t see “there” and don’t even know that “there” exists. Ina grid map dungeon this is not a problem since you simply follow the corridors and then see where they lead to. With navigation by landmark being out of the picture, following marked paths is the only remaining option. But the whole point of pointcrawling a dungeon is that you want to strip out all the empty halls and chambers that make up the majority of the place and only have the players interact with the most interesting areas. I think the solution to this conundrum is to design dungeons for a pointcrawl along a network of highways. Coridors that clearly stand out from the rest and serve as main connective routes between major prominent area of the dungeon. Dozens or hundreds of minor side passages branch off from these leading to living quarter and storerooms, but they are not included in the map and can not be actively explored by the players. To look at a part of the dungeon in detail there has to be something that visible stands out and draws the attention of the PCs to the fact that there might be something worth looking at.

This is of course a few steps removed from the complete hands off approach you can have with grid map dungeons where the GM really only tells the players what they see and what happens as consequence of their actions. By designing a dungeon like this the GM takes the previlege to tell the players that their characters are not interested into exploring certain corridors and rooms and that they simply continue on their exploration along the provided path, which might not sit completely well with everyone. But really, this is exactly what outdoor pointcrawls do too. It’s an aknowledging nod towards the fact that games are abstractions of adventures and not accurate simulations. It takes away player choice, but really only choices that the GM knows in advance to be completely irrelevant. I don’t think many players would feel sorry about not having to explore 80 empty rooms in a room before they find a room that has something in it. When you look at fiiction this happens all the time. If you take a book or movie at face value, characters are instantly teleporting around all the time between scenes. But everyone is in agreement that the characters did walk between locations and that they probably talked during that time and perhaps even had some encounters that are completely inconsequential to the story. This is the underlying idea here.

A secondary issue I had been pondering is how to indicate the border of an area when each area consists of multiple rooms and is surrounded on all sides by more or less indentically looking rooms. What I think might be the best approach is to construct the whole dungeon not as one continous cluser of rooms but instead as multiple self-contained cells, which each cells having only two or three exits that lead to other cells. This is one of the things that makes it necessary to design a dungeon as a pointcrawl from the ground up. Grid map dungeons usually don’t have such clear cell structure and a great number of possible connections between thematically linked areas.

A system of self contained grid mapped cells connected by highways running through otherwise nondiscript cells is my solution to having huge dungeons that don’t involve long stretches of tedious searching through empty rooms or being implausibly cramme with treasures and monsters. Or at least my current attempt at a solution.

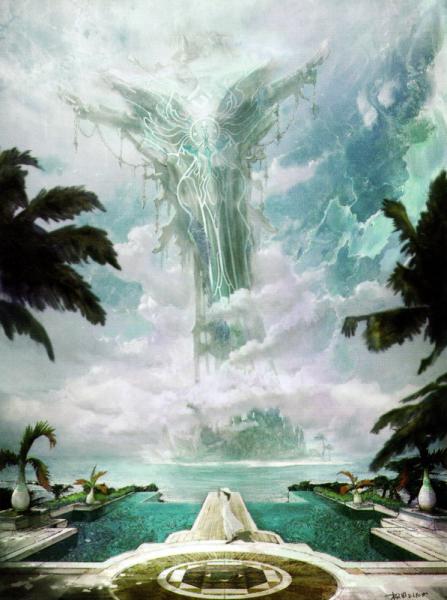

Tower Builders

Tower Builders

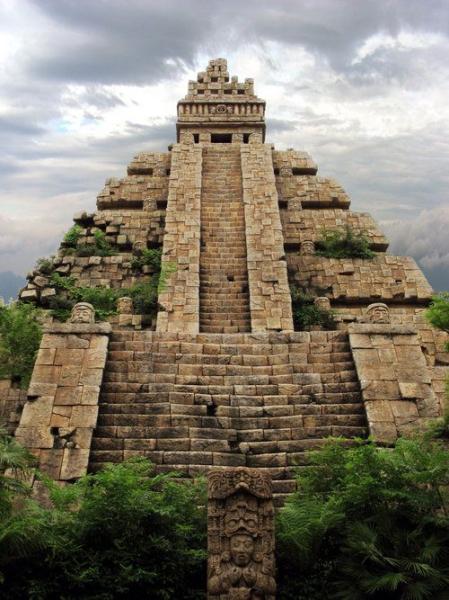

Rock Carvers

Rock Carvers

Tree Weavers

Tree Weavers

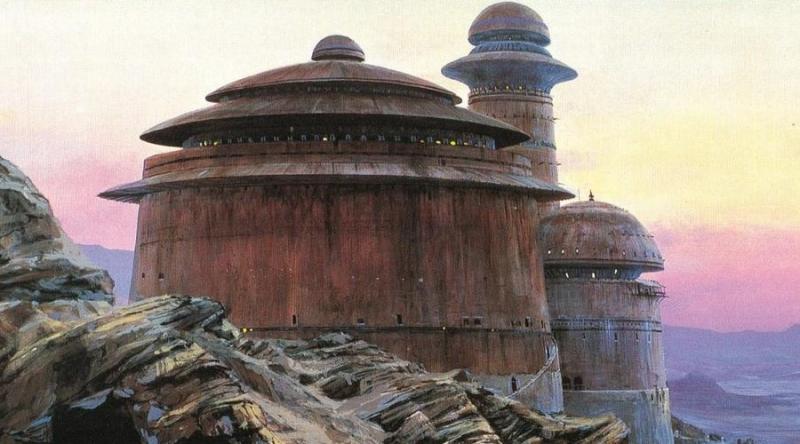

Glass Makers

Glass Makers