I’ve long had an ambivalent relationship with hex maps. I think the conventional approach to hexcrawl campaigns in which the party enters a 6-mile hex and discovers whatever cave or ruin in located inside just goes beyond any believable plausibility. As an “outdoor dungeon room”, 6-mile hexes are just way too big and even 1-mile hexes would be stupidly huge. But I really do like hex maps as a tool to quickly and easily estimate the length of a winding path through the wilderness and around natural obstacles like mountains or large lakes. I really can’t imagine the Woodland Vales system without using a hex map for the GM. I think the players should never actually see a hex map, as cartographers of a typical fantasy world would not be able to create any maps with that degree of accuracy regarding relative directions and distances. Navigation should be done by the players entirely by following roads, rivers, and visible landmarks. But for a GM, hexes are a great tool to track supply consumption and random encounter frequencies.

People have long discussed the merits of different hex scales for adventure and campaign maps, and I’m entirely in the 6-mile hex camp for long-distance overland travel. But for doing multiple criss-crossing trips through a much more bounded play area, this might not necessarily be the best scale as well. But to choose the right scale for a hex map, it’s first necessary to establish what kind of information is actually meant to go on that map.

The Default Domain Template

For my Kaendor setting, I recently made the decision to model borderland settlements on the image that is being created by the D&D Expert and Companion rules by Frank Mentzer from 1983. A region of wilderness that is dotted by small keeps of independent lords surrounded by a small area of farmland with numerous tiny villages paying taxes for the lord’s protection against the monsters of the wilds. Mostly as an aesthetic choice. I just find it very evocative. Having a bit of casual research into the medieval manor system for social and economic organization in western Europe, I came up with the following average template for what such a lord’s domain might plausible look like.

At the center of the domain is the lord’s keep. A fortified residence that serves as the domain’s military headquarter and treasury, that might also serve as a refuge for people living nearby in times of attack. Close by or surrounding the keep is a town where most of the domain’s businesses and services are located. The rest of the domain would consists of several manors. These are the lands that are under the economic control of other wealthy and powerful families of the domain. Either as personal property or on rent from the lord. These manor estates in turn would work a small part of that land but rent out most of it to common tenant farmers. The masters of these manors make up the retainers of the lord of the domain. Depending on the local culture, these might be called knights or something to a similar effect. Part of the agreement with the lord that grants them the right to own or rent property in the domain is to provide military service. In addition to themselves and perhaps some of their sons, these retainers would each also employ a few semi-professional soldiers as their men at arms, funded by the rent the retainers receive from their tenants.

A plausible scale for the numbers of the people making up such a generic domain I settled on the following, which I believe falls into roughly the same range that you find quoted for some actual medieval baronies and manors.

A domain has one keep that is home to the lord. The keep is next to the domain’s single main town of 1,000 to 2,000 people. The rest of the domain consists of 20 to 30 manors that provide the lord with 1 retainer and 5 or 6 men at arms each and have a further population of 200 to 300 farmers. This comes out as a total population of 20-30 retainers, 100 to 180 men at arms, 1,000 to 2,000 townspeople and 4,000-9,000 villagers. That’s a bit low for the ratio of villagers per townspeople, but ultimately this is about getting a sense of scale rather than doing precise head counts.

As a very broad generalization, it appears that it takes about 3 acres of fields and pastures to support one person. For our roughly 10,000 inhabitants of an average domain, this comes out as 120 km². Assuming that the domains are pretty wild borderlands and between 1/3 and 1/2 of the land is unworked by farmers, this would be 160 to 240 km² for the total domain size. This translates to about 4 to 6 6-mile hexes, 20 to 25 2-mile hexes, or 80 to 100 1-mile hexes.

The Why and Where of Towns

In a pre-modern farming society, farms are largely self-sufficient, producing all the food they consume and most of their clothing. However, once you get to have carts with wheels, horses with harness, and plows with metal blades, and you want to do some embroidery on your good clothes with fine threads in bright colors, you can’t do all these things by yourself on your farm and require the work of experiences specialists with specialized tools. And while there might be one guy who has a simple forge and can make crude nails in most farming villages, for many of these specialized trades you can have a single business supplying a very large number of customers over a fairly large area. And you need all these customers to make your business economically viable.

Leaving the farm to go on an errand to one of these specialists takes time and keeps you away from your own work. So farmers will always prefer to go to a place that has many businesses and services in one spot so they can do multiple errands on a single trip. When given the choice, they will do their errands in whichever place has the most businesses close together. Businesses located in these places will do better than those in the middle of nowhere, and so all businesses will naturally move to a single central place. That’s a town.

But while farmers will always prefer to do all their errands on one trip to the largest town, this does have a limit. Even more preferable than doing everything in a single trip is to make all your trips in a single day and be back home before nightfall. Staying the night in a foreign town is unappealing and expense, and getting stuck on some dark road until the next morning is even worse. Also, many farmers might not like to have their family be alone on the farm for the whole night, and somebody is having to feed the animals in the morning. So even when a larger town is available in the area, it’s typically beaten out by smaller towns that can be visited on a single day trip. And as it turns out, the maximum distance for a trip to town, doing your errands, and making it back home by nightfall is about 5 to 6 miles when traveling on foot or with a horse cart. This means that every town is surrounded by a bubble some 10 to 12 miles across from which it gets all its customers. If there’s another town inside that bubble, the one that has the better range of services will draw in all the customers and businesses in the smaller town will have to move to stay competitive. If there are rural villages that are located outside of any of these bubbles, then there’s a huge business opportunity for trades people to set up shop there and provide their goods without competition and a new town will grow. Once an area has been newly settled by farmers, businesses will move around and potential towns grow and decline until the entire area is covered in permanent towns whose bubbles of customers are just touching, but also leave very few gaps between them. And we can see that in many rural places. The distances between towns are rarely much shorter or much longer than that.

The Options for Hex Scales

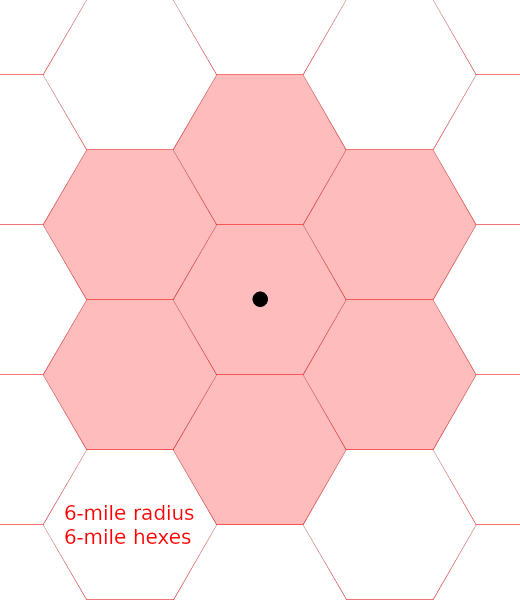

As I mentioned earlier, I am quite the fan of 6-mile hexes. It’s the most commonly used scale for hex maps and its resolution is quite convenient for long distance overland travel. But when it comes to mapping a domain consisting of four to six hexes, maybe not so much.

At the scale of a domain, this hex size really doesn’t provide anything useful. All you could mark on this is that any sites in the domain are either right next to the town or six miles away. And if the domain takes up five or six of the seven hexes, every domain will have nearly identical outlines on the map. This really doesn’t look fun.

At the scale of a domain, this hex size really doesn’t provide anything useful. All you could mark on this is that any sites in the domain are either right next to the town or six miles away. And if the domain takes up five or six of the seven hexes, every domain will have nearly identical outlines on the map. This really doesn’t look fun.

Now the 6-mile hexes could be split into 3-mile hexes, but that just looks really wonky when trying to overlay a 3-mile hex grid over a 6-mile grid. So let’s go right ahead to look at 2-mile hexes instead.

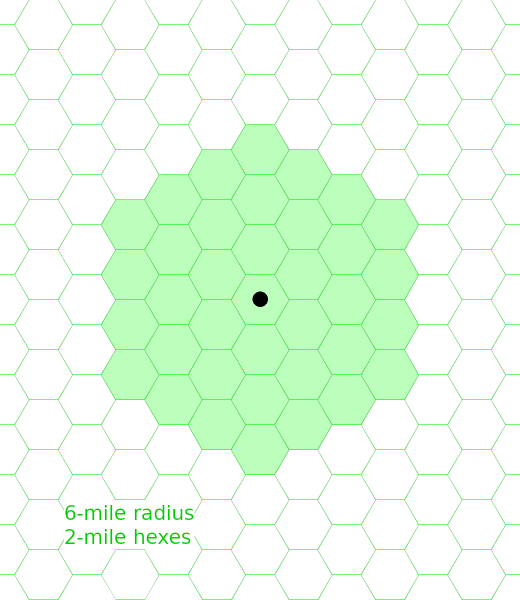

I say that’s more like it. We have 37 hexes within a 6-mile radius around the central town, and would require some 20 to 25 of those to make up the territory inhabited by the domain’s farming population. That’s vastly more options for domains of different shapes. It’s also a resolution in which the relative positions of various villages or landmarks in the domain could be indicated by a single hex coordinate.

I say that’s more like it. We have 37 hexes within a 6-mile radius around the central town, and would require some 20 to 25 of those to make up the territory inhabited by the domain’s farming population. That’s vastly more options for domains of different shapes. It’s also a resolution in which the relative positions of various villages or landmarks in the domain could be indicated by a single hex coordinate.

Just for the sake of completeness, let’s take a look at 1-mile hexes, which has been advocated for small scale wilderness exploration by early D&D.

If your entire campaign takes place only in a single 6-mile hex and the directly neighboring wilderness hexes, then I can see using a 1-mile hex overlay being a decent choice. But for Woodland Vales, I also want to include interactions between different lords and the overland journeys between domains. If you were to make a map with 8 domains and some wilderness between them and surrounding them, I think going down to a 1-mile hex resolution seems like overkill.

If your entire campaign takes place only in a single 6-mile hex and the directly neighboring wilderness hexes, then I can see using a 1-mile hex overlay being a decent choice. But for Woodland Vales, I also want to include interactions between different lords and the overland journeys between domains. If you were to make a map with 8 domains and some wilderness between them and surrounding them, I think going down to a 1-mile hex resolution seems like overkill.

The 2-mile hex seems like the ideal hex size for my intentions with the Woodland Vales borderland exploration system.